|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 16

|

|

Wednesday, April 18, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 16

|

|

Wednesday, April 18, 2007

|

LICHTENSTEIN'S BRUSHSTROKE: Roy Lichtenstein began his series of Brushstroke paintings in 1965. In the early 1980s, the brushstrokes became three-dimensional like this one in oil on patinated bronze (1996). This "amiable, oddly animate, and genially self-contained" work can be seen in "Pop Art: Contemporary Perspectives," which will be at the Princeton University Art Museum through August 12. Hours are Tuesday–Saturday, 10 a.m.–5 p.m.; Sunday 1–5 p.m. Closed Monday and major holidays. Admission free. Visitor information is available at (609) 258-3788. Both the photo and quote are from the exhibit's multi-author monograph. |

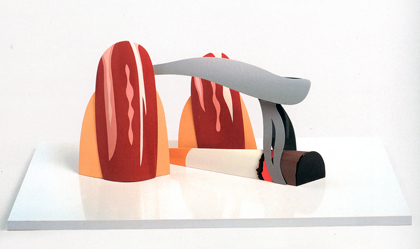

SMOKER STUDY SCULPTURE: Imagine it on a Times Square rooftop circa 1965 advertising cigarettes. This alkyd on steel creation by Tom Wesselmann is on view from now through August 12 in the Princeton University Art Museum's "Pop Art: Contemporary Perspectives," which is also the title of the monograph from which this image is taken. |

“Where the poet does his job by virtue of an effort of the mind he is in rapport with the painter, who does his job with respect to the problems of form and color.”

“Everything modern or possibly merely new … is uncompromising.”

—Wallace Stevens, from a 1951 talk at the Museum of Modern Art

If you could fill an art gallery with works based on the imagery of Wallace Stevens, who had a painter’s eye for form and color, you’d have a show for the ages. As I read around in this forever-modern and most painterly of poets, I keep finding lines that could be captions or subjects for the artists represented in the new Pop Art exhibit at the Princeton University Art Museum. It’s tempting to imagine what Robert Indiana or Roy Lichtenstein could do with Stevens’s “Fat cat, red tongue, green mind, white milk” or his old sailor who “catches tigers in red weather.”

“Pop Art: Contemporary Perspectives” (also the title of the multi-author monograph published by the museum and distributed by Yale University Press) begins with a Lichtenstein screenprint of a disembodied hand pointing right at you the way the famous World War I poster of Uncle Sam pointed at would-be recruits: Pop Art Wants You. The question was, did I want Pop Art? I was not in a receptive mood. My sinuses were raw after a week-long cold, my head was heavy with the misery of the Sunday New York Times, it was a gloomy afternoon, and all the coat hangers in the lobby had been taken, thanks to a well-attended special video presentation that delayed access to the center of the show for some 15 minutes. As I circled the one available gallery, I was thinking, “How can I write about this? What can be said?” I saw nothing that jolted or exceeded my expectations; no visual equivalent of jazz’s “sound of surprise.” There were some nice pieces by Robert Indiana and Jasper Johns, and it was easy to like Allan D’Arcangelo’s big-as-life Side View Mirror that evoked the pre-digital Playland Penny Arcade America where you could steer your little car, trying to keep up with the painted roadway as it rolled right and left through a shifting landscape. At the Lambertville Flea Market the previous day I’d seen material for a dozen Pop Art exhibits about 20th Century America; all the left-overs from the great American consumer banquet, and its popular culture sideshow, were laid out on tables or displayed indoors in stalls. I might have found more to enjoy in the flea market overtones in Jasper Johns’s Decoy II with its Ballantine cans and in the hanging tools on painted blue sky sections in Jim Dine’s Art of Painting No. 2, if I hadn’t been distracted by the situation. A museum aide was doing her best to politely hold back patrons who were understandably impatient to see the rest of the show.

Perhaps the forced delay contributed to my sense that the first gallery had been “arranged” while the second one simply happened. It’s refreshing when art comes suddenly, boldly at you as if you’d collided with it on the street. The sensation sends you back to the time when you could be thrilled by the idea of a ring that glows in the dark being concealed in a cereal box. You don’t have to ask yourself “How do I write about this?” You don’t have to make notes. All of a sudden the shiny forms on the wall are doing wonderful things with the light, radiant primary colors gleaming on a landscape painted on porcelain while an enormous red dream of a table radio looms the way such things did when you were a kid and were high half the time and didn’t know it.

The artist who brought this show to life for me is Tom Wesselmann, whose work had extra impact because I didn’t know it. With Warhol and the others, I knew what was coming. This painter was also paying homage to other artists, like Mondrian, who inspired the tilework on the wall behind the big red radio, and Matisse, who provided some of the patterns from which Wesselmann sewed and cut and molded his still-lifes and landscapes. Looking at his Smoker Study Sculpture of a female hand with bright red gleaming fingernails holding a cigarette, I thought of the rooftop creations Wesselmann, Warhol, and Lichtenstein might have made if they’d been turned loose on Times Square, the crossroads of consumer culture and commercial art.

Warhol’s Show

David Bowie wrote his song, “Andy Warhol” (“Looks a Scream/Hang him on my Wall”), back in the 1970s, and Warhol’s Brillo box and Campbells Soup can were so familiar, so much of the period, that I gave his work here only a cursory glance, with the exception of a piece from The Thermoflax Series. The image surrounding a handwritten poem by Gerard Malanga ( The poet wrestles with language ) could be a snapshot of one of the daily acts of violence occuring in one of those safe-as-Indiana Baghdad neighborhoods.

It’s all too easy to take Warhol for granted, as I did on my way through the exhibit. Ric Burns’s documentary (available on DVD at the Princeton Public Library) should be seen by anyone who makes that mistake. His is surely one of the great American stories. The other Pop artists, some of whom were “there” before him, only worked the genre. Warhol lived it, orchestrated it, and disseminated it. He died 20 years ago this February. Think what he could be doing now, with innovations like YouTube and all the bright new tools that would be available to him. Of course he’s everywhere anyway, most recently in a new movie, Factory Girl, about Edie Sedgwick, who starred and died in the ongoing show Bowie was singing about (“I’d like to be a gallery/Put you all in my show”).

Brushstrokes

“Abstract sculptors, like abstract painters, should be totally abstract, not half so,” according to Wallace Stevens, who also had a special fondness for Picasso’s statement that “a picture is a horde of destructions” and liked to quote it in relation to poetry. I’m not sure how he would respond to Warhol, but it seems more than likely that he’d relate to what Roy Lichtenstein was doing with his Brushstroke series, particularly Brushstroke (1996), a small standing sculpture done in oil on patinated bronze. Having imagined what Lichtenstein would do with a line of Stevens, think of the poem (“Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Brushstroke”) Stevens might write about this stylish magnification of the painter’s line, the painted word, the abstracted heartbeat of art. As Kevin Hatch points out in his essay on Lichtenstein in the monograph, the piece is “amiable, oddly animate, and genially self-contained.”

Enter Mrs. Stevens

Art and commerce came together brazenly enough when Andy Warhol was struggling for a way to establish himself as the CEO of Pop in 1962. According to Ric Burns’s film, someone told him, “You like money. You should paint pictures of money,” and so he accomplished one of his breakthrough works with a wall of dollar bills while making a statement about the realities of the profession. I wonder if Warhol ever heard of the way poetry, art, and commerce came together four decades earlier for Mr. and Mrs. Wallace Stevens. When they were living on West 21st Street in Manhattan, their landlord was the sculptor who designed the dime and half-dollar issued by the

U.S. Treasury Department in 1916, and his model for the head used on what came to be known as the Mercury dime was Stevens’s wife, Elsie. If you grew up between 1916 and 1950, that was Elsie Stevens’s face on the head side of the ten-cent coin you were buying your comics and Cokes with, at least until FDR became the face on the almighty dime. Warhol would have loved it.