| NEWS |

| |

| FEATURES |

| ENTERTAINMENT |

| COLUMNS |

| CONTACT US |

| HOW TO SUBMIT |

| BACK ISSUES |

James Joyce's City of Words: A Book Big Enough to Live In

Stuart Mitchner

My review of Firestone Library's Lost Generation exhibit featuring Princeton native Sylvia Beach and her Paris bookshop Shakespeare and Company (Town Topics, March 16) neglected to mention her most significant contribution to literature. When James Joyce despaired of finding a publisher for Ulysses, it was Sylvia Beach who came to the rescue. Describing how he "immediately and joyfully" accepted her offer to bring out the book, she admits thinking it "rash of him to entrust his great Ulysses to such a funny little publisher." The imposingly beautiful first copy of the landmark work of literature produced by the "funny little publisher" is the central feature of a landmark exhibition at the National Library in Dublin that coincides with the ongoing celebration of the 100th anniversary of the day on which Ulysses took place, June 16, 1904. It was a day the author had good reason to immortalize. On June 16, 1904, he met his wife-to-be, Nora, who once told Sylvia Beach she hadn't read a page of "that book." Ms. Beach goes on to suggest that it was "quite unnecessary for Nora to read Ulysses" since she was "the source of its inspiration" and Joyce's marriage to her was "one of the best pieces of luck that ever befell him."

Sylvia Beach makes those observations in her autobiography, Shakespeare and Company, which she begins by telling us that her father was for seventeen years "pastor of the First Presbyterian Church in Princeton, New Jersey." Thanks to George D. Cody's letter in a recent issue of Town Topics, we now also know that Sylvia not only came of age in Princeton ("with its trees and birds ... more a leafy, flowery park than a town") but is buried in Princeton cemetery.

Besides pointing out Princeton's link to what was one of the previous century's most remarkable literary events, my object is to give an account of the celebration of the book and its author that I saw firsthand a few weeks ago in Dublin. When you walk into the world of Ulysses that has been brilliantly and daringly recreated in the new gallery space at the National Library, the first thing that attracts your attention is a replica of the front of Sylvia Beach's bookshop. Among the literary treasures displayed in the window, by far the most impressive is "Copy No. 1" of Ulysses, inscribed by Joyce to his patron and friend Harriet Shaw Weaver, who had hoped to publish the book herself and who provided an infusion of money at a point when both author and publisher were perilously short. Ms. Beach had to make a special effort to get this same first copy to Joyce, as promised, on his birthday, February 2, 1922. When the printer, located some distance away in Dijon, said it would be impossible, she persisted until she received a telegram telling her to meet the 7 a.m express from Dijon, which she did, her heart "going like the locomotive" as the train "came slowly to a standstill and I saw the conductor getting off, holding a parcel and looking around for someone – me. In a few minutes, I was ringing the doorbell at the Joyces' and handing them Copy No. 1 of Ulysses."

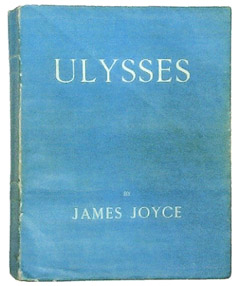

Subsequent editions, no matter how handsomely done, are no match for the magnificent, massive copy ("iconic," in the curator's words) with its Greek blue wrappers; a few, lesser copies of the first edition, unsigned by the author, are going for as much as $75,000 on the net. Although the actual book is behind glass, exhibitgoers can have the experience of looking through it (or even turning it over) by using a touch screen to turn digital pages; they can also magnify sections of the text. The same digital magic is available for those who want to look through some of the working notebooks Joyce used for various episodes; not only can you turn the pages but you can magnify the author's handwriting (a trick the harried printers in Dijon would have been grateful for); you can even undo his deletions by digitally lifting away the orange crayon marks with which he crossed out doubtful lines and passages. In every such display I've visited in the past, the best you could hope for was to peer down into a glass-topped display table at some selected page of manuscript; here you can seemingly sift through the pages for yourself.

What makes this exhibit so extraordinary is that it's not merely celebrating the book but attempting to assemble a complex of forces equivalent to its essence, the life of it, its ambience, its music and movement. While other museums may achieve settings worthy of their subjects, I know of nothing comparable to what the National Library has accomplished. The act of imagination that is Ulysses has been expanding, developing, and replenishing itself ever since people started reading it and living in it, and so it lives here, its potency reflected in the atmosphere of sounds, images, and voices haunting the National Library, which the author himself frequented as a student. In fact, the ninth episode of Ulysses takes place in the librarian's office behind the Reading Room counter. In that chapter Joyce's alter ego, Stephen Dedalus, expounds his theories about Shakespeare's personal investment in Hamlet – another example of a work living beyond its time and place, to be wondered at and theorized over through the ages, as Ulysses has been and will be.

A singer with a fine tenor voice, Joyce was as alive to music as he was to language, which is why Ulysses sings as often as it speaks. Songs and sounds being so crucial to the book, it's no surprise that the curators have evoked the musical life of Dublin circa 1904 with a display of posters advertising musical productions with Joycean connections. The posters themselves are musical, thanks to a sound system in the walls that can be activated by stepping on switches hidden in the floor boards. But the Ulysses exhibition goes beyond this sort of routine period accompaniment, plunging into the heart of the book in the form of what the exhibit guide calls "a constantly evolving montage of sounds related to and inspired by" home life with Leopold and Molly Bloom at No. 7 Eccles Street. Domestic articles are also on display, including Bloom's bar of lemon soap, which is no less real than the wadded up papers littering the floor of a replica of the author's own domestic base where certain of Nora's undergarments are strewn about much in the way Molly Bloom's are in the fictional bedroom she shares with Bloom. Peeking into this amusingly messy and apparently true-to-life glimpse of the chaotic surroundings Joyce worked in, you begin to wonder if he was any more or less real than his creation. After all, the day being so elaborately commemorated here is Bloomsday, not Joyceday.

You don't have to read Ulysses to feel that when you walk the streets of Dublin you are walking around in Joyce's imagination. All you need to do is spend an hour exploring the National Library exhibition. It's a rare work that can suggest a reality so inviting to imagine that people want to believe in it. If pressed, some readers may admit that no such person as Leopold Bloom ever actually walked these streets, but in their literary heart of hearts, they think he did. The only comparable instance of this phenomenon might be readers of Sherlock Holmes who want to believe that such a person lived and worked in London and resided at 221B Baker Street. Bloom lived at 7 Eccles Street. Did he really? Of course not, but that didn't stop the Joyce Center on Great George Street from removing the actual door at No. 7 and installing it at the Center, where none of the real-life articles used by the living author have the impact of that door. Such is the power of Ulysses: that the doorway presumed to have been opened and closed by a fictional being should excite the imagination more than objects actually associated with the author who created that character.

Reading the Book

What a thought; to presume to review Ulysses. What could a reviewer say to the so-called common reader? Do you have to be a devoted student of literature to take it on? Can all those tourists who walk out of the exhibit smiling and stimulated pick it up and even begin to understand, after an hour's reading, what all the excitement was about? Perhaps it's enough simply to scan the immensity of the work, the way you might look down from a safe vantage point onto some labyrinthine bazaar you'd never have the courage to explore, at least not without an armed guide. My advice would be to remind yourself that all bets are off with Ulysses. Forget notions of plot, suspense, beginning, middle, and end. Forget it's a book. Think of it as – well, a city. Does anyone expect you to swallow a city in one gulp? If you were reading Manhattan would you start at the Battery and plod uptown, street by street? When you go to New York, you may spend all your time below 23rd Street. People talk about their favorite neighborhoods. Lovers of Ulysses have their favorite passages and episodes. It's unlikely that even the most intrepid Joycean has read every word of it. If it's your first visit to Joyce's imagination, you won't find it hard going until you get to the Proteus episode, which is teeming with the allusions and philosophical fancies Stephen indulges in as he walks along the beach. So why not jump ahead to Leopold Bloom's morning rituals and his cat. You'll love the cat. But if you skip Proteus, you miss one of the best descriptions ever written of a dog being a dog. It belongs in the hall of fame of canine literature – and it was written by a man who was deathly afraid of dogs.

All one can say, finally, is that it's a book big enough to live in and walk around in and get lost in. Something that can be said of few books. And a Princetonian helped bring this one into the world.

The 100th anniversary Bloomsday celebration is still going on. You can still visit the Ulysses exhibition. It's open until autumn 2005 and it's free. If you go to Dublin this summer, don't miss it.