|

|

Vol. LXV, No. 16

|

Wednesday, April 20, 2011

|

Working hard at it over a period of years, Schwitters succeeded in completely ‘Merzing’ the house where he lived. The soaring Merz-columns ingeniously constructed out of rusty old iron bars, mirrors, wheels, family portraits, bedsprings, newspapers, cement, paints, plaster, and glue — lots and lots of glue — forced their way upward through successive holes, gullies, abysses, and fissures.Hans Arp

The full-sized, walk-in centerpiece of the Princeton University Art Museum’s must-see exhibit, “Kurt Schwitters: Color and Collage,” is a replica of a room in the Merzbau, the multi-faceted structure Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948) called “the work of my life.” (See page 23.) This “composition without boundaries” is both playful and sinister, bright and haunted, combining the twisted charm of a Hobbit hideaway with an expressionistic moodiness and whitewashed-Greek-island clarity, Caligari’s Cabinet in Myconos. The reconstruction was completed in 1983 by Peter Bissegger, a Swiss stage designer, who followed photos of the original taken 50 years earlier by Wilhelm Redemann and reproduced in the exhibit catalogue, each one bearing the parenthetical note “destroyed 1943.”

Online you can see a U.S. Army photograph of the Allied bombing of Hannover that took place on October 8, 1943. It’s an ugly, unreal image, the shadows and stark semblances of the falling bombs like the work of a malevolent grafitti artist armed with a thick black marker. In the sprawling urban complex below, the areas of maximum impact give off a white glare. RAF reports claim that 504 planes took part, of which 27 were shot down: “Conditions over Hannover were clear and the Pathfinders were finally able to mark the centre of the city accurately; a most concentrated attack followed.”

Somewhere in the fiery ruins was the building at Waldhausenstrasse 5 in which Schwitters had housed the work of his life, a personal labyrinth few people were ever allowed to see. Forced to flee Nazi Germany for Norway in 1937 (and Norway for England when the Germans invaded in 1940), he had to leave his magnum opus behind, in the care of his wife, Helma, who survived the bombing only to die of cancer a year later.

Refuge in England

When he learned of the attack, Schwitters was living in England, in the Lake District town of Ambleside. After building a version of the Merzbau in Norway that had been lost in a fire caused by children playing with matches, he began working on a Merz Barn in England, although a stroke suffered in 1944 slowed him down. According to the chronology in the exhibit monograph, he was also writing poetry in English, “having renounced the German language during the war.” Thus does “barn” join the German word he adopted for the name of his art, his one-man movement, taken from kommerz (commerce) and freely applied to his other works, as the notes for collages throughout the exhibit illustrate (Merzbild, Merzmosaik, Merzmappe, Kubistisch Merz).

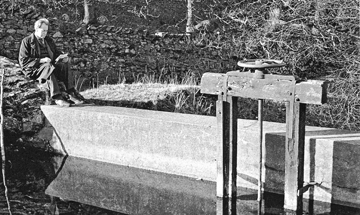

A photograph taken by his son Ernst shows Schwitters sitting, reading, on the sunlit bank of a Lake District stream. The scene has a haunting serenity. Here he is, the displaced artist, musing in the idyllic refuge he found in the country whose bombers razed his city and his home, and destroyed his Merzbau. The photo can be found in the catalogue and would be a worthy addition to the exhibit; but then so would the photograph of the bombing of Hannover. Given his ties to the stricken city, Schwitters might have found the image disturbing, fascinating, perhaps even useful, if you can imagine the master of color and collage attacking it with his art. He could daub a patch of deep blue sky over the incendiary glare, affix a page torn from a ration book, add the label from a packet of tea (as in the Ty-P-Hoo Tea collage from 1944 shown here), and top it off with an dark blue upside-down postage stamp showing King George in profile (as in the work from 1947 he titled poco poco). Or maybe that would have been too obvious, too simplistic a notion for so subtle and elusive an artist — to be embellishing the grim scene with bits and pieces of English ephemera like a play on English agents of destruction.

There’s a weirdly prophetic image of the air attack in Schwitters’s poem about the building of the Merzbau, where “Lines of force cut the air.” In a 1936 letter to MoMA’s Alfred Barr, he describes the interior in similarly contact-driven terms: “The suggestive impact of the sculpture is based on the fact that people themselves cross these imaginary planes as they go into the sculpture. It is the dynamic of the impact that is especially important to me.”

Looking Inside

A rare first-hand account of the Merzbau from around the same mid-1930s time period can be found in Richard Hülsenbeck’s Memoirs of Dada Drummer. After depicting Schwitters’s poem, “To Anna Blum,” as a “typical product of an idealism made dainty by madness,” he recalls a visit to the residence at Waldhausenstrasse 5:

“Schwitters showed us his workroom, which contained a tower. The tower tree or house had apertures, concavities, and hollows in which Schwitters said he kept souvenirs, photos, birth dates, and other respectable and less respectable data. The room was a mixture of hopeless disarray and meticulous accuracy. You could see incipient collages, wooden sculptures, pictures of stone and plaster. Books, whose pages rustled in time to our steps, were lying about. Materials of all kinds, rags, limestone, cuff links, logs of all sizes, newspaper clippings.”

The “less respectable data” may refer to the death mask of the artist’s infant son, or the Kathedrale des erotishen Elends (Cathedral of Erotic Misery), which, in a poem with the same title, Schwitters says “was the name/I gave the disorder of my studio./I saw it as a sculpture to build and balance/then finish and place in a gallery.” According to Gwendolen Webster’s essay on the Merzbau in the exhibit catalogue, Schwitters’s creation had to be concealed from the public eye, his efforts to publicize the work having come “at the worst possible time,” following Hitler’s election victory when “the deteriorating political and social climate was hardly conducive to promoting a groundbreaking work that defied all that the regime stood for.” Meanwhile Schwitters was being “vilified in National Socialist publications” and his work was being subjected to inclusion in exhibitions of “degenerate art.” Since he had “every reason to fear the consequences if the Merzbau came to official notice, he became ever more cautious about making its existence known,” and of the few who were permitted to see it, most were “either close friends or visitors from abroad.”

In addition to the anarchy synonymous with the Dada movement Schwitters was associated with until he became persona non grata, the essence of his work suggests the collecting and redeeming for art of refuse, litter, clutter, trash, everything antithetical to the Nazi ideal. According to a broadsheet displayed in the exhibit, “Dada stirs everything up. Dada knows everything. Dada spits on everything,” just as Dada, or its high priests, eventually spat on Schwitters by burning his “infamous” poem “Anna Blume” in effigy.

The Poet

In “Color and Collage,” the discarded bits of merz-related ephemera in the collages (ausmerzen means “to discard”) offer clues to when and where they were composed. In the pre-1937 works the various stubs, labels, fragments of letters and such are in German; between 1937 and 1940 they’re in Norwegian, while the post-1940 versions are in English.

For all the grim nuances in the grottos of the Merzbau and some of the darker wartime pieces, the ambiance of Schwittzers’s collages, especially the work done in England, is bright and upbeat. The man we see sitting in the Ambleside sunshine in 1945 is a poet capable of playful paraphrases of Wordsworth (“I wander lonely as a clown”). In the poem, “How My Life Has Changed,” he writes of receiving a telegram in London, his wife dead from cancer, his “Hannover home struck by bombs./Helma, my best friend for life/along with my life’s work, both gone.” Then, after “the V2s, and my stroke,” he’s nursed back to health by “the neighbour girl” who “holds a cup of tea” to his lips. ‘Want tea?’” she says, and smiles./She can’t see what is empty inside me/Yet day by day she fills it.” The girl’s name is Edith Thomas, but he, ever the poet-collagist, calls her Wantee, and she goes with him to the Lake Country.

In a poem titled “To Ambleside 1945,” composed around the time of the sunny moment in the photograph, Schwitters writes, “for once again peace has won/the atom’s smashed and now/there are four Germanies/equal to less than one/and nothing at all to go back to.”

A year later, however, he’s still hopeful, as in a poem addressed to a friend in Hannover, “But really, the Merzbau, is there nothing left?” Wondering, “If I came back, might I not sift through the ruins/like an old archaeologist? salvage fragments/to sell to Americans? rebuild it room by room/from the rubble of the house?”

“Kurt Schwitters: Color and Collage,” will be at the Princeton University Art Museum through June 26. Kurt Schwitter’s poetry can be found online at http://capa.conncoll.edu/morton.merzbook.html#2.