|

|

Vol. LXV, No. 17

|

Wednesday, April 27, 2011

|

|

|

A translated poem is necessarily a new thing, but it has a relationship with the original. Or, as I’m beginning to think more and more, both have a relationship with some text of which each, original and translation, is a manifestation.Paul Muldoon (2004)

“Don’t come back here please without a poem that’s going to change my life.”

Paul Muldoon likes to give these instructions at the end of a class, according to an online University feature about “the wildly creative” poetry program at Princeton and this weekend’s two-day Princeton Poetry Festival at Richardson Auditorium. As the festival’s founding director and chairman of the Lewis Center of the Arts, Muldoon will introduce the first group of readings at 2 p.m. on Friday, April 29, thus ending National Poetry Month not “with a whimper” but “a bang.”

Understood, that Muldoon is making a point about the magnitude of the poet’s task when he gives his students that daunting assignment. So is Ralph Waldo Emerson when he claims that what “makes a poem” is “a thought so passionate and alive, that, like the spirit of a place or an animal, it has an architecture of its own, and adorns nature with a new thing.” It’s hard to imagine a more driven and unsparing statement of the cause than Emerson’s 1844 essay, “The Poet.” The sage of Concord, who died on this date, April 27,1882, goes so far as to declare, “The people fancy they hate poetry, and they are all poets and mystics.” Given the level of public discourse these days, there must be a few million notable exceptions to this stirring piece of wishful thinking. Fortunately, poetry surprises politics every now and then.

Poetry in Life

Poetry happened in Tucson this past January at the memorial service for the victims of the shooting that killed six people and gravely wounded Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords. It happened when President Obama departed from his prepared remarks to tell the world “Gabby opened her eyes.” What made the moment special was the casual spontaneity with which the president relayed the news, calling Giffords “Gabby” as if the woman fighting for her life were everyone’s close friend. It helped that his manner was familiar, informal, felt but not forced, and so understated that he sounded almost matter-of-fact when he said “Gabby opened her eyes for the first time,” repeating it in full, twice, his voice lifted each time in tandem with the cheering, applauding audience before he said it once more, simply, quietly, as if savoring every word, “Gabby opened her eyes.” The president’s thoughtful paraphrase of the scene at the hospital, which in fact had taken place after he paid his own visit, may not have changed anyone’s life, but it gave a huge charge of positive energy to the event.

Poetry and Paraphrase

The word “paraphrase” took on new meaning for me recently when I began exploring the music and life of Franz Liszt, who made it his mission, among many, to absorb works by other composers — songs by Schubert, arias from Verdi — and render them in his own style. With his paraphrases, Liszt was spreading the musical wealth, like a Johnny Appleseed of melody.

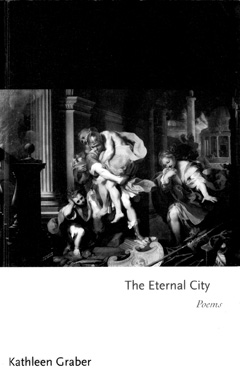

In her collection The Eternal City (Princeton University Press 2010), festival poet Kathleen Graber, who will be reading at 2 p.m. on April 29, is accompanied by Freud, William James, St. Augustine, Jim Jarmusch, William Blake, Johnny Depp, Bellini, Werner Herzog, Caruso, Un Chien Andalou, Kant, Christ, Caravaggio, Marcus Aurelius,Christopher Wren, Reservoir Dogs, Milan Kundera, Walter Benjamin, and Peggy Lee, among others. Graber translates the image of Klaus Kinski’s face in Herzog’s film Fitzcarraldo into a line to remember (“that the brain is the opera house of the mind”) while jungle drums are answered by “the imperfectly captured voice of Caruso” coming from Fitzcarraldo’s gramophone. Graber’s “Dead Man” channels Jim Jarmusch’s 1995 western of the same name, which in turn spreads the wealth of William Blake through a half-Blackfoot Indian who intones passages from “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell” to the doomed Cleveland accountant who happens to share Blake’s full name. The poem’s paraphrase of the film surrounds the poet’s personal reality — a newborn nephew, the “roar of the vacuum” that stops his crying

— and makes possible, as happened with Fitzcarraldo, some of the poem’s most memorable images (“the inky band fanning across the morning blue/of a kestrel’s tail feathers,” the moment “part of some migration. Every snow bunting composes its own song,/& a careful watcher can tell one kittiwake from its neighbor by the little dots on the tip of its wings”).

One sure way Graber’s “Dead Man” will change lives is by sending those who read it off to see one of the best films of the 1990s.

Born in Translation

“Even when I’m not writing I’m a poet,” Israeli poet and Poetry Festival participant Agi Mishol said in 2002 when asked by her translator Lisa Katz if, as “a teacher, a farmer, a mother,” she thought of herself as a poet first. In a sense, the Hungarian-born Mishol’s life as a poet has been a translation into Hebrew. Asked by Katz whether or not knowing Hungarian “in any way” interfered with her Hebrew, Mishol replied, “Hebrew is my home, I’m completely at home in Hebrew.”

Having challenged his poetry students to change his life, Paul Muldoon would surely appreciate the way Mishol accomplishes the reverse in “Geese,” a poem that begins with reference to a math teacher who, in effect, changed her life by telling her that her “head was good only for hats,/and that a bird with brains like mine/would fly backwards.” Sent to “tend the geese,” she decides years later that he was right, because nothing makes her happier than to watch her “three beautiful geese … falling upon bread crumbs,/joyful tails wagging.” In the last stanza she transforms the terms of the math teacher’s dismissal into poetry:

Since then my math teacher has died,

together with the math problems

I could never solve.

I like hats

and always at evening

when the birds return to the tree

I look for the one flying backwards.

“Something Beyond Oneself”

Brazilian poet Paolo Henriques Britto, who will be a panelist and reader at the festival along with his translator Idra Novey, could be describing the challenges of both poetry and translation in “On High” when he writes, “Not only you, poet, suffer from/the stingy work of demiurges./Even the gods write twisted lines,” and goes on to question his own translation of those lines: “Still, one has to attempt. For instance:/’Night is a deep backpack.’ No, not backpack. Maybe bat cave?”

Britto’s “twisted lines” of the gods waiting to be translated or paraphrased or simply discovered call to mind Paul Muldoon’s idea, quoted at the top, that the source of both the original and translation may be come from a “text of which each … is a manifestation.” In the same Spring 2004 Paris Review interview, Muldoon goes on to suggest that writing poetry involves “the experience of recognizing that one is not in command,” that “basically one has given oneself over to something beyond oneself. In this case, the language.”

Charles Simic, another featured Princeton Festival poet, ends his latest collection, Master of Disguises (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 2010) with a poem he calls “And Who Are You, Sir?”

I’m just a shuffling old man,

Ventriloquizing

For a god

Who hasn’t spoke to me once.

The one with the eyes of a goat

Grazing alone

On some high mountain meadow

In the long summer dusk.

———

Fifty years after Emerson’s death, on the same date, this date, April 27, homeward bound on a ship from Mexico, the American poet Hart Crane, 33, took his own life by jumping overboard. He left behind a wake of epigraphs, not least the last line of “At Melville’s Tomb” — “This fabulous shadow only the sea keeps.”

For more information about the Princeton Poetry Festival, which takes place Friday, April 29, and Saturday, April 30, visit www.princeton.edu/arts/poetry festival.