|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 18

|

|

Wednesday, April 30, 2008

|

|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 18

|

|

Wednesday, April 30, 2008

|

|

Besides being National Poetry Month, April is also Jazz Appreciation Month, and, on top of that, 2008 marks the 50th anniversary of one of the seminal Beat Generation works. Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s Coney Island of the Mind contains seven poems “conceived specifically for jazz accompaniment,” two of which were recorded with Kenneth Rexroth and the Cellar Jazz Quintet on Fantasy LP No. 7002.

Driving to Poetry

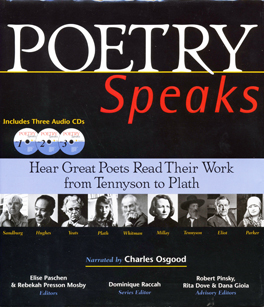

While it may be a stretch to compare spoken poetry to jazz, the two terms have enjoyed a semantic partnership ever since the days when poetry readings accompanied by jazz were a feature of the club and coffee house scene associated with the Beat movement. To be honest, my memory of the small taste of that combination I had years ago in the Village isn’t positive. But I found real music in the voices of poets reading in Poetry Speaks (published in 2001 by Sourcebooks, Inc.), a handsome, hefty volume of texts and readings that comes with three CDs spanning the centuries, from Tennyson to Plath.

After beginning a recent drive into the city with the first of the three Poetry Speaks CDs playing, I soon found that I’d rather be driving to the long, flowing solos of that poet of the tenor sax, Wardell Gray. There are better turnpike transitions than going from Robert Frost reciting “The Road Not Taken” to the WINS bridge and tunnel traffic alert. After meeting up with a friend in Manhattan, I found a parking spot near St. Mark’s Place, where we spent more parking meter time than we’d intended listening to poets read poetry. After some barely audible but exciting recitations by Tennyson, Browning, and Whitman, W.B. Yeats came through loud and clear. His spoken introduction to “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” is worth the price of the package. It’s usually instructive to read a poet’s written account of a poem’s genesis, but hearing the poet describe it in his own voice is a rare treat. “I wrote the poem in London when I was about twenty-three,” Yeats recalls. “One day in the Strand I heard a little tinkle of water and saw in a shop window a little jet of water balancing a ball on top. It was an advertisement [for] a cooling drink but it set me thinking of Sligo and lake water.” Besides clearing up an “obscurity” (“When I speak of noon as a ‘purple glow’ I must have meant by that a reflection of heather in the water”), he announces somewhat testily his determination to read the poem “with great emphasis on the rhythm”: “It gave me a devil of a lot of trouble to get into verse the poems I’m going to read,” he says, “and that is why I will not read them as if they were prose.” At this point the voice you’ve been listening to may resemble that of the elder statesman the young James Joyce once supposedly told to his face, “You do not talk like a poet, you talk like a man of letters.” Well, when Yeats gets to the poem, he sounds like a poet and then some, compelling our attention with an eerie vibrato such as the Ancient Mariner himself might have used to transfix the Wedding Guest in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner.”

When Ezra Pound reads on the same CD, he sounds even more “like a poet,” so much so that you may suspect that he and Yeats learned from the same singing master, except that in “Cantico Del Sole,” Pound takes it to antic, acrobatic extremes when he disassembles a simple sentence and creates a masterful travesty of deranged syntax, his target the philistine wasteland he calls America. His inspiration was a judge’s ruling that obscenity in the classics was acceptable in America because the audience was so small, therefore: “The thought of what America would be like/If the Classics had a wide circulation/Troubles my sleep.” Pound’s set of variations on the same line (he goes up, he goes down, he goes all around that “wide circulation”) is not unlike what Thelonius Monk does when he chops a familiar melodic line into playful segments and serves up something you never heard before.

Into Stevens

The first three poems read by Wallace Stevens sound pretty much like standard poet-in-the-lecture-hall stuff. “Not Ideas About the Thing But the Thing Itself,” however, is a voyage to a poet’s interior. It’s as if he had a microphone in his larynx and you’re in there too. The singing of Yeats and Pound seemed to come from some remote dream world of poetry, the words like wind-blown distant music. When Stevens reads as he does here, remoteness has nothing to do with it; there’s no distance at all between you and the words; you seem to be inside the language; he’s swallowed you whole. When he ruminates on the “sound in his mind,” you and it are the same thing. For the minute and a half it takes him to say what he has to say, it’s as if you’ve become the poem. None of the other poets in this collection (at least among those I’ve heard) achieve quite this degree of intimacy. To be able to feel this close to a poet who is generally thought to be distant and difficult (the buttoned-up insurance executive with his body in a Hartford office and his head in the heavens) is one of the many pleasures offered by Poetry Speaks, which belongs in every library in the country.

Missing Ginsberg

Lawrence Ferlinghetti is quoted on the back cover of an early edition of Coney Island of the Mind to the effect that “the printing press has made poetry so silent that we’ve forgotten the power of poetry as oral messages. The sound of the streetsinger and the Salvation Army speaker is not to be scorned.” While he doesn’t read in Poetry Speaks, you could say that Ferlinghetti’s represented by Allen Ginsberg, the poet he published in the first volume of the City Lights Pocket Poets series. Certainly if anyone caught the spirit of the sound Ferlinghetti’s talking about it was Ginsberg, who reads from Howl on the third CD. We could use him now; we need a bardic provocateur goading the establishment with word jazz the way Ginsberg did when he stood up to Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, the FBI, Vietnam, and the military industrial complex. With the country struggling to survive the violations and degradations of the Bush years, imagine having Ginsberg on hand to chant mantras at Bill O’Reilly or drown out Chris Mathews and the talking heads with his harmonium. Instead of the heavy-handed likes of Michael Moore, imagine having a buoyant poet/streetsinger like Ginsberg taking up the cause. Watching him singlehandedly charm a crowded theatre or park or stadium was poetry and music all in one.

Rackett

Poetry and music? How could I forget? This is Princeton, home to Rackett, where Paul Muldoon’s lyrics meet rock and roll and the old poetry to jazz combination is updated and amplified into another realm. Rackett’s next gig is May 7 at the Cake Shop, 152 Ludlow Street in New York.