|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 32

|

|

Wednesday, August 11, 2010

|

“What we play is life.”Louis Armstrong

For the past week I’ve been celebrating Louis Armstrong’s birthday, August 4, 1901, by listening to the breakthrough Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings from 1926-1928. Meanwhile, the fact that the first African American president was born on the same day exactly 60 years later has me fantasizing that some cunning White House advisor marked the moment by filling Obama’s ears with the power and glory of his birthday mate’s playing on “West End Blues” and “Tight Like This.” As a result, so goes my fantasy, the mystically endowed president will power and glory his way through the current maze of crises with speeches whose fanfares and cadenzas will galvanize the nation at a time when America 2010 is beginning to feel like a cacophonous throwback to America 1970.

An Unhappy Parade

On May 4, 1970, Nixon and Kissinger having launched the invasion of Cambodia, the country was shaken by the shootings at Kent State (four students dead), and ten days later, at Jackson State (nine students dead). The national mood had been grim enough before those events. According to the prevailing view, young and old were profoundly estranged, so much so that “generation gap” seemed a laughable euphemism; it was more gaping wound than gap.

In that season of our discontent, the refrain coming from FM stations and car radios around the country was “This summer I hear the drumming/Four dead in Oh-i-o,” from “Ohio,” the song Neil Young composed only days after the shootings and rushed to record with Crosby, Stills, and Nash.

On Sunday, May 24, after a friend’s marriage was solemnized at Kirkpatrick Chapel up on the Old Queens campus at Rutgers, the scene outside was a microcosm of the state of the nation. In the aftermath of an event that was all about union, the wedding party stood divided into two distinct groups, young and old, freaks and straights, warily eyeing one another across an invisible battle line. While grimly tolerating the bearded groom and his mane of shoulder-length blonde hair for the sake of the occasion, various relatives of the newlyweds were staring daggers at the bearded best man with his monstrous Afro, the African American maid of honor, and the motley assembly of shaggy graduate student types like myself. We were a poster-ready image of the enemy.

While we stood looking down the hill toward Somerset Street and the railroad embankment abutting the New Brunswick station, we heard the sound of brass and drums (“This summer I hear the drumming”) as an American Legion parade came marching up George Street, flags flying, and began passing directly in front of us. It was not a happy, celebratory sort of parade, not with the marchers combatively chanting “U.S.A. All the Way” and other patriotic slogans, but even so, it seemed for a moment that the deep-seated American nostalgia aroused by the spectacle, the sound of drumbeats and brass, might cut through the chill, disperse some of the tension, maybe even inspire a shared smile between young and old. Not a chance, for no sooner had the marchers passed from view than two college students appeared running in the opposite direction, running, clearly, for their lives, with a posse of legionnaires, arms churning, in pursuit. The students had attempted to join the march and were now being tackled, pummeled, and beaten right before our eyes, one of them yelling “But we’re Americans, too!” Obviously the attempt by the young to join such a march had been perceived as an aggressive act, a piece of unAmerican mockery. Once we fathomed what was going on, the younger members of the wedding party, including the best man, the newlyweds, and the maid of honor, charged down the hill to break it up. Seeing a freshly married bride and groom descending on them, the legionnaires backed off and hurried to rejoin the march.

The Cry

What makes Neil Young’s “Ohio” so effective isn’t the timing or the “Four Dead” mantra alone; it’s Young’s searing vocal. In the liner notes to his 1977 album, Decade, he wrote, “It’s still hard to believe I had to write this song. It’s ironic that I capitalized on the death of these American students. Probably the most important lesson ever learned at an American place of learning.” David Crosby thought that Young’s insistence on keeping Nixon’s name in the line “Tin soldiers and Nixon coming,” was “the bravest thing” he “ever heard.” More interesting than that is the next line, “We’re finally on our own,” which seems to suggest that the killings had somehow released into the brawling world a whole prodigal generation.

Jazz critic Michael Zwerin, who died this past April, used “the Cry” as a term to describe the sound of tenor saxophonist Wardell Gray: “A direct audial objectification of the soul. You know it when you hear it.” Perhaps more than any singer of the time, Young had the “Cry” in his voice.

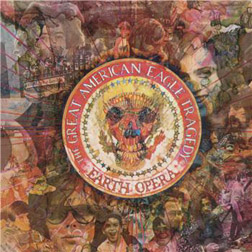

Earth Opera

Two years before Kent State, when the Cry was not about Nixon’s Cambodia but Lyndon Johnson’s Vietnam, it could be heard loud and clear in the voice of Peter Rowan. Then the lead singer of a Boston-area folk rock group called Earth Opera, Rowan wrote and performed, unforgettably, an ambitious anti-war anthem from 1968 called “The American Eagle Tragedy.” Before that, Rowan had turned the country’s hatred of counterculture youth into music in “The Red Sox are Winning,” whose closing lines — “And the weather is strange, no summer this year/In the days of the war/But the Red Sox are winning” — are followed by the roar of a crowd that sounds like Fenway Park filled to capacity with one voice howling again and again, “Kill the Hippies!” In “Home of the Brave,” another song from Earth Opera’s self-titled 1967 debut album, Rowan channels Noel Coward and cabaret (“But the war was grand/A lovely parade”) to give a sarcastic twist to his message (“My home the grave, my land is free”), the essence of which is no less relevant in 2010: “People all around me/They can’t understand/How I lost my hand.” Rowan’s outraged conclusion, with his near hysterical repetition of the line, “And I know it’s paid for/Yes very well paid for,” over the sound of a demented march, makes the Doors’ Jim Morrison’s “Unknown Soldier” sound fake and formulaic.

“Stop the War!”

After several listenings to Earth Opera’s first album, one of the stand-outs of the period, I found Peter Rowan’s number in the Boston phone book and called him up. As we talked about the music, the cover art, and the lyrics (he mentioned a fondness for Samuel Beckett), he told me that the group would be playing on the Cambridge Common the following weekend. He advised me to be sure not to miss it: “We’re doing something special.” He was referring to “The American Eagle Tragedy,” which many heard for the first time that Sunday afternoon. The excitement engendered by the ten-minute-plus epic was phenomenal, so rare was it to hear a passionate message driven by passionate music. It was the Cry again, but this was beyond politics and protest; this emotional whirlwind thrilled you through, shook you, and left you reeling. Beginning with a full-scale overture of saxophone harmonics from two tenors and an alto, the mood moved from quiet and ominous, with the saxes blowing rich and deep, then shrill and harsh as the bass and drums came pounding, tom-toms alone, then snare, then Rowan coming on full-throated to deliver the chorus, “Call out the border guard,/the kingdom is crumbling/The King is in the counting house/laughing and stumbling/His armies are extended way beyond the shore/As he sends our lovely boys to die in a foreign jungle war.” After the opening cry, each repetition of the chorus following three relatively placid verses (the Queen in the garden moaning and weeping, the orchestra assembling and trying “in vain to tune,” the huntsman shooting the silver arrow that slays the eagle) is more intense than the one before, until at the end Rowan simply cuts loose, carried by wailing saxes and pounding drums, the pace frenzied, relentless, headlong, as he chants, howls, and screams, from “I can’t stand it any more” to “why-why-why-why-die-die-die-oh no, oh no, oh no,” to screams of “Stop the war.”

It goes without saying that “you had to be there.” Everyone was sure that if the event had somehow been amplified nationwide (a given in the YouTube age), it might have changed history, or at any rate, made Earth Opera famous. But by the time Electra recorded and released “The American Eagle Tragedy” only 80 percent of the original excitement, if that, survived. Worse yet, instead of ending the album, this cry from the heart was followed by the weakest, silliest track, “Roast Beef Love,” a song not even written by Rowan, whose other compositions on the LP, especially “Home to You” and “All Winter Long,” are lasting testaments to the very special music created by this short-lived band.

Way Beyond the Shore

“Discontent” — the word jumped out at me again from the pages of Monday’s New York Times in more than one reference to the state of the nation and the presidency. Now, back in the fantasy, let’s imagine that after absorbing the power and glory of Louis Armstrong’s “West End Blues,” President Obama could hear “The American Eagle Tragedy” as we heard it in the summer of 1968. Those lines about armies extended “way beyond the shore” still sting in the summer of 2010.