|

|

Vol. LXIII, No. 49

|

|

Wednesday, December 9, 2009

|

|

“In the morning [he] could direct the action of two thousand extras, and in the afternoon decide on the colors of Clark Gable’s coat and the shadows on Vivien Leigh’s neck.”F. Scott Fitzgerald on Victor Fleming

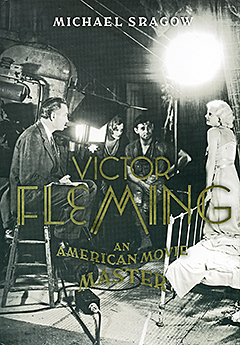

The quote comes by way of Sheilah Graham in Michael Sragow’s lively and illuminating biography Victor Fleming: An American Movie Master (Pantheon $40), which has overturned some long-held misconceptions of mine about this underrated and misunderstood filmmaker, who died suddenly in 1949. Born in 1889, he made his first picture in 1919, his first talkie in 1929, and in 1939 he spearheaded the filming of two movie legends, The Wizard of Oz and Gone With the Wind.

Asked about Fleming’s reputation as a “tough, sadistic” director, Gone With the Wind’s famously hands-on producer David O. Selznick said, “I don’t think he was sadistic. He was another of that extremely masculine breed. The most attractive man, in my opinion, who ever came to Hollywood …. Women were crazy about him and understandably so.”

Women and children both, in fact. After being slapped by Fleming to shock her out of a “fit of giggles” during the making of The Wizard of Oz, 16-year-old Judy Garland overheard him asking someone to “bop him on the nose” because of what he’d done to her. “I won’t do that,” she told him, “but I’ll kiss your nose.”

Ingrid Bergman, who plays the ill-fated barmaid Ivy in Fleming’s version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1941), also encountered some serious physical “direction” when she couldn’t make herself cry in the scenes where Spencer Tracy’s Mr. Hyde is tormenting her. “I just couldn’t do it,” she recalls in her autobiography, My Story. “So eventually he just took me by the shoulder with one hand, spun me around and struck me backwards and forwards across the face — hard — it hurt …. I was shattered by his action. I stood there weeping.”

Tears or no tears, Bergman’s Ivy is a wonder, and she knew it. “I’ve never been happier,” she wrote in her diary. “For the first time I have broken out from the cage which encloses me, and opened a shutter to the outside world. I have touched things which I hoped were there but I have never dared to show …. It is as if I were flying. I feel no chains. I can fly higher and higher because the bars of my cage are broken.”

Obviously it took a power more complex than that slapping around to set her free. (She praises Fleming, Tracy, and cameraman Joseph Ruttenberg in the same entry.) It’s no surprise to learn that Fleming and Bergman became lovers, an affair that lasted right up to his death, which occurred shortly after he directed Bergman in Joan of Arc.

Less Celebrated

With all its splendors, Gone With the Wind doesn’t interest me as much as the two less celebrated films Fleming made during the same period. Until I read the back story in Sragow’s book, I’d dismissed Captains Courageous (1937) as another glossy M-G-M box office blockbuster. I had no desire to see Spencer Tracy and 12-yearold Freddie Bartholomew chew up the emotional scenery. As for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, the notion of Tracy in the title role seemed unpromising at best. It didn’t help that the only glimpses I’d had of either film had been on below average prints cut to pieces by television commercials.

Extraordinary Moments

Amazing what a difference an immaculately remastered DVD makes. There are shots of Ingrid Bergman in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde so luminous you can’t believe your eyes. As Sragow says, “Everything about her is erotic and touching, from her voluptuous form to her Scandinavian-cum-Cockney vocalizing.” Odd as it sounds, the glow of her beauty is so outlandish it makes you feel like laughing out loud. Odder still, so does Spencer Tracy’s borderline campy intensity as Hyde in two extraordinary scenes with Bergman, even as he’s viciously toying with her, stabbing her with one deeply sarcastic, smoothly sneering remark after another. Tracy may seem miscast as the good doctor; he looks a bit silly in the mad-scientist lab (who wouldn’t?). But as Hyde he surpasses himself, like Bergman, touching things he “hoped were there but … never dared to show.”

While Fleming deserves credit for inspiring Bergman and Tracy to reach such heights, Tracy is in a very real sense his own director here. He’d wanted to play Jekyll and Hyde for years, his goal to create a divided personality without resorting to the crude, all too obvious over-the-top horror-movie makeup job that makes Fredric March’s ape-man Hyde an almost laughable, quasi racist caricature of evil (imagine Jerry Lewis combined with a psychotic minstrel man) in the earlier version directed by Rouben Mammoulian. Tracy wanted “to steer Hyde away from out-and-out monstrosity,” according to Sragow, who describes “the relatively spare makeup adjustments,” which were to “flare Tracy’s nostrils and sharpen his nose, give him devilish laugh-lines around unblinking eyes, and make his mouth more simian and his mane and eyebrows more ominously hirsute.” What’s so chilling about the scenes where Hyde is taunting and torturing the poor girl is the semblance of the kind, genial, courtly Dr. Jekyll still hauntingly visible in a countenance possessed by manic ferocity, so that at the last fateful moment when he insinuates that her “angel” and this devil are one and the same, she’s face to face with the truth, a recognition so monstrous as to be fatal in itself.

These harrowing scenes almost make you forget that you’re watching a movie seemingly sanctioned by the likes of Louis B. Mayer. For Tracy, it’s a moment of truth where the actor breaks loose and soars in a rapture of delight in sheer evil, like a satanic poet crooning over his victim, wounding her with every word, his tone all the more hideous because it sounds soothing: he’s making a travesty of the compassion shown her by his other half, and the terms of his inventive, eloquent abuse illuminate Stevenson’s conception. The rich doctor with his upper class friends (who disapprove of the godless implications of his research) and his proper, lovely fiancée (Lana Turner, who is excellent in the role) would despise himself — if he ever admitted it — for his attraction to the lowly barmaid (even if she is Ingrid Bergman). So it makes class-bound sense that he mocks Ivy, who wants to go out to a music hall, by suggesting they might attend a symphony at the Albert Hall, whereupon he sits down at the piano, spits out a grape seed, and plays something classical and elaborate while speculating on what they could do if they don’t go out. “We could play cards …. Or you could read to me, yes. Milton’s Paradise Lost would be nice.” Crooning: “But we haven’t the book, have we? And —” with exquisitely muted sarcasm, “I don’t suppose you know it from memory.”

All this cunning torture is building toward the moment when he forces her to sing the happy, jaunty tune she sang when she was a barmaid. In the 1932 version, when March’s Hyde makes his Ivy sing, it becomes a horror movie caricature in which Miriam Hopkins’s Ivy is little more than “a saucy wench.” Because Bergman’s Ivy is so much more human and vulnerable in her trembling beauty, and because Hyde’s brutality is far more subtle and devious, the dimensions of the evil are tremendous. It’s like watching “a thing of beauty” defiled, abused, and finally destroyed.

Extraordinary Freddie

In spite of truly gifted child actors like Shirley Temple, Mickey Rooney, Judy Garland, and Margaret O’Brien, one of Hollywood’s perennial sins over the years has been the sentimental exploitation of children for insulting-to-the-emotional-intelligence effect. Which is one reason I steered clear of M-G-M’s version of Rudyard Kipling’s Captains Courageous and the rich, spoiled schoolboy played to sickening excess (I assumed) by Freddie Bartholomew. According to Sragow, by the way, Kipling disapproved of MGM’s original treatment of the book, particularly the attempt “to inject the story with sex.” In fact, there are for all purposes no women in the film. None.

L. B. Mayer decreed that young Jackie Cooper had to blubber and sob when he said goodbye to his pirate pal, Wallace Beery at the end of Treasure Island (1934), which was also directed, though much less effectively, by Victor Fleming. Any tears shed by Freddie Bartholomew’s Harvey for Spencer Tracy’s great-hearted Portugese fisherman Manuel are earned. The pre-teen actor is brilliantly believable from the moment he opens his mouth. There are no false moves, not one. You never doubt Bartholomew’s transformation from a spoiled little Machiavelli, suspended for a semester from a boys’ school in Connecticut, to a member of the crew of a fishing boat called We’re Here, and you never doubt the love that develops between young Harvey and the life-force called Manuel. It’s true that Tracy’s accent verges on Chico Marx at times, but who cares — it’s a magnificent performance, worthy of the Oscar he got for it, one he should have shared with his co-star.

Victor Fleming deserved an Oscar himself if only for the way he handled his Gloucester fishing crew and the action scenes, the race with another boat, the life on board the ship, every detail vivid and true, including the banter among the crew, and even the posturing by the inimitable Lionel Barrymore. As Otis Ferguson wrote at the time of the picture’s release, the cameras “perform a constant miracle of walking on the waters,” as well as showing “an uncanny genius for the shipshape”: “Indeed the whole MGM staff has treated this film with so much respect and shrewd artistry that the treatment seems almost unsatisfied, as if it were mutely in search of some bigger theme.”

Kipling, Stevenson, Margaret Mitchell, and Frank L. Baum provided the bigger theme that Victor Fleming helped articulate, whether directing two thousand extras or seeing to the shadows on Vivien Leigh’s neck.

DVDs of all the films mentioned here are available at the Princeton Public Library. The image on the cover of Michael Sragow’s biography shows Victor Fleming on the set of Red Dust (1932) with (from left) Mary Astor, Clark Gable, and Jean Harlow, who, like Ingrid Bergman and Spencer Tracy, flew “higher and higher” when Fleming helped break the bars of her cage.