|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 50

|

|

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

|

|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 50

|

|

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

|

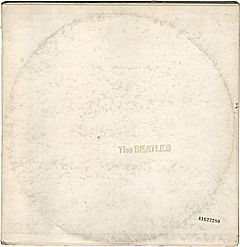

ONE IN FIVE MILLION, give or take 4,627,280, this being the cover of the reviewer’s copy of The White Album, complete with smudges, 40 years of ringwear, and the cosmetic embellishment to bring out the lettering of the title. According to various sources, it was Paul McCartney’s idea to stamp each copy of the first issue with an individual number, as if “The Beatles” were a limited edition of five million. Number 0000005 just sold on eBay for £19,201.

|

Forty years after John Lennon sang “Mother Superior jump the gun” in a song dripping with drugs and sex and rock ‘n’ roll cynicism, the Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano and Vatican Radio have not only announced a rationale for his widely misinterpreted 1966 statement that the Beatles were “more popular than Jesus” (“a boast by a young man grappling with sudden fame”), they have officially acknowledged the 40th anniversary of the the White Album, praising its music for being more “creative” than the “standardized, stereotypical” songs being produced today. With Rome weighing in — a proclamation from on high — how can I not celebrate that record?

Loud and Clear

When the White Album, formally titled The Beatles, was released in the U.S. on Monday, November 25, 1968, Barack Obama was seven years old and living in Indonesia, and Richard Nixon had been elected president, thanks in great part to Vietnam, the youthquake the Beatles were the epicenter of, and the assassination of Robert Kennedy.

The New York stations were already playing the album when we turned on the bedside radio that Monday morning. Imagine hearing “Back in the U.S.S.R.” loud and clear for the first time. What a lift, the sound of that jet scream of pure energy shaking the wooden frame of our little Sony clock radio at so dispiriting and traumatic a time, with the country torn apart and about to be further polarized by Nixon, Agnew, and company. The play on U.S./U.S.S.R. gave the number topical clout, but it needed no message (decades later we’d learn how deeply “Back in the U.S.S.R.” affected Soviet youth, some of whom are running the country today). Better still, the song that followed Paul McCartney’s message of headlong rock and roll jubilation was John Lennon’s “Dear Prudence,” a passionately sung and played anthem to life and light that made a fitting sequel to “Hey Jude,” the saviour of the summer of ’68 whose endless ecstasy of an ending has been called “the Sistine Chapel of rock ‘n roll” (speaking of the Vatican), especially if you listen with headphones.

Within days I found myself writing a letter to the New York Times scolding them for polluting their pages with a sloppy, clueless put-down of the album by one Mike Jahn, whose name shall forever live in infamy. A few days later, after what must have been a torrent of letters like mine, the Times ran a worthy appreciation by Richard Goldstein.

The Negatives

Okay, let’s consider the downside of this four-sided monster. It’s true that the recording sessions were fraught with conflict, angst, and resentment, that the group was coming apart, and that the album might have been even better had the best of it been packed onto one disc instead of two. The only other negative I can think of at the moment is the Manson connection, which grew out of the mind-set perpetuating the rumor that Paul McCartney had been killed in an auto accident in 1966. The rumor came to achieve a mystique of its own, with people close-reading lyrics and suspicious noises at the ends of certain tracks, looking for clues and codes (like “I buried Paul” at the end of “Strawberry Fields Forever”). Since so many incitable and excitable members of the vast audience were inclined to imagine that the Beatles were seers, what with their almost unimaginable influence worldwide, it’s no wonder that a two-bit Svengali like Charles Manson would find hints of apocalypse in a beautiful song like “Blackbird,” cues for murder and mayhem in “Piggies” and “Helter Skelter,” and evil innuendoes in “Revolution 9.” Though the Paul-is-dead hysteria had died down a bit by the time The Beatles came out, the group was still teasing the purveyors of that exercise in inventive mass paranoia with songs like John Lennon’s “Glass Onion” (“Well here’s another clue for you all/The walrus was Paul”) and in the big, fold-out lyric insert, on the other side of which was a pastiche of photos headed by one of Paul looking dead, face up in a pool of soapy water.

The dynamic driving the album’s first two numbers sounds no less potent now than it did 40 years ago, even with the bonfire of surface noise created by four decades of heavy playing. Other sequences that encapsulate the magic are the Side Two grouping of McCartney’s brisk and buoyant “Martha, My Dear” with Lennon’s drugged out “I’m So Tired” moving into the sublime with McCartney’s “Blackbird.” Or the threesome at the end of the same side where McCartney’s wild, instant rock classic, “Why Don’t We Do It in the Road?” segues into his almost too-too lovely love song, “I Will,” which is matched by Lennon’s hymn to his dead mother, “Julia.” All three songs are essentially solo numbers, typical of the every-man-for-himself recording environment. But like everything else in the album, the playing is strong and the music coheres, the raw meshing with the tender, lust with sorrow.

The Absolutes

Given the fact that almost everyone who loves the album can cite songs they could live without, and that both George Harrison and producer George Martin thought that a single fantastic album could have been sculpted from the double set, it might be helpful to see if it’s possible to separate the can’ts from the cans. For me, the absolutes are (again) “Back in the U.S.S.R.” and “Dear Prudence,” along with “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” (with Eric Clapton doing an uncredited turn, Harrison-style, in Harrison’s epic lament); “Happiness is a Warm Gun” (wherein Lucy in the Sky comes down to earth and jumps the gun); “Martha My Dear” (Mozart would approve); “I’m So Tired” (Lennon’s gritty sequel to Revolver’s “I’m Only Sleeping”); “Blackbird” (Keats and Mozart would approve); “Why Don’t We Do It in the Road” (Paul’s rock DNA in eight words); “Julia” (said to be about Yoko as well as John’s mum); “Mother Nature’s Son” (Schubert and Thoreau would approve); “Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except for Me and My Monkey” (a clanging five-alarm fire engine of a song); “Sexy Sadie” (with the glory of its stately, march-time middle eight supporting Lennon’s sweet send-up of the Maharishi); “Helter Skelter” (a great, mad, bludgeoning rollercoaster thundering off the rails when heavy metal was only a gleam in the devil’s eye); “Cry Baby Cry” (the most haunting song on the album: “with voices out of nowhere/Put on specially by the children for a lark”); and “Good Night” (if only because Ringo’s doing the singing and it’s the perfect lights-out, we’re-all-together-now closer).

The Others

After putting together a magnificent LP with that bunch, you’d still have enough left over for an album most mortal groups would be happy to give their name to. But consider what would be lost. The indispensably enigmatic, adventurous ambience of The Beatles would be violated if you took away “Revolution 9,” an extended and much-maligned soundscape that has no redeeming melodic or rock and roll value but that creates something moody and ominous harking back to “Tomorrow Never Knows” on Revolver and “A Day in the Life” on Sgt. Pepper while further complicating the mixed message of “Revolution 1” (“count me out/in”) and the hard-rocking mixed message of the original “Revolution” that preceded it as the B side of “Hey Jude.” And look what else you lose. Paul’s “I Will” is expendable only because it shows signs of trying for melodic perfection rather than simply being perfect and beautiful, like “Blackbird,” “Mother Nature’s Son,” and “Martha My Dear.” Maybe we could live without the terminally infectious “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” but why do we have to? Paul’s “Rocky Raccoon” and John’s “Bungalow Bill” may be throwaways compared to the gems, but they make a nice pair of story songs. Anyway, when a whole industry has evolved from bootlegging and giving legitimate release to just about everything the Beatles ever did, why draw the line at two such characteristic John/Paul flights of fancy? The point of a big album, like a big novel, or any work of art on the grand scale, is to give the illusion of something as big and various as life.

I still haven’t mentioned the other losses, including three songs by George, whose compositions on Revolver were far superior to these three and who a few years later would produce an indisputably great double record set in All Things Must Pass. Between “Piggies,” which seems snide and small, and the chug-chugging saxes of “Savoy Truffle,” the song I’d miss most is “Long Long Long,” which closes Side 3 on a note of hushed serenity that echoes the yearning quality “Julia” brings to the end of Side 2.

So, what’s left? “Birthday” is a terrific rocker if not quite up to the standard of “Back in the U.S.S.R.,” while the straight version of “Honey Pie” on Side 4 sounds as if it’s been salvaged from the music hall hope chest that gave us Sgt. Pepper’s “When I’m 64.” But take it off and you lose one of those nifty album-to-album references that make the Beatles a world unto themselves. As far as that goes, “Glass Onion” would deserve a place even if John claims that it was “tossed off” as bait for Beatles scholars and portent mongers. It also helps that it’s performed with his inimitable force and feeling. And with a singer as great as Lennon, there’s no such thing as “tossed off.” Having said that, the one cut I’ll admit to skipping over now and again is “Yer Blues,” a screamer that can’t compare with Lennon’s singing on other songs, especially “Happiness is a Warm Gun,” his inspired blending of EuroPop, roadhouse blues, doo-wop, and The Naked Lunch. Which brings us finally to Ringo’s “Don’t Pass Me By,” which, like “Good Night,” could be justified if only because Ringo’s lovably unaffected singing seems downright refreshing when it’s surrounded by so much virtuosity. Like every one of his few recorded songs, it has the special goofy charisma he brought to the Beatles dynamic (remember the funny guy who stole A Hard Day’s Night and was the true protagonist of Help), in addition to being an amazingly adept and tasteful drummer.

The entry for The White Album on Wikipedia is worth checking out. I didn’t know that the title was at one time going to be A Doll’s House, nor that it has outsold all the other Beatles albums. It’s safe to say that it may also prove to be the only rock album ever recommended by the Vatican, whose “review” proclaims it “a magical musical anthology: 30 songs you can go through and listen to at will, certain of finding some pearls that even today remain unparalleled …. A listening experience like that offered by the Beatles is truly rare.” “Magical! Unparalled! Truly Rare!” A-men.