|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 50

|

Happy Holidays!

|

Wednesday, December 15, 2010

|

The world is changing Your heart is growingfrom ”Cartwheels”

Listen to songs like “Mother Rose,” “Cartwheels,” “Peaceable Kingdom,” and the title track from Patti Smith’s 2004 album, Trampin’, and you begin to understand what helped the so-called “punk icon” or “godmother of punk” find her way to the heart of her National Book award-winning memoir, Just Kids (Ecco paper $16). These are the songs of a loving, knowing, abiding mother, daughter, lover, wife, and, above all, undaunted artist/poet/storyteller devoted to keeping the promise she made to Robert Mapple-thorpe. Remembering their last conversation in a note to the reader included along with 15 additional pages in the handsome, recently released paperback edition, she quotes Mapplethorpe as if she and he were one voice in her consciousness: “I told him I would continue our work, our collaboration, for as long as I lived. Will you write our story? Do you want me to? You have to he said no one but you can write it. I will do it, I promised, though I knew it would be a vow difficult to keep.”

In Just Kids, she keeps her vow. Beyond that, her commitment to expressing what they shared frees her to tell a still larger story in which her devotion extends to everything from New York City in the last years of the sixties to the gods of rock and roll to “Vissi d’arte,” the aria from Tosca (“I have lived for love, I have lived for Art”) that she’s listening to on March 9, 1989, when she’s told of Mapplethorpe’s death. The emotional current running through the most deeply felt songs in Trampin’ is very much there in her memoir. It’s love at first sight when at age 16 she’s struck by her “archangel” Rimbaud’s “haughty gaze” on the cover of Illuminations in a Philadelphia bookstall. Another inspirational force guiding her through the book of her life is William Blake, who embodies the providential mixture of poetry, craftsmanship, art, and mysticism she reveres and believes has determined the course of her life from the moment a childhood visit to the Philadelphia Museum of Art revealed that “to be an artist was to see what others could not.” In “My Blakean Year,” another song from Trampin’, the refrain is “One road was paved in gold, one road was just a road.”

Patti and Keith

Just as reviewers writing about Keith Richards’s Life admitted being surprised that a book of such merit could come from a man who had supposedly blitzed his brain with drugs, more than one writer applauding Just Kids has confessed to having a preconceived notion about what sort of a book Patti Smith would produce. Janet Maslin says as much in a New York Times review that praises Smith for casting off “all verbal affectation” and writing “in a strong true voice unencumbered by the posturing mannerisms of her poetry.” It’s also a voice that can be playful, as when she recounts how Keith helped her change her image early on. After gathering up all her rock magazines, she cuts out and studies every picture of Richards she can find and then takes a pair of scissors to her long straight hair, “machete-ing” her way “out of the folk era.” Not only was it a “liberating experience,” it “elevated” her “social status” (“My Keith Richards haircut was a real discourse-magnet”).

Saving Grace

Love ties everything together in Just Kids. Even the darkly Faustian turn Mapplethorpe’s life and work take is encompassed by the author’s love and faith. After describing how he begins creating “visual spells” that “might serve to call up Satan, like one would a genie,” she writes of visiting St. Patricks Cathedral on break from her job at Scribners Bookstore “to pray for the dead, whom I seemed to love as much as the living: Rimbaud, Seurat, Camille Claudel, and the mistress of Jules Laforgue.” She also prayed for Mapplethorpe, whose own “prayers were like wishes. He was ambitious for secret knowledge. We were both praying for Robert’s soul, he to sell it and I to save it.”

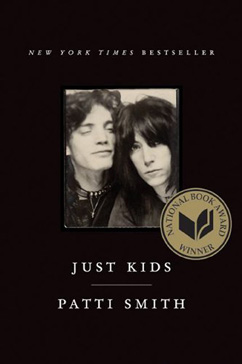

Smith’s nuanced phrasing indicates the feel for language that puts her book a literary step or two above other memoirs. Among the features setting Just Kids apart is her fervent belief that it represents in its essence a prayer for Robert Mapplethorpe’s soul. At the same time, she’s using him in the making of her art the way a novelist employs a fascinating character. In the striking, somewhat eerie cover photo of the two of them, his eyes are closed while hers are open and alert, allowing you to imagine that he’s either dreaming or already dead. It’s interesting that the relationship begins when in order to escape the unwelcome advances of another man, she casts Mapplethorpe as her boyfriend, setting up a scene played out in numerous old Hollywood movies. She thanks him (“You saved my life”), he takes her hand and they wander through the East Village; he buys her an egg cream at Gem Spa, she tells him the story of her life, he smiles and listens, and later tells her that he’d been tripping on acid the whole time.

Beloved Camden

Smith’s account of the moment she sets out to seek her fortune is almost too good to summarize. After bringing a baby into the world at 20 and placing it in the care of “a loving and educated family,” she’s been dismissed from Glassboro State Teachers’ College, laid off from her minimum wage job at a textbook factory, is on the waiting list for a job at the Campbell Soup Company in Camden, and has just enough money to pay for a one-way bus ticket to New York. Her waitress mother has given her a uniform and a pair of white wedgies to pack while telling her “You’ll never make it as a waitress … but I’ll stake you anyway.” The inspiration for the adventure being her archangel Rimbaud, she tosses her copy of Illuminations into a plaid suitcase (“We would escape together”) and catches the Broadway bus to Philadelphia, “passing through my beloved Camden and nodding respectfully to the sad exterior of the once-prosperous Walt Whitman Hotel. I felt a pang abandoning this struggling city, but there was no work for me there. They were closing the great shipyard and soon everyone would be looking for jobs.” It was July 3, 1967, in what was known, at least on the other coast, as “the summer of love.”

That’s only one instance of the way Smith highlights the most telling details of her story, whether she’s going into a Philadelphia phone booth on that first day of freedom (“It was a real Clark Kent moment”) or referring to her “East of Eden dress” or picturing the Chelsea Hotel as “a doll’s house in the Twilight Zone.” She’s wearing her “gray trench coat and Mayakovsky cap” at the Automat when she encounters Allen Ginsberg, who loans her a dime and tries to pick her up — until he finds out she’s not the “very pretty boy” he thought she was. Again and again, she shines her allusive intelligence on occasions such as the night when she and Robert rescue a friend who is perched high on a crane in the dead of winter and refuses to come down. Grabbing the black lamb toy Robert had given her (“his black sheep boy to black sheep girl present”), she climbs the crane and gives her friend the lamb: “We were the rebels without a cause and he was our sad Sal Mineo. Griffith Park in Brooklyn.”

Smith doesn’t have to mention James Dean by name to nail the cinematic association in that scene, no more than she does every time she refers to that “East of Eden” dress (she also has a “Song of the South” outfit). It’s the poetry of the culture that she and many of her readers grew up with and that can also be found in Bob Dylan’s Chronicles, which evokes New York in the early sixties much as Just Kids does in the latter part of the decade. The difference is that Dylan stands to one side, half-facing his audience, in effect, while Patti Smith gazes right in your eyes and calls you closer, singing as she does in “Mother Rose,” “Come to me Take my hand/Look into your heart There I’ll be.”

The last stop on Patti Smith’s book tour, which touched down in Princeton last week, will be at the 92nd Street Y in New York, January 6, 2011, at 8 p.m. Trampin’ is available at the Princeton Public Library and can also be heard and sometimes seen on YouTube.