|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 52

|

|

Wednesday, December 26, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 52

|

|

Wednesday, December 26, 2007

|

|

There are lots of nice moments this time of year, but maybe the nicest is when the cats first notice the tree in the living room. This is their fifth tree, so they seem perhaps a little less bowled over than in previous years, but no less appreciative. Brother and sister tuxedo look at the Fraser fir with big googly Felix the Cat eyes and then they cock their heads toward their benefactors as if to say “All for us?” This is above and beyond the call of duty. Water in the stand, just for them. Nice packages to lie on, just for them. And how thoughtful, to hang all those glittery things on the branches, even though they know by now they aren’t supposed to use them for punching bags — except for the sister, who always has to knock off an ornament or two, in case her human slaves think she’s getting less crazed in her middle age.

The cats always keep their distance until we’ve finished fixing up the tree and lighting it for them, probably because music is playing, and since it’s usually music by Hector Berlioz, they lay low, still not quite over the shock of hearing the manifold trumpets of the “Day of Judgment” the night when the full, top-volume force of the “Dies Irae” and “Tuba Mirum” of the Requiem seemed to lift the living room ceiling and blow it to the moon. But they should know by now that the music of choice for the benign ritual of the tree is the “Shepherds’ Farewell” from L’Enfance du Christ, which is about as far from the apocalypse as you can get. Of course that’s the yin and yang of Berlioz, whose birthday coincides with tree-trimming week; his 204th was on December 11. Who else can compose music at once so tender and so tremendous? It should be noted that our choice of ceremonial accompaniment transcends all religious considerations. This is beauty for beauty’s sake, beauty that could or should touch the heart of anyone with or without a faith. It doesn’t matter whether these shepherds are on their way to or from Bethelem or Mecca or Brisbane or Brooklyn. What matters is the hushed, simple, swelling beauty of the singing and the gentle grace it lends to the ritual of the tree. It’s like the cats seeing the tree; it’s simply what it is: a thing of wonder.

Thanks to some people who felt like sharing it with the world last week, several performances of this haunting music have surfaced online on YouTube. Since the Brisbane Concert Choir’s version seems to have been swallowed up in cyberspace, you may have to make do with the one from the Stetson University Orchestra and Chorale Union, which is actually even better because the sound is fuller and richer, and the scene is shot from the rear of the church so that you can see several workaday women with coats and bags straggling into the realm of glorious music. Somehow it’s almost as good watching the cats discover the tree.

Berlioz Face to Face

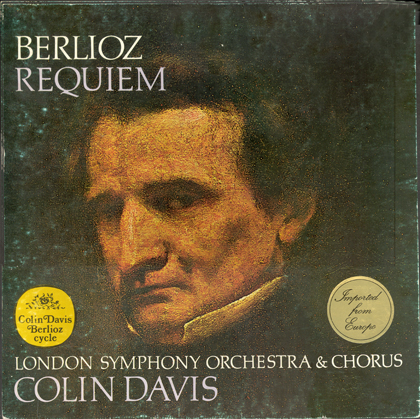

The image of the composer accompanying this article, from the cover of the Colin Davis/London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus recording of the Requiem, reminds me of one Christmas Eve when the face on the album seemed to be illumined by candlelight as it stared out of the shadows. The composer was over there by the stereo, like a more companionable version of Marley’s face appearing on Scrooge’s door-knocker. This pleasant visitation was no doubt due to the fact that I’d been listening almost exclusively to Berlioz that winter, The Damnation of Faust, Romeo and Juliet, and the Requiem in particular, the “Shepherd’s Farewell” not then being as synonymous with the season as it is now. On the Christmas Eve in question, my ears were still ringing from the Requiem. If you ever want to experience levitation, just listen to the “Day of Judgment” with headphones. It’s as close as music comes to being an act of nature — a tempest created by the man Heinrich Heine called a “gigantic nightingale, a lark the size of an eagle.”

I came to Berlioz through his Memoirs, after a nudge from the composer’s friend Balzac. Only the author of the Human Comedy could have created so fantastic and compelling a character. Like other Balzacian artist heroes, Berlioz is a warrior genius in the battle of life. During the first public performance of the Requiem, when the conductor laid down the baton to take a pinch of snuff on the very verge of the “Day of Judgment,” Berlioz pushed him aside, stretched out his arm, and “marked out the four great beats of the new tempo.” Describing another early performance of the same work, which he conducted himself, he speaks of “my forces,” using terms more suited to a military engagement than a religious ceremony: “Everyone alert and with me to a man, orchestras and chorus [not a single orchestra but orchestras, including four brass bands], each one at his post, nothing wanting, we began the “Dies Irae”…. The chorus received the orchestral onslaught without flinching; the fourfold fanfare pealed forth from the four corners of the stage, the air shook with the roll of ten pairs of drumsticks and the tremolo of fifty bows unleashed, and in the midst of the tumult of baleful harmonies, the blast from beyond the grave, a hundred and twenty voices proclaimed their tremendous prophecy.” And what was happening to the composer while the storm he’d created was raging? His heart was “going like a bell,” his knees were shaking, his brain “spinning like a mill-wheel.” He almost passed out, in fact.

Father Shakespeare

One of the many wonders we have to thank Shakespeare for is the music his work drew from Berlioz, who was galvanized by performances of Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet, among the plays presented by John Kemble’s English company in Paris in 1827. It’s true that he was also possessed by Virgil’s Aeneid (thus Hector’s opera, Les Troyens), but that grew out of a boyhood passion. His devotion to Shakespeare was deeper. It helped, of course, that he fell in love with and eventually married Harriet Smithson, the Irish actress who played Juliet and Ophelia in those performances; it was in coming to terms with her untimely death that he was moved to a statement of faith in one of the most memorable passages of the Memoirs. After describing “the horror” and “pity” of her “long vista of death and oblivion,” he prayed:

“Shakespeare! Shakespeare! I feel as if he alone of all men who ever lived can understand me, must have understood us both; he alone could have pitied us, poor unhappy artists, loving yet wounding each other. Shakespeare! You are a man. You, if you still exist, must be a refuge for the wretched. It is you that are our father, our father in heaven, if there is a heaven…. Thou alone for the souls of artists art the living and loving God. Receive us, father, into thy bosom, guard us, save us!”

Barzun and Davis

As Arthur Krystal points out in his October 22 New Yorker piece on Jacques Barzun (“Age of Reason,”), Barzun and Colin Davis are the two living men who had the most to do with the gigantic nightingale’s finally attaining his rightful place in the pantheon (both men also recently celebrated landmark birthdays, Barzun turning 100 on November 30, and Davis 80 on September 25). Only half a century ago Berlioz had been consigned to the sidelines as a freakish purveyor of the Romantic style, all “disorder and bombast.” Since Barzun’s book, Berlioz and the Romantic Century, was, according to Davis, “part of my education,” the author can rightfully claim some of the credit for the masterful Colin Davis/London Symphony Orchestra recordings of all Berlioz’s major works. In case you doubt Barzun’s devotion, when he was provost at Columbia he replaced the music played at graduation with the march from Les Troyens.

What the Cats Know

I hope Alicia Ostriker won’t mind my amending a passage from her book, For the Love of God, which I reviewed recently: “A purely coherent and consistent Christmas would never have been able to command the millennia of loyalty the season has commanded. It would lack mystery. It would be reduced to the flattest sort of theology. We need the layering, the tension, even the absurdity of Christmas.” With “Christmas” in place of “Bible” and “scripture,” you have a fair statement of how it seems at this time of year, when there’s always somehow room in the absurd, tense, frantic holiday element for a little poetry or music and a craving for something beautiful and unspoiled, whether it’s faith, devotion, love, mystery, or even the absurdity of hauling a tree into the house and decking it out with ornaments and lights while music composed more than 150 years ago is playing. It would be nice to think that by engaging in this simple, harmless ritual people are somehow contributing to the most positive essence of the season, regardless of their religion or politics or taste in music, and that on some level they’re as innocently in touch with the special holiday feeling as our cats are. Cats don’t know about the birth of Christ and they don’t care that certain grinches on Fox News are trying to politicize Christmas and further polarize an already deeply polarized country by claiming there’s a liberal conspiracy to destroy a Christian holiday. The cats don’t know about Scrooge and Marley or Bush and Cheney. All they know is that once a year we bring a tree in from the outdoors and hang lots of pretty toys on it, just for them.