|

|

Vol. LXV, No. 5

|

Wednesday, February 2, 2011

|

If more politicians knew poetry and more poets knew politics, I am convinced the world would be a little better place in which to live.Senator John F. Kennedy, at Harvard’s 1956 commencement

According to a CNN poll conducted to mark the 50th anniversary of the inauguration of John F. Kennedy on January 20, 1961, 85 percent of “all Americans” approve of the way he “handled his job as president,” ranking him first among the chief executives of the last half-century. Stories based on the poll were headlined “Kennedy Most Popular President.” The phrase “handled his job as president” assumes some knowledge of what Kennedy accomplished in office. In fact, he would almost certainly be the “most popular” chief executive regardless of what his administration did or didn’t accomplish. On top of that, the majority of the respondents ranking Kennedy, meaning those in the age group from, say, 18 to 60, were either not around when he was president or not old enough to understand what was going on.

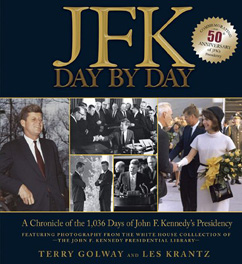

JFK Day By Day: A Chronicle of the 1,036 Days of John F. Kennedy’s Presidency (Running Press $27.50), edited by Terry Golway and Les Krantz, may be the simplest, handiest way to find out what Kennedy did or tried to do in the oval office. Although there’s no Night by Night accounting, this handsome volume featuring photography from the Kennedy Library does at least recognize the existence of the president’s infidelities. There’s a reference to his “almost madcap” sex life and to the time the First Lady was giving a tour of the White House to a French journalist and pointed out a “young female secretary,” informing the visitor, in French, that the president “was supposedly sleeping with her.” How classy is that? Jackie lets it drop in passing, oh by the way, and in French. As if anyone ever doubted it, a fair amount of Kennedy’s enduring popularity can be attributed to the First Lady.

One way of appreciating the quality in John Kennedy that people still respond to is to picture Richard Nixon standing at the podium on January 20, 1961, or being sworn in while Pat Nixon holds the Bible. It’s not just that Kennedy was smarter, younger, better looking, and a stronger speaker. JFK had a touch of the poet about him. For a start, can you imagine Robert Frost or anyone else reading poetry at a Nixon inaugural? Until Kennedy invited Frost, no poet had ever read at the inauguration of an American president.

Emerson’s Poet

Was Kennedy a poet? Not in the conventional sense, but in the unconventional, Emersonian sense, his appearance on the national scene and the posthumous appeal that makes him our “most popular” president accords with the ideal Emerson describes in “The Poet,” who “in looks and behaviour, has yielded us a new thought,” and “unlocks our chains, and admits us to a new scene.” As president, in Kennedy’s case, the poet “stands among partial men for the complete man, and apprises us not of his wealth, but of the commonwealth.” He “sees and handles that which others dream of, traverses the whole scale of experience, and is representative of man, in virtue of being the largest power to receive and to impart.” Poetry may have little to do with the fundamental details of the “job” Kennedy was handling, but there’s no doubt that it figures significantly among the intangible qualities that put him at the top of the CNN poll.

JFK’s admiration for Robert Frost grew out of something more than a ceremonial opportunity. Explaining why he’d invited the 86-year-old poet to read at the inauguration, Kennedy said, “I felt he had something important to say to those of us who are occupied with the business of government; that he would remind us that we are dealing with life, the hopes, and fears of millions of people.”

An unlikely fringe benefit of the sunny, subfreezing weather on Inauguration Day was that due to the glare and the cold, Frost was unable to read the lengthy poem he’d written for the occasion. Kennedy’s speech is 1300 words long. Frost’s poem runs to 560, and while his recitation of so loose and rambling a work (“There is a call to life a little sterner,/And braver for the earner, learner, yearner”) probably would not have seriously marred Kennedy’s inspired presentation, it might have challenged the patience of the audience. If, however, the poem had been telescoped to give prominence to the last couplet — “A golden age of poetry and power/Of which this noonday’s the beginning hour” — so quotable a line would have been picked up by the media, and repeated until it became a Camelot cliché.

Viewed on YouTube 50 years later, Kennedy’s inaugural address imparts abundant “poetry and power.” From the moment he calls out, in that raw, searing, just-shortof-strident voice, “Let the word go forth,” the speech is a series of ascending rhetorical fanfares that, if anything, seems more impressive now than it did at the time, perhaps because on first hearing, some of its more elaborate rhetorical flourishes seemed distractingly showy.

The Pardon

Watching Kennedy’s speech from a federal prison facility where he was serving a ten-year sentence for possession of drugs (extended because he refused to inform on others), the great jazz pianist Hampton Hawes saw “something about the look of him, the voice and eyes, way he stood bright and coatless and proud in that cold air.” Writing in his autobiography, Raise Up Off Me, Hawes recalls thinking “That’s the right cat; looks like he got some soul and might listen.” But when he suggests to one of the medical officers that he might apply for a presidential pardon, he’s told, “That’s the root of your trouble, Hampton. You refuse to be realistic.”

The same might be said for the future behavior of the generation that saw what Hawes saw in Kennedy that day. In Hawes’s case, he continued refusing to be realistic in spite of the obstacles that officials put in his path; it took him a year to find the name of a pardon attorney, and when he finally received an Application for Executive Clemency, he had to figure out an approach and round up letters of recommendation before sending the package to the White House. Four months later, on August 16, 1963, “the President of the United States came through.” The same officials who had scoffed at Hampton passed the document around in disbelief; no one had ever seen such a thing. What Hawes saw was “a blur of Gothic letters on parchment paper, about twenty ‘whereases,’ signed with the Man’s name.” Three months later “the Man” was assassinated.

Less than a month before November 22, Kennedy was speaking at Amherst at the groundbreaking ceremonies for the library named for Robert Frost, who had died the previous January. One of the peculiarities of the design of JFK Day by Day is that only certain days are highlighted with images and text while the actual inventory of daily events is in a column running along the righthand margin. Consequently, the reference to the October 26 Amherst speech appears on the same page with the events of November 23, headlined “America in Mourning,” and accompanied by pictures of the flag-draped coffin in the capitol rotunda and at a private mass. The juxtaposition hurts, particularly when you hear what Kennedy was saying at Amherst. In the voice that none of his impersonators has done justice to, he begins on the note that while “our national strength” matters, “the spirit which informs and controls our strength matters just as much.” He goes on to celebrate Frost’s coupling of “poetry and power” though without specifically referring to the unread Inaugural poem: “When power narrows the areas of man’s concern, poetry reminds him of the richness and diversity of his existence. When power corrupts, poetry cleanses.”

It’s the power of art and artists that Kennedy ultimately celebrates and he does so in terms relevant to the forces that will shape and define the decade and its most influential agents, not only writers, composers, and musicians, but the marchers and protesters living out their version of Kennedy’s suggestion that the artist “becomes the last champion of the individual mind and sensibility against an intrusive society and an officious state.”

With less than a month to live, Kennedy “looks forward to a great future for America, a future in which our country will match its military strength with our moral restraint, its wealth with our wisdom, its power with our purpose,” an America “which will not be afraid of grace and beauty, which will protect the beauty of our natural environment, which will preserve the great old American houses and squares and parks of our national past, and which will build handsome and balanced cities for our future.”

Salinger Wept

When in the Amherst speech Kennedy refers to the artist as a “solitary figure,” who has, quoting Frost, “a lover’s quarrel with the world,” and who, “in pursuing his perceptions of reality … must often sail against the currents of his time,” I thought of Hawes again, but, even more, the words conjured up the artist whose biography I wrote about last week. In November 1963 J.D. Salinger was just beginning the “lover’s quarrel with the world” that would lead to his long, silent, self-imposed exile. The spring before the assassination, he had been invited to the White House for a party to honor American writers and artists. According to his daughter Margaret’s memoir Dream Catcher, he “almost went, such were my father’s feelings for President Kennedy.” When Salinger hesitated, Jackie Kennedy called him up to ask him personally, but to no avail. He stayed home, and on November 24, 1963, like most of his fellow countrymen, he was in front of the television, described by his daughter “with tears rolling silently down his cheeks as he sat and stared. The only time I have ever seen my father cry in my whole life was the day he watched JFK’s funeral procession on television.”

If you want to hear or read the Amherst speech, it’s at http://arts.endow.gov/about/Kennedy.html. Two years later, President Johnson signed the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act, creating The National Endowment for the Arts.