|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 5

|

|

Wednesday, February 3, 2010

|

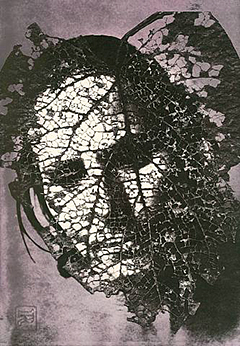

“EDITH IN PANAMA: LEAF MASK”: Among the most striking images in “Emmet Gowin: A Collective Portrait” is this gold-toned salt print from 2004. The exhibit, which features the work of the retiring Princeton professor and 20 of his former students, will be on view at the Princeton University Art Museum through February 21. |

Only chance can bring together new combinations in a way that is revolutionary. No one ever discovered anything really important intentionally.Emmet Gowin in a 1997 interview

Emmet Gowin’s comments about the element of chance in art reflect my own experience of his work. I had no intention of discovering him, but discover him I did. The first time was five years ago when I was covering an exhibition on another subject at the James A. Michener Art Museum (Town Topics 17 March 2004). It happened again at the Michener last fall (Town Topics 16 September 2009), and it happened yet again this past Saturday at the Princeton University Art Museum, even though my motive couldn’t have been more boringly intentional. I went there expressly to write about Emmet Gowin and I went prepared, having spent several hours exploring his photography online.

The subject of that 2004 exhibit at the Michener was engaging enough (“Rock On! The Art of the Music Poster from the 60s and 70s”) but it didn’t do much more than match my expectations. By the time I left I was suffering from museum fatigue and had an appointment to get to, so I seriously considered skipping the exhibit upstairs, Emmet Gowin’s “Changing the Earth.” Seen from the outer corridor, the arrangement wasn’t particularly compelling, being a fairly uniform alignment of framed black and white or sepia aerial views of bleak, wasted-looking landscapes. It took a firm push from Keats’s “magic hand of chance” to get me over the threshold into the gallery, which was empty. I was glad to have it to myself, to be able to absorb what I was seeing without listening to other people commenting or speculating about what this or that vision most resembled. Gowin’s imagery was eloquently to the point; it said, “Be quiet and look.” All that colorful psychedelia down in the relatively busy Wachovia Gallery was the work of talented mortals. Here were photographic acts of imagination, collaborations between the airborne camera and the designing forces of man, time, nature, and weather in drainage ditches, winter fields, golf courses, nuclear test sites resembling lunar landscapes, and housing projects and industrial parks everywhere from Kansas to the Czech Republic to the curious creations formed by the eruption of Mount Saint Helens. By the time I walked out the door into a lesser reality I was already violating the message of the imagery, my mind humming with the references to Cubism, Picasso, and Braque that eventually showed up in the review.

Nancy Happens

The next discovery, in September, was sparked by Gowin’s justly renowned Nancy: Danville, Virginia, which happened in 1969 when the photographer’s niece spontaneously assumed a fascinatingly unorthodox pose (arms entwined, each hand holding, presenting, displaying an egg). My use of the word “happened” reflects Gowin’s account of the dynamic of the moment, “the key” that “oddly enough” led him to understand that it was time to “take the whole world as a subject,” time to be more than “a family artist” (the essence of his work at that point having been images of his wife Edith and her family). As Gowin tells Sally Gall in a 1997 interview, “For 15 years I had been watching this family and I loved those pictures. If I thought anything was original in my work, it was accepting the here and now, and then letting it show me what was important. The little child crossing her arms and showing me those two eggs. She just came to me with two eggs and crossed her arms. And I thought, that is the wisdom of the body. To whatever extent that she knows it, it’s her body informing her. It’s the same kind of intuition that I wanted to work out of. If she could invent that much, the thing that I could do is be open to the invention. And that is, in essence, just how it happened.” In other words, let chance and invention — the wisdom beyond intention — inspire the discovery.

When the interviewer marveled at the gesture and the look on Nancy’s tensely impassive face (her eyes closed, head tilted back), Gowin said, “See, I never thought I did that. I always felt that life did that to both of us. It used her body to teach her, and it used her to teach me.”

When you come to the photograph of Nancy, which is not part of the Princeton show but easily viewable online, you more than see it, you feel it; it happens to you, and should you be on your way to another room as I was, it stops you as sure as a shout, turns you around, stirs your imagination and touches you at the same time. The effect can be likened to a chance meeting with someone else’s moment of truth, some 40 years after the fact.

A Fallen Seed

When I walked into the University Art Museum’s “Emmet Gowin: A Collective Portrait,” I wasn’t expecting to make any discoveries. Probably that’s the best way to approach anything, whether it’s an art exhibit or a walk across campus on a cold, windy day in January. The “Collective” refers to the inclusion of the work of Gowin’s former students as well as that of mentors and colleagues like Harry Callahan (1912-1999) and Frederick Sommer (1905-1999). The one piece not by Gowin that for me most powerfully embodies the chemistry of chance was done by the Class of 1980’s Laura McPhee. Her striking 76.5 x 95.6 cm chromogenic print of a banyan tree growing out of a 16th-century terra cotta temple in West Bengal is the image that introduces you to the show, the one that pulls you over, being posted at the entrance next to Gowin’s smaller, more delicately intimate, hauntingly subtle slice-of-life interior from 1967, Danville, Virginia, which, again, you don’t “see” so much as sense. It’s a brilliant pairing, like putting a haiku next to an epic. The idea that once upon a time a fallen seed lodged in a crevice in the roof of a temple with this magnificent result nicely accords with Gowin’s thoughts about chance creating extraordinary combinations.

A Brilliant Accident

Described as a “gold-toned salt print,” Edith in Panama: Leaf Mask (2004) at once affirms and counters the intention stated by the 25-year-old photographer in a hand-written letter from May 1967 displayed near the gallery entrance: “From the beginning, I wanted to make pictures so potent that I would not need to say anything about them.” In fact, this work, this third Gowin discovery, is so potent it would be unnatural not to at least try to describe what makes it so compelling. Like the picture of Nancy holding the eggs, it’s an image that calls you over. If you’ve been exposed to enough of Gowin’s work, you’ll have seen his wife in a wide array of poses and settings, erotic, homey, fanciful, funny, down to earth. To think “lovely” the instant you see a work like Edith and Moth Flight (an inkjet print from 2002) is a matter of pure instinct; it’s easily understood; a conscious combination of effects has produced an intriguing image. Not so easy is Edith in Panama. Its very suggestiveness demands something more of you. As far as I know, no other image of Edith takes you as close to her face as this one; this is a true, cinematic close-up. Or it could be a detail from an ancient mosaic; a piece of primitive exotica; the death mask of a poet, male or female, or a movie goddess, or a perhaps a glamour shot of a Pola Negri or a Garbo from the silent era, as if the gauzy “mask” were one of those embellishments favored by photographers creating the mystique of the stars in Hollywood’s Golden Age.

If you didn’t know the part chance played in the “Leaf Mask,” you’d assume that Gowin had done some embellishing himself, and so he did, as his note admits, in preparing the handmade paper, bleaching the silver out of an Agfa gelatin silver paper and “coating the surface with a light-sensitive solution.” But there was nothing aesthetically “intentional” about what Gowin did on his way back from a trip to Panama, which was to take a vine leaf from his sojurn there and press it between sheets of gray board, one of which happened to bear an image of Edith. When he got home and opened the press, there was the masked face, a “fortuitous composition” for him and for art.

“Emmet Gowin: A Collective Portrait” will be at the Princeton University Art Museum through February 21. The Museum is free and open to the public Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., Thursday, 10 a.m. to 10 p.m., and Sunday, 1 to 5 p.m.