|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 5

|

|

Wednesday, February 3, 2010

|

|

My father has, indeed, spent his life busy writing his heart out.Margaret Salinger in Dream Catcher

With the January 27 death of J.D. Salinger at 91, it’s not a question of “R.I.P.” or “The End” but “What now? What next?” In other words, hold on: you don’t wrap this writer’s life and work into a tidy obituary. Nor can you simply dismiss the silent years between 1965 and 2010 (“one of the strangest and saddest stories in recent literary history”) as David Lodge does on the Op-Ed page of Saturday’s New York Times. Gary Giddins has it right when he calls Salinger’s demise “the most poignant and pregnant literary death since Hemingway.” The key word is “pregnant.” How sad a story will it be if during those years Salinger was planting the seeds of a magnificent harvest? Assuming new books appear in the new decade while his existing work continues to be read and reread, he’ll be as alive to his readers as he ever was or at least no more dead than he was in his exile.

In the Safe

One account from a neighbor in Cornish, N.H., has Salinger claiming that manuscripts for 15 novels are residing in the safe that survived a fire in October 1992. When she was living with Salinger some 38 years ago, Joyce Maynard saw two completed book-length manuscripts and innumerable notebooks. In her memoir, Dream Catcher (Washington Square Press 2000), Salinger’s daughter Margaret referred to the detailed filing system of his writing, with red marks for work that could be published “as is” and blue for copy that needed editing. If the Salinger papers — the product of four decades of resolute, disciplined labor — improve on, equal, further the scope of, or help illuminate the previous installments in the Glass saga, it would surely secure the author’s place in the pantheon of American writers.

Salinger’s last published piece, “Hapworth 16, 1924,” which took up most of the June 19, 1965 issue of The New Yorker, should give readers reason to look forward to the works to come. In the wake of Salinger’s death, however, wide circulation has been given to Jay McInerny’s foolishly worded dismissal of “Hapworth” as “an insane epistolary monologue, virtually shapeless and formless.” McInerny worries that the new material would be “in the same vein.” David Lodge is no less pessimistic. In the aforementioned Op-Ed piece, “The Pre-Postmodernist,” while rightly observing that Salinger’s Glass stories “challenged conventional ways of reading,” he goes on to brand “Hapworth” a failure because Salinger allowed “the pain of hostile criticism to blunt the edge of self-criticism that every good writer must possess.” In fact, what makes “Hapworth” a triumph is that Salinger leaves behind the sometimes excessively coy and self-conscious persona of Buddy Glass to let his fancy and his language fly free in an endless letter from summer camp written by Buddy’s effusive seven-year-old genius brother Seymour.

Read the Daughter

It makes sense somehow that some of the wisest writing about J.D. Salinger and his work would come not from his biographers or critics but from someone who grew up in his domain. Much more than a memoir, Margaret Salinger’s Dream Catcher is an extraordinary study of the man, the father, and the writer. Using his fiction, along with extensive research on the regiment he served with in World War II, numerous other sources, and her own vivid childhood recollections and observations, she shows how the trauma of his combat experience through D-Day, the Battle of the Bulge, and beyond (including his subsequent breakdown) affected his later life and his fiction, whether in uncollected early work like “I’m Crazy,” “The Stranger,” and “Last Day of the Last Furlough,” or in more accomplished short fiction from Nine Stories (1953) such as “For Esmé — with Love and Squalor” and “A Perfect Day for Bananafish,” which ends with a combat-traumatized Seymour Glass putting a bullet through his brain.

Dream Catcher also reveals a rarely stated truth about The Catcher in the Rye (1951), which is that Holden’s famous angst, so often stereotyped as “adolescent” (most recently in Michiko Kakutani’s postmortem), has a darker source. After reading her father’s war stories, the daughter found that “what had semed like foreign territory in The Catcher became, in many ways, a familiar story.” Thus Holden’s view of the world is not merely that of a depressed teenager but of a 30-something man who has experienced the horrors of war first-hand. No biographer can give us what Margaret Salinger does when she observes that “What I was never in doubt about was that my father was a soldier. The stories he told, the clothes he wore, the bend of his nose from where he’d broken it jumping out of a Jeep under sniper fire [according to Buddy Glass, the bend in Seymour’s nose was caused by a baseball bat], his deaf ear from a mortar shell exploding too near, the Jeep he drove… his GI watch, the army surplus water and green cans of emergency supplies we kept in the cellar, the medals he showed my brother and me when we begged him to.”

What makes this section of the memoir so effective is the daughter’s devotion to her mission and her gift for capturing the most expressive moment, for instance the time when at around the age of seven, she was standing by her father “as he stared blankly at the strong backs of our construction crew of local boys, carpenters building the new addition to our house. Their T-shirts were off, their muscles glistening with life and youth in the summer sun. After a long time, he finally came back to life again and spoke to me, or perhaps just out loud to no one in particular, ‘All those big strong boys’ — he shook his head — ’always on the front line, always the first to be killed, wave after wave of them,’ he said, his hand flat, palm out, pushing arc-like waves away from him.”

The Down Side

In spite of the negatives documented in Dream Catcher — the side-effects of living with a driven father whose various strict regimens and unequivocal commitment to writing seemingly overrule all else — Margaret Salinger also reveals elements of character and depth in her father that should give readers reason to look forward to the possible publication of the works he left behind. Sadly, the more repellant images about life chez Salinger that dominate the second half of the memoir are the ones people remember and chatter about. For example, another much quoted item making the rounds in the posthumous aftershock concerns the supposed repudiation of Dream Catcher by Margaret’s brother Matt (who went to Princeton before transferring to Columbia). In a letter to The New York Observer sent soon after the book came out, he writes: “I can’t say with any authority that she is consciously making anything up. I just know that I grew up in a very different house, with two very different parents from those my sister describes.”

His Religion

The wording of the last part of the statement on his death from his agent, Harold Ober Associates, is worth repeating: “Salinger had remarked that he was in this world but not of it. His body is gone but the family hopes that he is still with those he loves, whether they are religious or historical figures, personal friends or fictional characters.”

Fictional characters! In death as in life, he and Buddy and Seymour, Franny and Zooey and Holden, will be together, all in one, creator and creation. So is the door to the world closed even at the end? What about all the people who love Holden? Not to mention the millions who feel that they’re his and the author’s personal friends? No, the door’s not closed and now it never will be. Whether he likes it or not, he’ll be with generation upon generation of readers discovering or rereading the work we have while waiting and hoping for the rest of the story.

Margaret Salinger saves the most telling quote from her father’s fiction for the closing pages of Dream Catcher. Like a typical Salinger character, she gives the stage to her father’s self-confessed alter ego, Buddy Glass, in Seymour: An Introduction, where he quotes a letter from Seymour recalling the time they were both signing up for the draft and Buddy wrote “writer” under profession:

“It sounded like the loveliest euphemism I had ever heard. When was writing ever your profession? It’s never been anything but your religion. Never… Since it is your religion, do you know what you will be asked when you die? But let me tell you first what you won’t be asked. You won’t be asked if you were working on a wonderful, moving piece of writing when you died. You won’t be asked if it was long or short, sad or funny, published or unpublished… I’m so sure you’ll get asked only two questions. Were most of your stars out? Were you busy writing your heart out? If only you knew how easy it would be for you to say yes to both questions.”

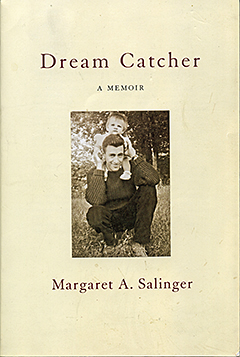

NOTE: The photo of J.D. Salinger (1919-2010) and his daughter, Margaret, is from the cover of her memoir, Dream Catcher. Since she was born in December 1955, my guess is that the picture is from late 1956, around three years after Salinger moved from New York to Cornish, N.H.