|

|

Vol. LXV, No. 8

|

Wednesday, February 23, 2011

|

Picasso’s simultaneous and interrelated work in relief construction, collage, and painting fueled this hybrid style of mischievous substitutions and unexpected combinations.MoMA commentary, “Picasso’s Guitars 1912-1914”

Madness! madness! madness! Men are mad. The scarf of the veil that hangs from the eyelashes of the shutters is wiping the pink clouds on the apple-colored mirror of the sky which is already awakening at your window.Picasso, from Desire: A Play

There’s nothing like the occasional unexpected violation of routine to make life interesting, I always say.

I’m on the New York bus, it’s a rush hour Friday, one of those winter twilights when night happens before you know it, and suddenly all the landmarks of the Lincoln Tunnel approach have vanished. Our driver has been receiving interference-fraught advisories from the dispatcher, something’s amiss, an accident, gridlock at Exit 16, who knows what, maybe something worse, with the tenth anniversary of 9/11 looming.

All I know is everything’s suddenly, brilliantly novel. The lights outlining the Manhattan skyline are being flung into new formations with every sudden, unexpected turn we’re taking, the driver’s discovering the route as he goes along, and so am I, even though I’ve driven it myself many times. When I look for the city, it’s gone. Then it’s back in view, but altered, as if some sculptor of skylines has taken it apart and put it together again. The only building I recognize is the Empire State and it’s veering this way and that like a metronome.

Plunging into the cars-only Holland Tunnel in a Coach America bus is a form of emergency anarchy, and when we come out the other side, our driver seems to have been energized by the derangement of the route, the novelty, the poetry, of it all. He’s grinning like a kid making mischief, to be driving up 10th Avenue from lower Manhattan instead of ramping it directly from Lincoln Tunnel to the Port Authority. Staggering into the northbound pandemonium of Eighth Avenue after two and a half hours on the bus, I’m thinking all I have to do is open my arms, lean back, and I’ll be airborne, such is the energy level on the street.

O Rare Argosy

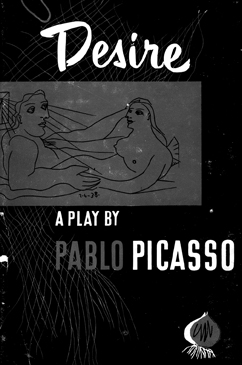

Although art was the theme next morning — our hotel being the site of the College Art Association convention — I had no intention of going to the Museum of Modern Art. My objective was located just off Lexington on 59th Street. At first I was worried. Construction equipment was blocking my view. Could it be that another bookshop refuge had gone the way of the Gotham Book Mart in midtown and Skyline Books in Chelsea? Not to worry. The Argosy abides, looking as plushly cozy and cluttered as it had when I wrote about it four years ago this month (“A Sweet Disorder in the Store,” Feb. 28, 2007). What gems would turn up this time? As always, unsorted books were piled on every flat surface, choice curiosities in each pile, like The Struggles and Adventures of Christopher Tadpole, a hefty Dickensian-looking novel from 1851 by one Albert Smith, with drawings by John Leech, who illustrated the original Christmas Carol. I might have bought it but it was too heavy to lug around the city. I needed something lighter. Near the bottom of an especially tenuously balanced stack I found Picasso’s “first and only literary work,” Desire (originally Le Désir attrapé par la queue), a play written during the German occupation of Paris and published seven years later in an English translation by Bernard Frechtman (The Philosophical Library 1948).

I sat down and looked through the pale blue pages. Priced at $10 ($2.75 in 1948), with a lusty Picasso drawing from 1938 on the cover, the book was, said the liner notes, “a rambunctious farce” for “those who approach life and art without pre-fabricated formulas.” The jacket copy made me think of last night’s rambunctious, un-prefabricated ride, as did a cast of characters that included Big Foot (Le Gros Pied), Onion, Tart, The Two Bow Wows (Les Deux Toutous), Silence, Fat Anguish (L’Angoisse grasse), Skinny Anguish (L’Angoisse maigre), and The Curtains (Les Rideaux). Big Foot was obviously the dominant force, the Picasso of the piece, admired by one of the Anguish sisters as he snores: “He is lovely, like a star. He is a dream painted in water colors on a pearl …. His whole body is filled with the light of a thousand electric bulbs all lit up.”

If there’d been any doubt about my next destination that morning, it was resolved when I came to the passage in which Big Foot Picasso refers to one of his own works, “the maidens of Avignon” better known as Demoiselles d’Avignon, which has been making money (“their annuities”), Picasso writes, “for thirty-three long years.” Originally titled The Brothel and painted in 1907, it was the painter’s breakthrough, his most outrageous statement, shocking and dismaying even sympathetic friends like Apollinaire. Norman Mailer’s 1957 article “An Eye on Picasso,” looks back 50 years to Les Desmoiselles as the “point of departure” when Picasso became “a modern-day Cortez conquering an empire of appearances.”

And it so happened that the breakthrough work could be seen, along with a new show by the conquistador himself, just around the corner (give or take nine blocks) in the greatest city in the world.

Beyond Guitars

In the new MoMA exhibition, “Picasso’s Guitars 1912-1914,” which will be on view until June 6, Apollinaire is quoted in reference to “these strange, coarse, and mismatched materials” while an art critic of the time, André Salmon, describes people “shocked by the things that they saw covering the walls, and that they refused to call them paintings because they were made of oilcloth, wrapping paper, and newspaper.” While Picasso’s guitars, with their muted tones, may seem tame compared to his Desmoiselles, what he was doing to received notions of painting was no less revolutionary. Why limit yourself to paints and canvas when you can tear off strips of your own wallpaper and affix a fragmented newspaper headline hinting at the advent of the Great War? And who cares if in a distant era the grand finale for Pete Townsend of the Who was the ritual destruction of his guitar? So what if Jimi Hendrix played his Fender Strat with his teeth, set it on fire, and reinvented the Star Spangled Banner on it? Fifty years before the psychedelic sixties, Picasso was destroying the accepted perception of the guitar and reinventing the instrument in his own image — or rather, in the image of his desire, for, as Norman Mailer observed in “An Eye on Picasso,” a Picasso guitar is “hips, a waist, and the breast; it is a torso; it is a woman … it is the curve of two lovers in the act, it is the act, it is creation.”

An hour later, up on MoMA’s fifth floor, gazing at the naked-pinkness-embedded-in-blue-ice effect of the Desmoiselles d’Avignon, two maids staring out, two darkly masked, one darkly looking elsewhere, I’m thinking of Big Foot and his harem. and of Mailer’s conquering warrior, and how when “the grand old painter” died in 1975, Paul McCartney honored him with a song, “Picasso’s Last Words” — “Drink to me, drink to my health/You know I can’t drink any more.”

Maybe not, but he can play. He’s playing right now at the Museum of Modern Art, and given the ways of the world from time immemorial, what other artist equals or surpasses him as an irreverent deity playing fast and loose with the stuff of life, its mischievous substitutions and unexpected combinations?