| NEWS |

| |

| FEATURES |

| ENTERTAINMENT |

| COLUMNS |

| CONTACT US |

| HOW TO SUBMIT |

| BACK ISSUES |

caption: |

A Carnival of Images: America Loud and Clear

Stuart Mitchner

There are exhibits and there are shows. Both words work well enough, and to avoid repetition a reviewer can employ either one. But when a museum presents a group of works as stunning as "American Photorealism," which opened December 12 in the Voorhees Special Exhibition Galleries at the Zimmerli, "show" is the word. "Exhibit" is too formal a term for this carnival of American images.

The show begins with Richard Estes's Waverly Place (oil on canvas, 1980), an almost seven-foot-wide panorama of an intersection in Greenwich Village that will seem familiar to anyone who knows the area. If you connect with this specific portion of Manhattan, you'll probably go through a whole sequence of calculations as you try to locate it. You're looking north on Seventh Avenue South on a bright, clear day. You can trust that much because of the location of the jazz club, the Village Vanguard, and because the parked cars are pointing south. As for traffic, there is none. Usually the street is roaring with four or five lanes of southbound cars, trucks, busses, and taxis. You may also wonder at the absence of midtown towers in the distance. Either the artist has eliminated the Empire State Building or you have forgotten that it can't be seen from this vantage point. The emptiness of the street forces you to focus on the buildings, which are presented in crisply photographic detail. The two-story building on the island projecting into the intersection suggests the prow of a ship. The street intersecting with Seventh Avenue is also empty of traffic. A study guide for teachers I found online imagined "an unnatural hush" descending on the scene ("Estes's empty cityscapes evoke feelings of estrangement and isolation") and suggested a series of study questions that all but coaxed students to see it the same way. "Can you find any people in this painting? Where do you think they all might have gone? Imagine you are standing in this intersection. How would you feel about being there? Is it a busy, exciting city or a lonely, desolate place?"

I already knew which busy, exciting city it was, and when I stood in the intersection at the entrance to the gallery, I saw nothing ominous in the absence of people and traffic. I was too involved in guessing at some of the more subtle liberties the artist had taken with this slice of reality ‹ such as the fire hydrant in the left foreground, which has more to do with brush strokes than camera work, and the unreal liquidity of the pavement, the streets flowing together like two rivers of grey paint. It seems reasonable to assume that the artist left out traffic and people not necessarily because he wanted to evoke "a lonely, desolate place" but in order to remove the distractions that ordinarily get between the viewer and the naked, physical essence of the scene. Chances are he may even have had a fondness for the spot and simply wanted to set it forth with heightened clarity.

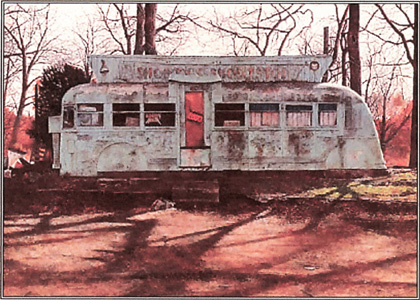

Odd as it seems, artworks with a photographic basis appear particularly unsuited to reproduction in a newspaper. The photo of John Baeder's 1984 oil on canvas, Shorty's Shortstop, accompanies this review instead of Waverly Place because less of it is lost in translation to black and white. In its original incarnation as a bus, this abandoned diner was white. When asked what fictional elements he had added to his subject, the artist, who lives outside Nashville, Tennessee, provided some interesting background information that suggests how arbitrary the "realism" in "photorealism" can be. He admitted having added "a few elements to the image," changing the color from "a very weathered white" to something more on the "landlord green" side. It was his "fantasy" to turn it into a diner based on "an A- frame drive-up hamburger, hot dog, ice cream roadside joint somewhere in the innards of west New Jersey." There was no "Shorty's Shortstop," in fact; it was named for and in homage to a dog ("a most marvelous, loving Australian shepherd") who would come into the studio while Baeder was working on the painting and sit "very protectively" by the easel. One of the compelling qualities of the painting is how thoroughly and intricately the painter has covered the abandoned diner with the abusive effects of time and weather, as well as adding some graffiti, which he says were actually drawn on "an old closed-up forever" Dairy Queen in Clark, New Jersey. Although you'll have to go to the Zimmerli to see these details, the graffiti originally depicted a chef and a dog. When he redrew them, he meant the chef to be the proprietor of his fantasy diner and the dog a sketch of the real-life Shorty. And the bus that began it all? It was located in Tennessee.

Most of this show's "photographic" pieces probably underwent no less complicated and no less "fictional" evolutions. These works don't serve realism; they take possession of it. Most of the artists here are playing fast and loose with reality, amplifying it, heightening it, exploiting it, and exploring it. When you stand before works like Linda Bacon's Big Strike, you might be Gulliver in the land of the giants, dwarfed by the super-real, super-sized equipment of Brobdingnagian fishermen. The oil on linen Sweet Man Blues, is another Bacon still-life of hallucinatory dimensions dominated by the Ethel Waters recording on Black Swan that gave the picture its title; a B.B. King poster; a seemingly larger-than-life guitar; and a pair of red high-heeled sandals fit for a dancing girl in Brobdingnag. You don't stand outside these images; they want to take you in. The same thing is true of Charles Bell's larger than life pinball machine playing surface in Finis Coronat Opus with its brilliant red runways and golden point-lights like the dream landscape of a compulsive player who goes to sleep with the sound of pinball bells ringing in his ears.

Another impressively hallucinatory work is David Parrish's Happy Birthday Baby, which would be a riveting contribution to any show of Pop Art. Again the scale is a travesty of reality, with two immense masks on either side of a super-real Elvis Presley doing the bump and grind that put fear in the hearts of American parents in the late 1950s. One mask may be Marilyn Monroe; the other looks dark and satanic, with a twisted mouth. The performance is apparently being conducted by a valentine heart with Mickey Mouse hands.

Photorealism, where art thou? In Tom Blackwell's display window in Swim Wear perhaps? Not if you look closely. Those two women in bathing suits, one recumbent, one with hips sexily thrust out, are no mere department store dummies. The so-called real world outside the window is actually painted into it, the image of a parked car not reflected but imposed on the recumbent bather, the leaves on trees on a New York street not reflected but embedded in the element of another dimension. The work is oil on masonite, which no doubt helps create the effect of merged dimensions. Yet another version of reality ‹ you could say it represents the "real" reality ‹ is occupied by the woman standing in front of the window, intently focused on her own concerns and oblivious to the phenomena haunting the work of art that is the window.

This is a democracy of imagery, all shapes and sizes and degrees of exactitude. You have horses and kids, swimming pools, coffee cups, pottery, plastic ketchup bottles, Harley Davidsons, Super Duper weenie trucks, small town street scenes, wrecked cars, lingerie, salvage yards, waterfalls, nudes holding Messerschmitts, fabrics, Deco glassware. You can see truly amazing panoramas like Anthony Brunelli's Hanoi Market (oil on linen) with landscapes of crockery on either side, clear daylight illuminating one tumbled, sloping range of porcelain, the other in shadows, behind which are still deeper darker shadows. One of the most purely beautiful works in the show is Kim Mendenhall's oil on linen, To: Harnett, which is dedicated to William Harnett (1848-1892), a key figure in the history of American still-life painting.

Several less exciting works are a better fit with the least imaginative definition of photorealism, which may explain why they were chosen for the Zimmerli's introductory brochure. Jack Mendenhall's Miami Beach could be illustrating an advertisement for the department of tourism. Yellow Porsche is one of the less striking works by Ron Kleeman, who takes you inside the world of an engine in Mr. Gasket and claims his paintings are "a fist tattooed with the word 'HERE' across the knuckles." Randy Dudley's Railroad Bridge-Joliet, Illinois is handsome enough, but as an act of imagination, it falls short of the exhibit's more dazzling show-stoppers.

"American Photorealism" runs through March 27, 2005. The Zimmerli is located at 71 Hamilton Street on the Rutgers University campus in New Brunswick. You can park free in the hilltop lot adjacent to Kirkpatrick Chapel, from which the view of the surrounding area will be even more striking when you come to it with your eyes full of the sights and sounds in the Voorhees Galleries. For more details, call the museum at (737) 932-7237 or visit it online at www.zimmerlimuseum.rutgers.edu.