|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 3

|

|

Wednesday, January 16, 2008

|

|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 3

|

|

Wednesday, January 16, 2008

|

|

“I used to take the whole canon with me to the beginning of each film, and fight for Doyle…. Then Granada Studios stepped in and gave me two weeks rehearsal instead of the one. So the first week I could fight for Doyle and the second week I could work with my fellow actors.”Jeremy Brett in 1991

After reading The Great Gatsby, Holden Caulfield wants to call Scott Fitzgerald on the phone. After watching Jeremy Brett’s performance as Sherlock Holmes in the Granada television series that spanned a decade, you want to knock on his door, shake his hand, maybe give him a hug. That he should die in 1995 with several episodes still to be filmed makes a kind of poignant sense because one thing that makes his Holmes so superlative is that he plays the part as if his life depended on it. Like a male Sheherazade who knows he has to tell his story well or else, he seems driven to keep outdoing himself to earn one more night among the living. He was only 61 when he died; he’d played Holmes in 41 episodes with some time off to repeat the role onstage in 1988-89. This extraordinary series of films is now available in its entirety in a six volume, 12-disc DVD set at the Princeton Public Library.

Incredibly, Brett was never officially honored for his virtually unprecedented accomplishment. He deserved an Order of the British Empire (OBE) if only for working so hard to see that justice was done to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s original intentions. As he put it in the interview quoted above, he had to “fight for Doyle.”

The Sherlock Holmes industry produces new books every year, making Christmas shopping easy if you know someone whose fantasy life includes digs at Baker Street. According to one account, there are 4,000 such books, two relatively recent ones being Caleb Carr’s The Italian Secretary (2005) and Michael Chabon’s The Final Solution (2004). The Guiness Book of World Records lists Holmes as the most portrayed character in history, over 70 actors in over 200 films, a list that may not even include the title character in the popular television series, House, M.D., where the title character (House a play on Holmes) lives in apartment 221b and has an assistant named Dr. James Wilson.

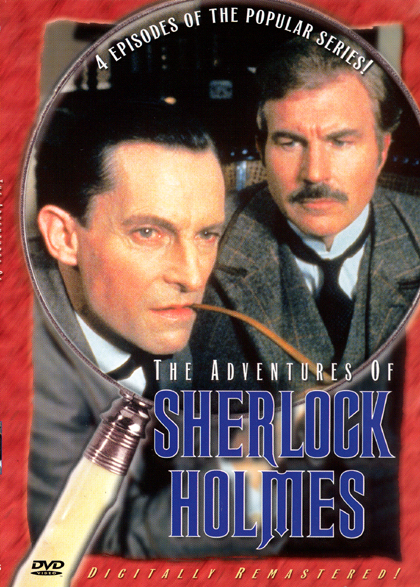

Jeremy Brett in Action

Actors who have taken a turn as the master detective range from John Barrymore to Michael Caine, but the accepted standard is Basil Rathbone, who played the role 15 times in motion pictures and on television between 1939 and 1953. “Played” isn’t really the word for it. You have only to look at Rathbone’s severe, angular countenance to know that he was born for the part. Because he is so absolutely the official (and superficial) template of the character, he doesn’t need to do much more than go through the paces. While Sherlockians find it hard to complain about Rathbone, however, most of them have serious problems with Nigel Bruce’s bumptious Dr. Watson.

One great accomplishment of the Granada series is the restoration of an intelligent, forceful Watson, as played by David Burke in the first 13 episodes and Edward Hardwicke in the remaining 25. But if Granada’s Watson can be called a restoration, Jeremy Brett’s Holmes is a revelation. His vitality is phenomenal. The arrogant energy he projects would have had poor Nigel Bruce in tears. He once had to defend the intensity of his interpretation to the author’s daughter, Dame Jean Conan Doyle. As he explained in an interview, “I had to hide an awful lot of me, and in so doing I think I look quite often brusque, or maybe sometimes even slightly rude. In fact Doyle’s daughter … did once say to me, ‘I don’t think my father meant You-Know-Who to be quite so rude’, and I said, ‘I’m terribly sorry, Dame Jean, I’m just trying to hide me.’”

Watch Brett in action and you’re glad he hid his personal charm as well as he did (from all accounts, he was a lovable and loving man). His Holmes prefers to leap over chairs rather than walk around them. The force he brings to the part is dark, edgy, sometimes reckless. Brett was clinically bipolar, and while it would be an insult to his talent to assume that the illness helped make his Holmes so mercurial and unpredictable, there’s no doubt that, as Conan Doyle describes him, the great detective endures dark lows and manic highs. Thus the cocaine and the smoking (Brett had a three-pack-a-day habit he found devious ways to indulge during the filming).

Unlike the cold, analytical Holmes embodied by Basil Rathbone, Brett’s is passionately, warmly alive. The warmth is doubtlessly his essential humanity shining through the neurotic trappings. He’s playing a man who is notoriously closed, yet you can see him feeding on his own intelligence when the essence of a problem possesses him; it’s the hectic fever in his eyes and the play of nerves and muscles in his face, especially in the odd, twitching half-smiles that are among his rare flashes of civility. To understand the wildness he brings to the role, think of a less murderous Mr. Hyde. His Holmes storms around the flat at 221b Baker Street like a caged tiger; you can almost see the walls shaking. His “filing system” is a masterpiece of mad-genius chaos. He flings his papers about in a fury, leaving the mess for the steadfast, often exasperated housekeeper Mrs. Hudson (Rosalie Williams) to clean up.

Brett’s random, often seemingly involuntary gambits make his quiet moments all the more moving. A talented singer who was told early in his career that he could be an opera tenor if he dedicated himself to it, he has the power to send his voice to the depths of the balcony with ease, to bully and intimidate at the top of his bent, and then come beautifully down to earth as he does at the end of the episode titled “The Second Stain.” Having been congratulated in uncharacteristically heartfelt terms by Inspector Lestrade of Scotland Yard (Colin Jeavons) after a particularly miraculous feat of detective work (he has just saved England, in effect), he drops in the space of a heartbeat from a ringing, typically imperious acknowledgment of the compliment to a humbled, barely audible “Thank you.”

It’s hard to imagine any actor surpassing or even matching what Brett accomplished in these 41 episodes. I haven’t seen the Holmes played by the Russian actor, Vasili Livanov, whose work earned him an OBE, but my guess is his was a more contained, less extreme portrayal, one less likely to offend the Queen’s sensibilities. Again, it seems a crime that Brett never received the formal recognition he deserved.

It’s worth repeating the invaluable contribution of Burke and Hardwicke in bringing Dr. Watson to life as Doyle intended him: a man whose skills as a physician, pugilist, and documentarian are indispensable to his difficult, fascinating, and ultimately beloved friend. Brett considers that relationship one of the glories of the series: “To me, the Sherlock Holmes stories are about a great friendship. Without Watson, Holmes might well have burnt out on cocaine long ago. I hope the series shows how important friendship is.”

The Down Side

Having watched all but the last few episodes, I should point out that there were times when the commercial powers-that-be trumped Jeremy Brett’s dedication to the integrity of the source. No doubt the occasional heavyhanded, florid, and sometimes downright ludicrous impositions on Doyle’s storyline were due to the immense popularity of the series. Whenever a full-length television “special” was called for, the producers simply picked the most exploitable stories, padding them with bogus scenes and invented situations. Even in some of the best of the shorter episodes, the situation verges on cliché whenever it strays too far from Holmes and Watson and Baker Street. The most egregious examples come in the 1990s with bloated travesties such as “The Three Gables” and “The Master Blackmailer.” Not to end on a negative, here are some personal favorites: “The Naval Treaty,” “The Copper Beeches,” “The Second Stain,” “The Devil’s Foot,” “The Man with the Twisted Lip,” “The Dying Detective,” and “The Illustrious Client.”

The set of the Granada Sherlock Holmes now available at the library (791.45 SHE, volumes 1 through 6) has been remastered, bringing out the original brilliance of the production values. The attention to detail is admirable, with locations and landscapes stunning enough to serve as commercials for England’s Department of Tourism. The carriages and hackneys and period trains are especially beautiful to behold. The final volume’s special features include an interview with Edward Hardwicke, a tour of a reconstructed to the last detail Baker Street with Adrian Conan Doyle (the author’s son), and a conversation with Jeremy Brett and Edward Hardwicke.

Finally, to appreciate how eternally grateful to Granada we should be, consider the television work Jeremy Brett was doing prior to taking on Sherlock Holmes: The Love Boat, Galactica 1980, Hart to Hart, The Incredible Hulk, and Young Dan’l Boone. Granada gave a great actor the role of a lifetime.