|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 3

|

|

Wednesday, January 20, 2010

|

|

To put it bluntly, I have to admit that I do not like music. I try very hard to eliminate it from my life and from my films …. Music, for me, is only bearable if you listen to it with the maximum attention, both with mind and body.Eric Rohmer, Preface to De Mozart en Beethoven

I was in the kitchen doing the dishes with Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 turned up loud on the Bose Wave when my wife came in to tell me that Eric Rohmer had died. I didn’t want to hear about anybody dying, so I made dismissive motions with the plate I was holding, not now, no death, sorry, not while Mozart’s “pouring forth his soul in an ecstasy.” It’s a wonder I didn’t drop the plate.

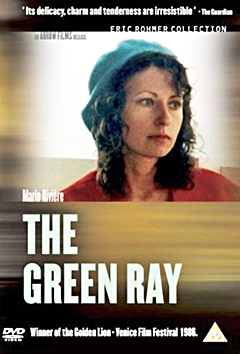

Listen to the andante of the 40th with “maximum attention, both mind and body” after watching the closing moment of Le rayon vert (1986) and Rohmer and Mozart go together as seamlessly as sunset and sky. When Marie Rivière’s benighted Delphine sees the line of green flash on the horizon and knows that after suffering confusion and heartache she’s finally at one with her feelings and the world, it’s a Mozart moment.

I know, how dare I speak of Mozart in the same breath with a mere film? Summer, as it was called when it came out here, sounds hopelessly banal: a Parisian stenographer who can’t seem to fit in looks for love on her summer vacation only to be disappointed and discomfited at every turn. In fact, I’d been so disappointed and discomfited by the banality of Rohmer’s previous film, Full Moon in Paris (1984), I was beginning to associate his work with the tedium of watching photogenic young French things frolic in and out of pointless affairs. I was in danger of becoming a Francophobe. Not so in Summer, thanks to Rohmer’s pitch-perfect direction, and, most of all, thanks to Marie Rivière’s unforgettable performance, much of which was clearly improvised (she shares screenplay credit with Rohmer). The scene where she, the only vegetarian at a table of carnivores, gamely explains and defends her aversion to meat in an atmosphere of toxic civility makes your heart ache, even if you’re a meat-eater. Rivière’s uncannily expressive attempts to articulate her feelings will have you pulling for her, and when Delphine has her lovely moment at the end, you find yourself sharing it.

The other film that restored my faith in Rohmer was Le beau mariage (1982), which I saw on video some five years after it came out. Once again the story line doesn’t promise much. A headstrong young woman (Béatrice Romand) decides she’s going to get married, sets her sights on a husband, and is humiliated. As before, what saves the day and has you thinking of Jane Austen instead of a grade B Françoise Sagan is Rohmer’s direction and the actress who gains an emotional hold on you by becoming touchingly human around the time you were half-hoping she’d fail in her plot (if only because her intended target was so clearly unworthy of her).

It’s fairly simple when you come right down to it: Rohmer’s characters are at their best when they’re uncomfortable and when issues like making more than superficial contact with other people are taken to a level where art transcends entertainment — which is when you may begin thinking of Jane Austen and Mozart.

In what is his most accomplished later work of the ones I’ve seen, Autumn Tale (1999), Rohmer brings Marie Rivière and Béatrice Romand together as middle-aged best friends Isabelle and Magali, except that on this occasion the confident winner at home in the world is played by Rivière, whose black hair has gone gold, and the misfit is played by Romand, whose frizzy hair has achieved formidable Afro-style dimensions. This time a male (Alain Libolt) is the portrayer of maximum discomfiture, having answered an ad placed by Isabelle, who wants to find “a nice man” for Magali. Even more than in Le beau mariage you find yourself thinking of Jane Austen, and no wonder, when Rohmer puts in play a series of matchmaking machinations and complications (including a second matchmaker working on Magali’s behalf) beyond even Emma’s wildest dreams. Bidolt touches every nuance of the situation perfectly, ready to fall for Isabelle, who is subbing for Magali without telling him. So you have two people to pull for and suddenly that silly match means much more than it should.

Maud and Garance

Most of the eulogies since Eric Rohmer’s death January 11 at the age of 89 tie his creative identity to his dialogue, and while the Rohmer aesthetic is nothing if not conversational, what also truly and fortuitously absorbs him is the opposite of poised, articulate, intellectual, philosophical communication. Moviegoers around the world discovered this aspect of his work through Jean-Louis Trintignant in Ma Nuit Chez Maud (1968), Rohmer’s breakthrough film. The director himself has said that “fidelity” is a major theme in his moral tales, but what makes the tension in Maud fascinating is the way he explores a situation that in lesser hands would seem little more than an overblown erotic tease, a shaggy Maud story. Surely anyone in the audience — male or female, young or old — beholding the supremely beautiful, desirable, womanly Françoise Fabian as Maud, naked under the sheets, waiting and apparently willing, will roll their eyes at the idea that Jean-Louis is going to pass the night chastely wrapped in a coverlet. Even after he finally crawls onto the bed next to her, he stays on top of the covers. And when he finally does make a move, it’s too late. “I don’t like people who don’t know their own minds,” she tells him as she scurries into the bathroom.

Like it or not, Jean-Louis is us, the viewer. Regardless of gender, we’re on his side. He’s spending the night with a woman he’s just met. She’s invited him in order to save him a long drive home on icy, hilly roads. He’s painfully civil and polite and understandably wary. He also has eyes for a pretty blonde he sees at mass (Marie Christine Barrault) and has been working up the nerve to approach, so you could excuse his hesitance as a rehearsal of fidelity. But not after the extended sequence where the camera moves in medium-close to Maud as she’s telling him about her life with her husband and his death (an auto accident, one good reason for inviting Jean-Louis to stay the night). Of all the many wondrously seductive women in French film, the one who most resembles Fabian here is Arletty as Garance in Marcel Carné’s Les enfants du paradis (1945).

I doubt that anyone summing up the career of Eric Rohmer has spoken of it in terms of romance or romanticism, but it’s impossible to think of anything else when you’re chez Maud admiring Fabian with visions of Garance dancing in your head. In the first act of Les enfants there they stand in a room with a bed: Garance, the glory of the Boulevard du Crime, and Baptiste, the genius mime who has performed transcendent feats that day. As played by Jean-Louis Barrault (Marie-Christine’s uncle), Baptiste seems an almost supernatural being, and when Garance begins unbuttoning her blouse, the magical night appears to be coming to its anticipated consummation. Instead, like Jean-Louis in Maud, Baptiste misses his chance, backs off, walks away, and regrets it the rest of his life.

Rohmer’s Jean-Louis doesn’t seem to regret missing his moment with Maud. Inspired by her remark about “people who don’t know their own mind,” he finally approaches the blonde Catholic and — after a spending-the-night-together scene as nicely done in its way as the one with Maud — marries her. Several years later, as the film ends, he encounters Maud, introduces her to his wife and little boy, and as she goes her way and he goes his, hand in hand for a swim with wife and child, you’re witness to the two sides of Eric Rohmer. The complicated character sadly exits while the happy-ending little family goes to the beach.