|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 4

|

|

Wednesday, January 23, 2008

|

|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 4

|

|

Wednesday, January 23, 2008

|

|

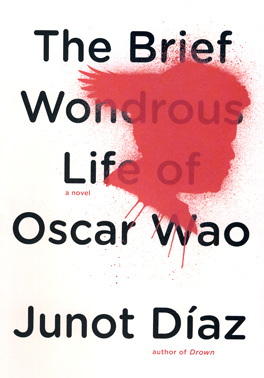

In an interview about The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (Riverhead $24.95) provided by the publisher, Junot Díaz says, “I knew this novel would live or die on its female characters.”

Oscar Wao not only lives on its female characters, it achieves literary splendor through its depiction of Oscar’s mother and sister, Beli and Lola, and the way they talk, think, and deal with adversity, most of it courtesy of the Dominican dictator, Trujillo.

First Things First

You can tell something’s up as soon as you read the first of the book’s 33 footnotes, which begins “For those of you who missed your mandatory two seconds of Dominican history” and goes on from there, clearly not one of your typical academic asides. Like the narrative proper, these informational outbursts are gutsy, profane, and in-your-face and have little in common with the cover-all-bases putterings of the diligent scholar/critic. Powered by a mixture of pure Jersey energy and Dominican lore, the notes tell you all you need or want to know about Trujillo and his ruthless reign. Instead of distracting from the narrative or distancing you from it, they give it documentary heft without diluting the flavor of the surrounding prose. The broader context created by the notes also makes it easier to accept the relatively crass and superficial style of Yunior, the homeboy narrator of Oscar’s tale of woe (Oscar Woe, it could be). There are times when Yunior’s flip, callous voice almost tests the integrity of the novel, which can swing from street talk and jive to great writing in a matter of pages, or even in the same paragraph. Every now and then when you’re least expecting it, you may recognize the abiding presence of an author who also happens to be a tenured professor at M.I.T. The encompassing intelligence is there in the opening seven pages as Díaz sets the stage. Chapter One (“Ghetto Nerd at the End of the World”), however, would seem to belong to a thinner, less ambitious work, a tale told by a sexist, macho Dominican-American college boy more or less at the expense of his hapless, horny, sci-fi/fantasy buff roommate Oscar. But when Oscar’s sister Lola temporarily takes over the narrative in Chapter Two (“Wildwood”), you’re on your way into the heart of a very special work of fiction.

Containing Multitudes

According to the author, to “get close to describing what’s happening in the New World” you need “every narrative strand you can muster.” You also need a prose style capacious enough to contain not only ’80s urban hip-hop and MTV-contemporary but a literary consciousness that spans genres and periods from the House of Atreus to Tolkien to Planet of the Apes and “that could be top-level hilarious and top-level heartbreaking…that could be hip about the present yet also render the past not as something dead or shackled inside sepia tones but as something dynamic, with all its confusons, excitements. disappointments, and energies intact.” The book’s range is evident in its two epigraphs, one from Marvel Comics (Fantastic Four) and the other a passage from Derek Walcott that ends “either I’m nobody or I’m a nation.” Describing his novel’s unlikely genesis, Díaz says it came “after a night of partying” in Mexico City: “I picked up a copy of The Importance of Being Earnest, and I said Oscar Wilde’s name in Dominican and it came out ‘Oscar Wao.’ A quick joke, but the name stayed with me, and next thing you know, I had this vision of a poor, doomed ghetto nerd.”

Oscar’s Revelation

Seen primarily through the eyes of his street smart friend Yunior, Oscar Wao is treated with what might be called backhanded sympathy, or tough love, more a figure of ridicule than the “hero” referred to on the book jacket. He’s fat, weak, a loser with girls, the nerdy opposite of the macho Dominican stereotype. As a sci-fi fantasy fanatic, he does some writing himself in that genre with no more apparent success than he has with the opposite sex. The truly “wondrous” part of his brief life comes at the end of it, much the same as the “happy” part of Francis Macomber’s life does in the Hemingway story Díaz’s title brings to mind. The protagonist in “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” dies the moment he comes into his own facing down danger. Oscar’s fate is different in that he’s facing certain death for the sake of love; his mad, sublime, against-all-odds tenacity surpasses macho clichés of bravery and achieves its own absurd magnificence. Díaz ends his book celebrating Oscar’s revelation with a quote from his last letter in which he reveals that he’d finally experienced intimacy with a woman after being a virgin all his life: “So this is what everybody’s always talking about! Diablo! If only I’d known. The beauty! The beauty!”

It’s “The horror! The horror!” in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. In the sugar-cane-field killing grounds of Díaz’s Dominican heart of darkness, literature lifts the rock the horrors of the Trujillo era are buried under, shows you the brutality and tyranny in painful detail, and then endows it with the glory of art, thus “The beauty! The Beauty!”

Oscar’s Limitations

If Oscar had been as fully felt and realized a character as Lola and Beli, the last chapters of the novel would be even better than they are. But then perhaps there was no way his ordeal in the cane fields could have been as powerful and harrowing as the earlier account of the beating endured there by his mother, Beli, as a young woman. The tone of Yunior’s account of Oscar, with its mixture of affection and exasperation, comes at the expense of a deeper identification with the character. Until that ultimate act of love, Oscar never quite escapes the terms of the author’s original vision of the “poor, doomed ghetto nerd.”

Now that The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao has apparently been sold to Hollywood, you can be sure that whoever films it is going to take full advantage of the violence of the cane field scenes. Unfortunately, I doubt that there is a director on the planet capable of adapting those scenes in the spirit with which they’re written or of passing up the opportunity to add another orgy of movie violence to the endless list. Here’s where literature does what film can’t do. As brutal and graphic as these scenes are, the violence is taken to another level because of the energy and excitement of inspired writing. You can almost feel Díaz coming into his own as a novelist in the passage where Beli is the victim. It’s not just the sense that this writer has discovered his genius but that he’s accomplishing a noble mission — to exorcise the evil of Trujillo’s reign of terror by making literature of it.

When Oscar is the victim, however, there’s a carry-over of the shallower tone that has dogged him from the beginning, as if he were still the hapless nerd suffering the first blows of the doom the title has led us to expect. The author seems to be writing more about a bloodless idea than a living, bleeding human being when he puts this analogy into play: “It was like one of those nightmare eight-a.m. MLA panels: endless.” It seems a strange move, to say the least, when the usurper of academic documentation who’s been speaking a homeboy patois invokes the Modern Language Association convention as his protagonist is being viciously beaten.

“Little Junot”

Once upon a time in the early 1990s when Rutgers University Press was located in a former men’s clothing store on Church Street in downtown New Brunswick, my wife used to come home talking about a student intern she was particularly fond of, often using the adjective “little” in reference to him, even though he was probably a head taller than she was. Student helpers at the Press were occasionally talked about at home because they were either writing stories or books or painting or dancing or singing in punk rock groups. Hearing that this particular intern had actually sent some of his stories to the New Yorker, most literary-worldly folk think “Ho, lots of luck, kid” and then smile when they hear that the impatient young author had the nerve to bug the fiction editor when a response was slow in coming. Not amused, the editor rejected the stories, no surprise. Not long afterward the New Yorker hired a new fiction editor and next thing we heard was that “little Junot” had a story in the December 25, 1995 issue. With more to come. In one of those rags to riches tales almost too good to be true, the obscure Rutgers intern was soon being hailed as one of best young writers in America. In 1996 his first book, Drown, came out to great acclaim, and now The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao is getting raves from Michiko Kakutani and Time, among many others, not to mention that it’s just been nominated for a National Critics Circle award.

In the interview quoted above, Díaz describes his “imaginary audience”: “I just happen to believe that folks of all cultures and colors, and grad school types and immigrants and…people who love to read and fanboys and fangirls and love-story addicts and lit heads and homeboys and homegirls and history buffs and activist and family epic lovers and nerds…can all sit in the same room together and blab usefully to one another. I’m idealistic that way.”

If you visit YouTube you can see Junot Díaz read from his work and answer questions from the audience at Google’s Mountain View, California headquarters; the event took place September 26, 2007, as part of the Authors@Google Series.