|

|

Vol. LXV, No. 4

|

Wednesday, January 26, 2011

|

“I am an amateur reader.”Kenneth Slawenski

J.D. Salinger died a year ago tomorrow, a little less than a month after his 91st birthday and 47 years after the publication of his last book, Raise High the Roofbeam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction (Little Brown 1963), which he dedicated to his wife and children and “an amateur reader, or anyone who just reads and runs.” Presumably he was imagining a reader without a professional agenda, someone true to the primary definition of amateur — “somebody who does or takes part in something for pleasure rather than for pay.”

Two readers, neither of whom qualifies as an amateur, have attempted to scale Mt. Salinger. In 1988, Ian Hamilton, author of a biography of Robert Lowell and numerous reviews and essays, hardly left the base camp before litigious thunder from on high drove him into the shelter of his tent, where he proceeded to write a mean-spirited account of his failed quest. In 1999 Paul Alexander, a former reporter for Time with biographies of Sylvia Plath and James Dean to his credit, had a more positive attitude but lacked both the stamina and the requisite equipment and had to turn back miles short of the summit.

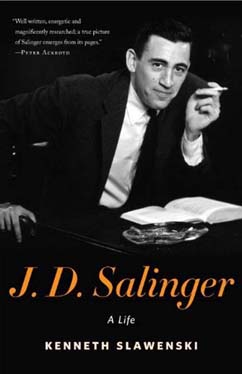

Kenneth Slawenski came to the challenge from cyberspace. When he says, “I am an amateur reader,” he speaks from the confines of his website, called Dead Caulfields, which he established in 2004 and has been mysteriously maintaining, its commentator, curator, and archivist, masking his identity by becoming, in effect, a Dead Caulfield. In that sense, he’s been as elusive and reclusive as his subject — or was until he put his name to the biography, J.D. Salinger: A Life (Random House $27). Up to now he’s been broadcasting on what could be called an “amateur reader” wavelength, a concept Salinger himself might appreciate, with his fondness for talismanic, left-field communications (ancient letters, poems written on a baseball mitt, soul-saving phone calls from someone pretending to be someone else). However sophisticated, attractive, and informative it may be, Slawenski’s website is more like a cottage industry than a bastion of literary professionalism. It’s evident that he began the biography as he began the website, for pleasure not for pay (the profit ensured by the recent Book of the Month Club selection being a stroke of good fortune he probably never anticipated), and you’ll find no trace of him in the Lit Chat sideshow Salinger loathed. Nor does he have the aroma of the academy about him. While he may well get pounded by jaded pedants for his lack of professional polish, he makes his points and gets his message across effectively enough to satisfy a pro like Peter Ackroyd, who found the book “well-written, energetic and magnificently researched.” A review in The Spectator pointed out the “love and zest” with which he “sets about his task.” Needless to say, “love and zest” come in handy when you’re climbing metaphorical mountains. But Slawenski had something else. He found another way, a route that worked for him and that no one else knew about. He didn’t climb, he burrowed. It took him eight years and when he came out he was close enough to wave to the mist-shrouded figure at the top. The big question is, Did the apparition wave back? Does he have something to show us? What’s that bulky object in his other hand?

Becoming a Caulfield

Of course there’s good reason to suppose that Salinger would be appalled at the liberties this “amateur reader” has taken with the material of his life, particularly his early fiction, whether unpublished or still in manuscript. “Magnificently researched” doesn’t begin to describe a labor of love on this scale. Far from reading and running, the intrepid biographer tracked down every page of Salinger’s writing he could find, scouring the archives in Firestone’s Special Collections, in New York at the Public Library and the Morgan Library, and at the Ransom Center at the University of Texas. The path was fairly well traveled, Hamilton and Alexander, among others, having been there too, but they never dug this deeply. Kenneth Slawenski immersed himself in the material, absorbed it, studied it, conceptualized it, and symbolically inhabited it by creating a website named for Salinger’s characters, one of whom, Kenneth Caulfield (later known as Holden’s dead brother Allie), shares the biographer’s first name.

Staking His Claim

The first thing you see when you access the Dead Caulfields, which I recommend to anyone reading J.D. Salinger: A Life, is a resplendent, almost surreally idyllic full-color postcard-size view of towers overlooking Central Park with trees and lake in the foreground. There’s a timeless, painterly quality about the image, a hint of fairytale magic in the way light catches the surface of the water and in the stillness of the two children on the shore. Right away you know the creator of the site is in synch with his subject, for if anyone has taken literary possesson of this scene it’s Salinger. He owns the park and the carousel and the Natural History Museum (even John Lennon’s Strawberry Fields memorial lies in Salinger’s shadow, given the killer’s twisted association with Holden Caulfield). Staking his claim to all this Manhattan real estate (not to mention Radio City Music Hall and the Rockefeller Center skating rink) in The Catcher in the Rye, he extended his reach in “Zooey,” “Raise High the Roofbeam, Carpenters,” and “Seymour: An Introduction.” In spite of living the last 50 years of his life in New Hampshire, Salinger was, is, and will forever be a New Yorker, a connection underlined by his special relationship with the magazine of the same name.

War

Paul Alexander’s biography spends only 20 pages on Salinger’s experience with the 4th Infantry Division in World War II, Hamilton’s even less, while Slawenski rightly comprehends the impact of the war on the work, devoting close to 80 pages to exploring that dynamic, the core of it in chapters titled “Displacement,” “Hell,” and “Purgatory.” Imagining Salinger’s state of mind on completing The Catcher in the Rye in the autumn of 1950, he writes: “Holden Caulfield, and the pages that contained him, had been the author’s constant companion for most of his adult years. Those pages were so precious to Salinger that he carried them on his person throughout the war. In 1944 he confessed … that he needed them with him for support and inspiration. Pages of The Catcher in the Rye had stormed the beach at Normandy; they had paraded down the streets of Paris, been present at the deaths of countless solders in countless places, and been carried through the death camps of Nazi Germany.”

Considering the horrors Salinger saw as he slogged through hell, writing about the Caulfields whenever there was a lull in combat, from the D-Day landing to the Battle of the Bulge, the nightmare of the Hurtgen Forest, and the liberation of Dachau, it’s possible to imagine that Slawenski’s concept of the “dead Caulfields” is large enough to contain Salinger’s own vision of the fallen, the wartime multitudes of the lost. There’s a heavy but effective touch of poetic license in the biography’s account of what “the carnage of innocents” in the camps did to Salinger’s “fragile ties to normalcy” even as “his pockets burned with pages of The Catcher in the Rye, with their scenes of children ice skating and little girls in soft blue dresses.” Such imagery suggests the children on the lakeside in that timeless view of Central Park on the first page of the Dead Caulfields site. It also suggests the striking figure Salinger himself surely added to The Catcher’s jacket copy, which has Holden “not just strongly attracted to beauty, but almost hopelessly impaled on it.”

Salinger’s Humor

Given the connection the biography makes between the writing of The Catcher in the Rye and Salinger’s traumatic experiences as a soldier, Slawenski’s determinedly solemn interpretation of one of the most humorous works of American literature this side of Mark Twain and Ring Lardner should probably come as no surprise. My only serious quibble with the biography is its relative indifference to Salinger’s unique, indispensable sense of humor. A comparable oversight mars Slawenski’s reading of the author’s last published work, “Hapworth 16, 1924,” which far from being a “low point” in his career (“one of his weakest literary moments”) gives lively, amusing evidence that he’d discovered a fresh approach and a fresh style for “the long-term project” described in the jacket copy for Franny and Zooey, published 50 years ago this fall. What Kenneth Slawenski’s breakthrough biography does abundantly offer, however, is substantial new evidence that the man who died a year ago was perfectly capable of accomplishing the task set forth in the same jacket copy. After stating his awareness of the possibility that he might “bog down, perhaps disappear entirely” in his own “methods, locutions and mannerisms,” Salinger writes, “I love working on these Glass stories. I’ve been waiting for them most of my life, and I think have fairly decent, monomaniacal plans to finish them with due care and all-available skill.”

So maybe it’s not entirely wishful to think that before the year is out the apparition waving from the mountain top may have something more to show us.