|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 29

|

|

Wednesday, July 21, 2010

|

I became an actress only because I had quickly to find some vent for the emotion that inside of me went around and around, never stopping.Luise Rainer

My scream was a product of pure imagination. I had to imagine what was happening to me, and I imagined that the nearest help was far away.Fay Wray

Once upon a time there were two women who became film stars, one born in 1907 in Canada, the other in 1910 in Germany.

Fay Wray, the Canadian, was in more than a hundred generally undistinguished movies, from Gasoline Love in 1923 to Dragstrip Riot in 1958. She was never taken seriously as an actress, never nominated for any awards, least of all from the Academy, but the final tribute paid her was magnificent. When she died in August of 2004, her old friend the Empire State Building dimmed its lights for 15 minutes in her memory.

Since Luise Rainer came to Hollywood in 1935 from Vienna, where her mentor was Max Reinhardt, the publicists called her “the Viennese Teardrop.” She entered filmdom with a bang. winning two consecutive Academy Awards for Best Actress in 1936-1937. Although she was the first star to win two Oscars and the first to win them back to back, her career went nowhere after that. According to cinema lore, she was the original victim of the Curse of the Oscar because “no part was good enough.” In truth, she did herself in by, in effect, telling M-G-M mogul Louis B. Mayer to go to hell. When she celebrated her 100th birthday in London this past January, the two Oscars were prominently displayed in her Belgravia residence.

Fay Wray and Luise Rainer were both back in Hollywood in 1998, honored as stars of the 1930s, along with Gloria Stuart and Shirley Temple Black, at the 70th anniversary Academy Awards, where Billy Crystal introduced Fay Wray as “Beauty who charmed the beast.”

Thanks to Kong

By now you may have guessed why New York’s most famous skyscraper dimmed its lights on August 10, 2004, and posted this message on its website: “We are saddened by the passing of Fay Wray, a wonderful actress and dear friend of the Empire State Building.”

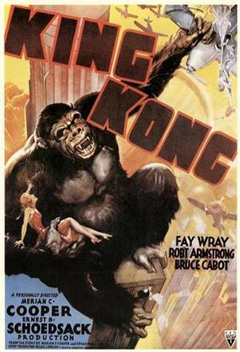

All thanks to the big guy Pauline Kael called “the greatest misfit in screen history.” In the 1994 edition of his Biographical Dictionary of Film David Thomson presented King Kong (1933) as “an untouchable … the epitome of cute sensation that makes great movies” and Fay Wray as “forever the wisp of near-naked woman in the beast’s paw. Sixty years later the image is as stirring and surreal as ever.”

The way Manhattan and Hollywood come together at that pinnacle of Pop, the iconic tower of the American Dream, suggests that if cinema hadn’t existed, New York would have invented it. As the poet John Ashbery observed, the city “is always ready for its close-up” and “never fails to look good on the screen, where it quickens the excitement the way the place itself does.”

When Fay Wray bonded with the Empire State Building, she also bonded with the city. In her 1988 biography, On The Other Hand, she echoes Ashbery: “Each time I arrive in New York, and see the skyline and the exquisite beauty of the Empire State Building, my heart beats a little faster. I like that feeling. I really like it!” At one time she used to resent the way King Kong dwarfed her career, seemingly negating everything else. “But now I don’t fight it any more,” she said in 1963. “I realize that it is a classic, and I’m pleased to be associated with it.”

Spurning Hollywood

At the time of her triumphant, if doomed, Hollywood career, Luise Rainer was more suited to life in New York, where she met and married leftist playwright Clifford Odets (apparently a match made in hell) and was friendly with her double, Anais Nin, at least long and intimately enough to make more than a passing appearance in Volume 3 of Nin’s famous Diaries. I had never seen either of Rainer’s Oscar-winning performances when I looked her up on the International Movie Data Base and found the photograph taken of her in April of this year, still exuding charm and spirit, the embers of a wistful beauty still visible in her expression three months after her 100th birthday. Upon finding that photograph, and realizing that she alone among female stars born in 1910 — including Sylvia Sidney, Paulette Goddard, Joan Bennett, Claire Trevor, Virginia Bruce, and Lillian Roth — had made it to 100, I went looking for two bloated M-G-M blockbusters I’d always avoided, The Great Ziegfield (winner of a Best Picture Oscar) and The Good Earth. I found most if not all of Rainer’s scenes in Ziegfield on YouTube, and immediately recognized the smile and the lively, impish personality still shining through in that photo taken almost 75 years later.

The story behind Rainer’s first Oscar is that it was won on the strength of the famous “telephone scene” and that the limited screen time occupied by Rainer’s performance as Anna Held, Ziegfield’s flighty first wife, was only worthy of a Best Supporting Actress Oscar, if that. The story behind the second Oscar is that Rainer’s subtle, stoic, all but wordless performance as the wife of a Chinese peasant-farmer profited by being the total opposite of her formidably animated Anna Held and the studied acting-with-a-capital-A of her co-star Paul Muni. I haven’t been able to find a tape or DVD of The Good Earth but I trust Graham Greene’s observation that Rainer’s “beautiful performance” not only “carries the movie” but moves him to think of Shakespeare (“in acting like Miss Rainer’s we become aware of the greatest of all echoes”).

Greene begins his review of The Great Ziegfield by calling it “another of those films that belongs to the history of publicity rather than to the history of the cinema.” Comparing it to a “huge, inflated gas-blown object that bobs into critical view as irrelevantly as an airship advertising someone’s toothpaste,” he notes that only Luise Rainer “brings a few moments of real distinction and of human feeling” to “the longest … silliest, vulgarest, dullest novelty of the season.”

What a contrast to that three-hour behemoth is Rainer’s mercurial performance. She’s like a human whirlwind buffeting William Powell’s Flo Ziegfield, drunk with love and joy one moment, collapsing in tears the next. Needy, silly, at times almost ridiculous, and always touchingly, tremulously vulnerable, she gives you the impression that her beauty and renown could vanish at any moment. The ultimate “smiling through tears” moment that supposedly earned her the Oscar — Anna Held’s call to wish her beloved Flo well on his marriage to Billie Burke (Myrna Loy) — isn’t the high point of her performance, only the last gasp. She knows that making the call will be torture, and like everything else in her relationship with Ziegfield, the moment is emotionally volatile; she’s in a frenzy of indecision before her maid dials the number and hands her the phone, and she finally, heartbreakingly, struggles through the call.

Birthmates

Speaking of survivors, how about Gloria Stuart, who celebrated her 100th birthday on July 4. Her role as the 100-year-old who lived to tell the tale in James Cameron’s Titanic (a part turned down by Fay Wray) brought her the sort of attention and acclaim in 1997 that she never knew in her Hollywood life as a contract player. Not only did she receive her first Oscar nomination (for Best Supporting Actress), she enjoyed similar recognition from the Golden Globe awards and tied with Kim Basinger for that category in the Screen Actors Guild ceremony. At 87, she was the oldest actor ever nominated for a competitive, non-honorary Oscar.

Luise Rainier almost outdid her birthmate in the same year, playing a small but central role in The Gambler. Last January she was present at the British Film Institute 100th birthday tribute to her at the National Film Theatre, and in April of this year she returned to Hollywood to present a festival screening of The Good Earth.

While Fay Wray’s last part was on television in 1980 in a Hallmark Hall of Fame presentation, Gideon’s Trumpet, there was, of course, one role and one role only for which she will always be remembered.