|

|

Vol. LXV, No. 22

|

Wednesday, June 1, 2011

|

How good was Stan Musial? Good enough to take your breath away.Dodger broadcaster Vin Scully

A makeshift stage had been set up on the courthouse square in Bloomington, Indiana, a locale immortalized in the opening and closing frames of Peter Yates’s film, Breaking Away. The occasion was a Kennedy for President rally in the fall of 1960 featuring movie stars Angie Dickinson and Jeff Chandler, novelist James A. Michener, historian Arthur Schlesinger, one or two others I can’t remember — and Stan Musial of the St. Louis Cardinals.

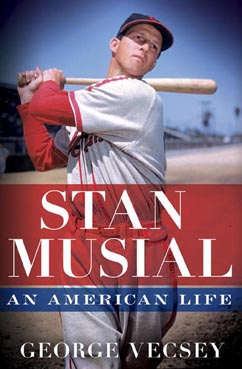

According to George Vecsey’s substantial new biography Stan Musial: An American Life (Ballantine/ESPN $26), Musial had been recruited by Kennedy himself “on a street corner in Milwaukee” while he was waiting for the team bus with the other Cardinals. Having come to the rally more for Musial than for Kennedy, I’d claimed a spot to one side of the stage, looking down on the big jeering, sign-waving crowd. I was upset because here I was close enough to say hi to Stan the Man and people in my hometown were behaving like idiots, waving anti-Kennedy signs like We Don’t Want a Red in the White House.

In Vecsey’s brief reference to the Bloomington rally, Angie Dickinson is quoted to the effect that “it got pretty nasty” with the Kennedy supporters being harrassed “by Republican fraternity and sorority members determined to shout them down.” It was ugly all right. Jeff Chandler huffed and fumed at the mike, as if he were ready to duke it out with the boo brigade, and when it was James Michener’s turn, he told them, “Now I see why they call this a depressed area,” which only brought on more jeers and boos.

Then Musial stood up. Just stood up. He was wearing a suit, or maybe a blazer, but he might as well have been in full uniform with the redbirds on the slanted bat emblazoned across his chest, the Cardinal insignia shining bright. As the truth dawned and the mob realized that they’d been unknowingly jeering one of the greatest baseball players in history, there was a collective intake of breath, a mass “Uhh” and “Ahh.” Apparently no one had told them the Man was in town campaigning for Kennedy.

To be honest, it probably wasn’t that perfect a turnabout, but it remains so in memory: my childhood hero, the player I’d idolized from the age of nine, had deflated that foul balloon without uttering a word. According to Vecsey, something like that had happened on the same tour, which had been expressly organized to target what are now called red states, where Kennedy’s chances were slim. “One day at a windswept airport,” Vecsey writes, Jeff Chandler “heard a roar from the crowd and wondered why Republicans were being so enthusiastic. Then he realized they were cheering for Stan the Man.”

It was on that barnstorming tour, by the way, that Musial and Michener became friends for life. It’s nice to know that my namesake (give or take a “t” or an “e”), a cousin many times removed (he was adopted), traveled, ate, drank, and kibitzed with the Donora Greyhound.

A Perfect, Fearsome Knight

When Musial, who was born in 1920 in Donora, Pa., retired in 1963 after his 22nd season in the majors, all of it with the Cardinals, baseball commissioner Ford Frick called him “baseball’s perfect knight.” Certainly he was perfect when it came to the mathematical distribution of 3,630 lifetime hits, 1815 on the road, 1815 at home. As for knighthood, Vecsey’s book documents numerous instances of chivalrous behavior. While that was part of Musial’s appeal, it’s not what people were in awe of; they may have loved the nice man with the lopsided smile but not as much as they did the stylish, fearsome hitter. If you were a Cardinal fan you loved him for the damage he inflicted on the opposition, notably the hated Brooklyn Dodgers. One of the most storied features of the Musial legend was the way the Brooklyn fans responded to him. With a career batting average of .356 on Brooklyn’s home ground, he was voted into the Dodger’s Hall of Fame, in Vecsey’s words, “in loving tribute to all the dents he put in the scoreboard at Ebbets Field.” It was the Dodger fans who named him Stan the Man, moaning “Here comes the Man again” en masse every time he walked to the plate. Sports writers manufactured and distributed names like the Donora Greyhound. But the Brooklyn fans gave him the one that stuck.

A Lyric Menace

Vecsey devotes a whole chapter to the phenomenon of Musial’s batting stance, “his signature, his trademark,” which he eventually demonstrated “in the Vatican, at the Colosseum, for throngs at the Kentucky Derby and Wimbledon, on the streets of Warsaw or Tokyo or Dublin.” To a 10-year-old just beginning to swing his first Louisville Slugger, Musial’s stance was pure poetry. It was also, though the word wouldn’t have occurred to me at the time, sexy. Other hitters standing at the plate looked like professional athletes waving a weapon. Musial’s stance was so stylishly in-your-face unorthodox, it teased your imagination, fascinated you, drew you in, the way he crouched, coiled and uncoiled. Vecsey quotes baseball statmeister Bill James, who called it, simply, “the Strangest Batting Stance.” The analogy you heard most often came from pitcher Ted Lyons, who compared it to “a little boy peeking around the corner to see if the cops are coming.” But that image, which was to become a cliché in Musial lore, didn’t do justice to it. The way he’d cock the bat, unwind, and cut loose had more of the cobra than the little kid about it. The sequence emanated a lyric menace, at once deadly and beautiful, and the results were spectacular. When he retired, Musial held 17 major league records, 29 National League records, and 9 All-Star Game records, including most times named an All-Star. As of 2011, only three players in baseball history have had more hits.

The Sign of the Redbird

Another lyrical component of Musial’s appeal is on the front of the Cardinal uniform. It was love at first sight when at age 8 or 9, I saw the two cardinals perched on the slanted branch of a baseball bat. The image is still a thing of beauty to me and every time I hear talk of the owners dispensing with it, I start drafting angry letters reminding them that the birds on the bat are sheer genius, one of those supreme emblems of popular poetry Emerson was talking about when he said “the schools of poets and philosophers are not more intoxicated with their symbols than the populace with theirs.”

Then there’s his name. Stan Musial. Any redblooded baseball fan should feel a shiver of pleasure just saying it. It’s one of the passwords of the national pastime, an Open Sesame to those “thrilling days of yesteryear.” Ruth and Gehrig and Mathewson were wonderful names but none sang like Musial in the imagination of a kid in need of a hero. Who else has such music in his name?

Only Human?

I’m prejudiced of course, but I think most people who have seen Stan the Man in action would agree that if he’d played on a New York team, George Vecsey wouldn’t have to begin his book talking about why Musial is, in ESPN’s Tim Kurkjian’s words, “the most underrated great player of all time.” One of the remarkable things about this biography, however, is that rather than giving us detailed accounts of the Man’s prowess as a player, Vecsey seems to be more interested in showing how very human and apple-pie American this legendary figure was. Of course there are references to his demolition of Dodger pitching, the time he seemingly promised and delivered an All-Star-game-ending home run, and the day when he hit five home runs in a double header. At the same time, there are moments in the book that make me think it’s just as well that Musial’s allure wasn’t subject to the total 24/7 media exposure visited on celebrities in the 21st-century. Too much Musial might produce a Polish-American jock doing magic tricks and playing polkas on his harmonica while saying everything is “wunnerful wunnerful” like a nightmare of Lawrence Welk in Cardinal’s clothing.

True to his stated task of writing an American life, Vecsey does give some glimpses of the everyday side of the slugger who terrified Flatbush. But it’s only one side among many. The naïve nice guy superstar was co-owner of a restaurant, a good businessman, and a trusted authority on the best cuts of meat, something Ogden Nash immortalized in a poem (“One moment, slugger of lethal liners/ the next, mine host to humble diners”). At home he was a good Catholic, good husband (married 72 years and counting), good neighbor, sociable, capable of domestic derring-do when he was younger, setting off rockets in a bottle for the kids on July 4 and at Christmastime climbing up on the roof to install figures of Santa Claus and reindeer with lights. He smoked and drank in moderation, told a “bawdy story or two,” and took his responsibilities as a star seriously, signing countless autographs. “You knew you had to share him,” says one of his daughters. “You learned how to share, you had to.”

Baseball’s perfect knight got along with teammates and opponents and even umpires (in 22 years he was never tossed from a game), Politically, he voted for Eisenhower, campaigned for his “buddy” Kennedy, was Lyndon Johnson’s special consultant on physical fitness, met Obama at the 2009 All-Star game, and received from him the Presidential Medal this past February “in the presence of two presidents, poets and cellists, philanthropists and activists.”

St. Looie

There’s much to admire in Stan Musial: An American Life, particularly the background material Vecsey pulls together on St. Louis, the 1904 World’s Fair, and the part the fair and the city play in the work of Thomas Wolfe. Vecsey outdoes himself by unearthing a pungent passage from You Can’t Go Home Again in which a ballplayer friend of the protagonist talks about the rigors of playing in the summer heat of “that ballpark in St. Looie in July.” I’ve never been to St. Looie in July, but I was in that same ballpark, age 11, one memorable late August day to see Stan Musial hit a home run that helped the Cardinals beat the Dodgers 3 to 1. It was my first in-person sighting of the Man in action. I can’t remember the actual home run but I can imagine it because I had the home run feeling again that day on the courthouse square in Bloomington when he stood up and the shouters in the crowd recognized him and went “Uhh” and “Ahh,” too stunned to cheer. Like Vin Scully says, he’d taken their breath away.