|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 22

|

|

Wednesday, June 2, 2010

|

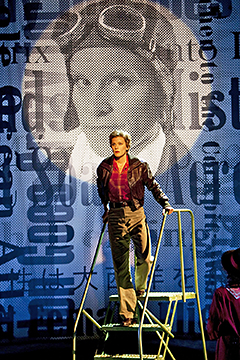

(Photo by T. Charles Erickson)

THREE PLAYS IN ONE: United by the common thread of the history of the early days of aviation, the stories of the Wright Brothers, Charles Lindbergh, and Amelia Earhart are presented as a musical in three separate acts. Shown above is Amelia Earhart (Jenn Collella) in the act that describes Earhart’s role.

|

Experienced any horror stories at Newark Airport lately? Still able to conjure up any of those romanticized anticipations that accompanied airline trips in years gone by, before the terrorism alerts, the endless security lines, the disappearance of all amenities, and the pervasive worries about environmental consequences? The glamour of air travel in the past century has vanished, but Take Flight, an American premiere musical currently at McCarter’s Berlind Theatre, recreates on stage much of the excitement of the early days of flight, and many of the tribulations too.

Take Flight presents the intriguing stories of four American heroes, icons of the early days of aviation: Wilbur and Orville Wright, Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart. But this innovative, richly crafted and creatively staged production is not the feel-good, inspiring show you might expect, in spite of a mostly upbeat score and a number of thrilling moments. The quirky pathologies of the heroes overshadow the patriotism here.

A renowned, veteran creative team — John Weidman (book), David Shire (music) and Richard Maltby, Jr.(lyrics), with direction by Sam Buntrock — delivers the message that obsession, eccentricity, and sheer ornery stubbornness may be more essential to the exploration of new frontiers than genius, creativity, or any other more noble qualities of heart and mind.

These Wright brothers resemble a Laurel-and-Hardy comedy team, or perhaps the two confused vagabonds of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, more than the bold pioneers in the world of flight. This Charles Lindbergh is brash, abrasive, obnoxious, unsociable, and reckless. And this show’s Amelia Earhart is single-minded to the point of fanaticism, as she pursues first her trans-Atlantic solo flight, then her ill-fated round-the-world journey.

Mr. Weidman, who collaborated with Stephen Sondheim in writing the books for Pacific Overtures (1976), Assassins (1990), and Road Show (2008), is, paradoxically, back in the world of Assassins here. Though Assassins portrays a strange collection of American villains — Presidential assassins and would-be assassins from John Wilkes Booth (Lincoln) to John Hinckley (Reagan) — and the protagonists of Take Flight are all acknowledged American heroes, both musicals are fragmented in their presentation; both explore the origins and development of a certain passion, a certain zeal; both explore the nature of an obsession and a pathology that drives individuals to overcome any obstacles in their path. In both musicals there is something American about this sort of ambition, this determination to succeed against all odds, this fixation with reaching a certain goal.

Interestingly enough, Mr. Shire’s score and Mr. Maltby’s lyrics also possesses a Sondheimesque quality of dramatic intensity, richly textured musical accompaniment, ably directed by Kevin Stites, and an excellent pit orchestra (hidden above) of nine, shifting frequently between major and minor keys to enhance the complex characterizations and the subtle changes in tone. The music is often striking and generally appealing as it serves the drama — or in this case the three dramas — and the human interactions taking place, though there are no show-stopping numbers and few memorable melodies.

McCarter Theatre’s production of John Weidman, David Shire, and Richard Maltby’s musical Take Flight” will play through June 6 at McCarter’s Berlind Theatre. Call (609) 258-2787 or visit www.mccarter.org for information.

Mr. Shire has also written a number of award-winning movie and television scores, while Mr. Maltby received wide acclaim for his lyrics for Ain’t Misbehavin (1978), Miss Saigon (1991) and Fosse (1999). Mr. Shire and Mr. Maltby’s prior collaborations include Tony-nominated Big (1996), score by Mr. Weidman, and Baby (1983) on Broadway and Starting Here, Starting Now (1977) and Closer Than Ever (1989) Off Broadway. Mr. Weidman has received more than a dozen Emmy Awards for Outstanding Writing for a Children’s Program for Sesame Street.

Take Flight opened originally in London in 2007 at the award-winning Menier Chocolate Factory, and, during the past two years, has been further developed and shaped under the auspices of the McCarter Lab under the direction of the original creators and the British director Sam Buntrock, director of both the 2007 and the current productions. The extended care, attention to detail and coordination of music, lyrics, and book with production elements are apparent. The quest to bring this production to life — collaborative encounters, multiple problems to surmount and the ultimate exhilaration of creative, technical, and human accomplishment — in many ways reflects the noble struggles of the Wright brothers, Lindbergh and Earhart to keep those large flying machines airborne.

Based on extensively researched historical facts with a large dose of speculative and imaginative material added, Take Flight gives approximately equal time to each of its three stories, and each has its own particular tone, spirit, and appeal. There is some interweaving of the three narratives, two or three musical numbers — most memorably at the opening of the show and in the finales of the first and second acts — and some brief dialogue between characters from different stories, most notably between Lindbergh and Earhart. But each story stands on its own. The themes of failure and success, ambition and artistry, and obsession with flight all overlap, but there is little synergy among the protagonists’ three tales, despite the superb production values, colorfully inventive staging, and seamless flow of action as the plots develop.

The cast is well rehearsed and uniformly, dynamically first- rate. Stanton Nash as Wilbur Wright and Benjamin Schrader as Orville provide a deft deadpan humor that seldom misses the mark. They have traveled from Dayton, Ohio to a Kitty Hawk, North Carolina beach in the very first years of the twentieth century to take advantage of the wind and attempt to solve the mysteries of flight. Failure after failure precedes their ultimate success, as they wonder, “What Are We Doing Here?” Their second act number, “The Funniest Thing,” highlights their comedic gifts, Mr. Maltby’s clever lyrics and the curious circumstances that accompany this wild quest to “take flight.”

Claybourne Elder, displaying powerful vocal talents, is a restless and impatient Lindbergh, refusing to compromise, refusing to take advice and refusing even to take on a co-pilot. It is difficult to like this character, but his relentless determination as he sits in his cockpit, glassed in on three sides above the stage, struggling to stay awake for more than 33 straight hours, cannot help but win admiration, as he is soon to win huge acclaim from the whole world upon landing in Paris after his trans-Atlantic flight from New York.

Jenn Colella’s Amelia Earhart, perhaps the strongest character of all in this production, sums up her life philosophy in “Throw it to the Wind” and decides that flying is “Better than Love,” better than life itself. In several scenes Ms. Colella and Michael Cumpsty, as Earhart’s sponsor-promoter-then husband George Putnam, develop a fascinating relationship based on his adoration of her and her determination to keep flying, first across the Atlantic, then around the whole world. Both are dramatically and vocally outstanding, from their initial encounter to the tragic finale.

The supporting ensemble is spirited, convincing, colorful and versatile in taking on a variety of different roles: reporters, paparazzi, factory workers, rival aviators, bankers and others. William Youmans as chief technician in building Lindbergh’s plane, Bobby Daye as Lindbergh’s first instructor and boss, and Price Waldman as Putnam’s assistant are particularly effective, along with Todd Horman, Marya Grandy, Linda Gabler, and Carey Rebecca Brown.

David Farley’s set design provides a thoroughly functional, richly evocative representation of the worlds of these heroic protagonists, with minimal set and maximum stimulus for the audience’s imagination. The Wright brothers must function on a barren beach, with only a large trunk they have brought with them. Lindbergh sits most memorably in his small cockpit, glassed in on three sides above the stage. A tall stepladder and a second wheeling ladder serve a variety of purposes. Amelia Earhart in the second act flies in a cockpit of her own above the stage, but many of her earlier encounters, most notably with her future husband George Putnam, take place in an office that slides smoothly, seamlessly on and off stage as needed. Ken Billington’s lighting ably assists the scene shifts and also reflects and enhances the tone of this show’s richly varied moments, as the despair of failure and loss interweaves with the elation of flight and success.

Watching and listening to Take Flight cannot measure up to Wilbur Wright’s description of flying as a “sensation of perfect peace mingled with an excitement that strains every nerve to the utmost, if you can conceive of such a combination,” but compared to the traumas of a 2010 trip to the airport and a commercial flight, the pleasures and rewards — intellectual and aesthetic — of this dramatic, musical, human adventure are considerable.