|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 25

|

|

Wednesday, June 18, 2008

|

|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 25

|

|

Wednesday, June 18, 2008

|

|

|

|

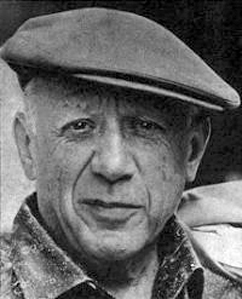

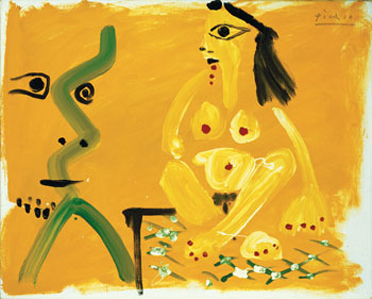

PICASSO IN PRINCETON: Thanks to a donation from 1957 Princeton alumnus Gregory P. Callimanopulos, the University Art Museum has acquired its first painting by Pablo Picasso. “Tête d’homme et nu assis” (Man’s Head and Seated Nude) was painted in 1964 when the the artist had had 83 years to learn how to “paint like a child.” Visitors to “An Educated Eye: Princeton University Art Museum Collections” will be able to see the newly acquired work, as well as special exhibits featuring Frank Stella, Andy Warhol, and Toulouse-Lautrec. This not-to-be-missed chance to see these works and the heart othe collection is free and open to the public through June 15. The exhibialso marks the publication of Handbook to the Collections. Organized according to curatorial department, the new handbook is the first overview of the collection since 1986, and the most comprehensive guide to the museum’s holdings.

| |

“It took me four years to paint like Raphael but a lifetime to paint like child.”

—Picasso

What a roar at the gates of the Princeton University Art Museum last Wednesday afternoon. I was on my way out when the sound exploded, raw, almost primeval in its intensity, like a superamplified dawn chorus from some rain forest in the tropics.

In fact it was a busload of grade-school kids from Hillsborough. Right away I thought of that quote of Picasso’s about learning “to paint like a child” and the one about how “it takes a very long time to become young.”

Surely he’d have been amused by this uproar, the unrefined essence of the free spirit he was still alive to at the age of 83 when he painted the work recently acquired by the museum, the first painting by Picasso to enter the collection.

But imagine being pulled from the school routine for a 30-40 minute ride south (imagine the noise level on the bus) and then walking into the Gothic enclave of Princeton University, like some foreign land, to be escorted into a building fronted by 20 headless, armless monsters (Magdalena Abakanowicz’s Big Figures) that seem to be striding toward you like versions of Klaatu in The Day The Earth Stood Still. Maybe that explains why the kids are making so much noise. Once the group calms down, they’re escorted into a show with the Cyclopean title, “An Educated Eye,” which to a third-grader might suggest something almost as daunting as 20 bronze monsters marching in lock-step.

I wonder what Picasso, with his apparent aversion to the E-word and all it stands for, would make of an “educated eye?” Two big Picasso eyes used to stare out at you from the sculpture, Head of a Woman (constructed by Carl Nesjar under the artist’s supervision), which fronted the museum until it was relocated in 2002. While the title rightly describes the intelligent selection and organization of works of art the University Museum is showing off to celebrate its 125th anniversary, the language seems antithetical to the vision of a creative revolutionary and the point of view of schoolchildren confronted by Frank Stella’s massive Plum Island: Luncheon on the Green. When the docent tells them that Stella painted it the year he graduated from this very university, where he’ll be celebrating his 50th class reunion this spring, they may wonder “What luncheon? Where are the people?” The posted note says the painting before them is “luscious and intoxicating.” But what they see, no matter how closely they look, is a mass of moist, lush color uninhabited by humanity. The lesson is one they may already have learned, that there’s often a gap between what grown-ups say and what you can see with your own eyes.

On these excursions into a heightened reality maybe the kids should be encouraged to come up with their own names for the paintings, or at least the ones that make the strongest impression. Instead of telling them what is or isn’t there, give them the artist’s perogative.

Art and People

Although the grade-schoolers had yet to arrive as I was moving through the civilized hush of the galleries, it was hard not to be distracted by exchanges among nearby adults that can best be described as Woody Allen moments. People talking about paintings, never mind how sincerely or articulately, are frequently doomed to self-parody. At the same time, I was reminded of the scene in Emile Zola’s L’Assomoir where a “primitive wedding party” visits the Louvre. While the bride asks the meaning of one picture, the groom says the Mona Lisa reminds him of his aunt, two of the men snicker and nudge each other at the sight of the female nudes, and someone else stands “open-mouthed and deeply touched” in front of Murillo’s Virgin. Zola creates an amusing and effective contrast between the vast decorum of the museum and the wedding party clumsily moving about “over the shining, resounding floors” with no appreciation of “the marvelous beauties” displayed around them.

When you think of it, though, wasn’t Zola’s intrusion of this ridiculous but very human group into the sublime halls of the Louvre as much a send-up of the academy as it was a picture of the ignorant masses? Parody, self-parody, and art commenting on art are all nicely set in motion by “An Educated Eye,” not only because it establishes an interplay between the works by mixing and juxtaposing creative variations on essential human themes spanning centuries and civilizations, but even more, because parody as commentary is implicit in the accompanying exhibits. Besides enjoying Frank Stella’s big bright in-your-face canvases, the kids from Hillsborough surely had fun with Andy Warhol’s “Do It Yourself,” a simple free-form jeu d’esprit in crayon that plays on both paint-by-the-numbers and “real” art in “Early Warhol in Context.” Then there’s satire on the grand scale in Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s panoramic 1884 oil, “The Sacred Grove,” Parody of a Painting by Puvis de Chavannes Exhibited at the Salon of 1884 and on the adjoining wall, its target, The Sacred Grove, Beloved of the Arts and Muses (1884-1889).

What better teaching tool could educators ask for? All they have to do is point out the various satirical impositions Lautrec has performed. Looking at the group of Parisian men in suits and hats he’s painted into “the sacred grove” (along with a gendarme, a clock, a giant tube of paint, and a loaf of bread), I thought again of the reverse effect of Zola’s intrusion of the Rue Goutte-d’Or crowd into the sacred precincts of the Louvre. Even so, there’s a still stronger whiff of the streets in the Lautrec since the artist can be seen among the men in suits in the act of relieving himself on the sacred grove. You can be sure there will be some back and forth about that on the schoolbus ride home. At the same time, I’d like to think that maybe one of the kids is daydreaming out the window because of a less conspicuous item on display in the same room: the 12-year-old Lautrec’s exercise book with a face sketched in the margin, little more than a glorified doodle but enough to put notions of a creative future in the imagination of an artistically inclined doodler.

Princeton’s Picasso

It was only a little over a month ago that, thanks to a donation from 1957 Princeton alumnus Gregory P. Callimanopulos, the University Art Museum filled a serious gap in its collection by acquiring Picasso’s Tête d’homme et nu assis (Man’s Head and Seated Nude). The 1964 work is displayed a bit off the beaten track at the far end of the main floor, in the alcove to your left (opposite Picasso’s 1935 etching La Minotauromachie). This painting is fun to look at, a joy, pure and simple, and my guess is that the grade-schoolers would have enjoyed it more than almost anything else — if they’d had a chance to see it. I couldn’t help wondering if it had been deliberately set apart to make sure school children were spared the sight of full frontal nudity, even in this form. It seemed absurd somehow, the idea of protecting children from something brimming with the spirit Picasso was talking about when he said it took him a lifetime to learn how to paint like child.

The Princeton University Art Museum is located in the center of the Princeton University campus. Admission is free. Hours are Tuesday–Saturday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.; Sunday 1 to 5 p.m. Closed Mondays and major holidays.

Visitor information (609) 258-3788, or www.princetonartmuseum.org.