|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 25

|

|

Wednesday, June 18, 2008

|

|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 25

|

|

Wednesday, June 18, 2008

|

|

“The fact that about 40 technicians have to wait patiently while a dog condescends to relieve himself on a lamp post gives me great financial responsibilities.”

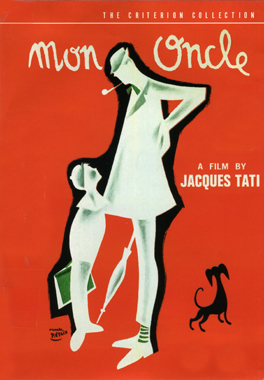

—Jacques Tati on the filming of Mon Oncle (1958)

Speaking of “financial responsibilities,” it took Jacques Tati almost nine years to complete his next film, Playtime, and the only way he could manage that was to borrow from his own funds. A commercial failure, the film left him bankrupt. Playtime is prime Tati but it’s very long and exceedingly subtle, and it doesn’t have any dogs — at least none as lovably rowdy as the ones in Mon Oncle, which marks its 50th anniversary this year.

You can tell a lot about Tati from how he handled the gang of strays happily scampering through Mon Oncle. According to his remarks on the brilliantly designed website, City of Tati [Tativille], the director borrowed dogs from a pound because he didn’t want “circus animals” that had been trained to behave cutely or cleverly. He wanted his dogs to be the epitome of natural movement in a film about the amusingly unnatural way human beings react to whatever environment they inhabit, whether it’s a gadget-riddled household monument to modernity or a plastic factory or a gritty, litter-strewn slice of French life, with market vendors and accordion music and overgrown vacant lots where dogs roam at will, marking their territory as they go. According to Tati, by the time filming had been completed, he, his actors, and the crew had become so attached to those dogs (“and they’d become attached to all of us”) that instead of sending them back to the pound, he put an ad in the paper offering “the stars” of Mon Oncle to people who could give them good homes. Tati’s account of two placements reflects his fondness for the comedy of extremes: “One settled down in the very chic Avenue du Bois. He was a very elegant dog. Another ended up with a little retired man in a suburban house in Asnière.”

Be Careful

For all the awards it won (Oscar, N.Y. Film Critics, Cannes) and its generally acknowledged place among the most notable works of French cinema, Mon Oncle has been faulted for belaboring its gags (“striking the same chord,” as François Truffaut put it) as well as for an oversimplified contrast between the sweet disorder of canine-friendly street life that is the title character’s element (M. Hulot is played, of course, by Tati) and the outlandishly high-tech home giddily supervised by his sister, Mme. Arpel (Adrienne Servanti). The Arpels live in what Tati describes as a “too well-designed universe [univers trop bien agencé],” adding that “one should be free to say to a man who is building a house: ‘Be careful. It might be too well-built’ [trop bien].” Tati claims not to be making a point (“People think it is a message, but it isn’t [c’est absolument faux”). If there’s any “message,” it comes in the form of the advice he would give the officious, humorless M. Arpel (Jean-Pierre Zola) regarding his awkward relationship with his son, Gerard (Alain Bécourt), who prefers the company of his uncle to that of his father: “Your son is only nine and you should enjoy yourself and have a good time with him.”

Tati might also say to his critics, “Be careful not to read too much into my film.” A statement posted on the Tativille site makes clear that he takes full aesthetic responsibility for his work: “I can assure you that on this film I did everything I wanted to do. If you don’t like it, I’m the one to blame.” The extremes of response Mon Oncle has generated reflect the powerfully eccentric complexity of Tati’s creation, particularly as embodied by the Hulot character his creator (and impersonator) termed “an idiosyncratic misfit [personnage inadapté].” Truffaut, for one, complains about the director’s “insane logic” and “totally deformed and obsessive world view”: “The closer he seeks to get to life, the farther away he moves.” Truffaut’s response seems seriously confused (he tempers his criticism in the next paragraph when he says Tati’s “art is so great that we would like to be with him 100 percent”). Mon Oncle, however, is “formed” with a vengeance and much of the charm and wonder of it is in the chemistry of crazy logic that creates some of its most remarkable moments. All Tati needs to do to get “close to life” is to set his dogs and kids loose, put some concertina music on the soundtrack, and wave the wand that animates the tableau vivant of French street life the title character thrives in — even if he often seems to be some form of alien being tricked out in a fedora, a macintosh, a pipe, striped socks, and wielding an umbrella. When M. Hulot strolls about the marketplace fronting the zany, many-leveled Dr. Seuss building he nests on top of, it’s as if the Cat in the Hat walked into a René Clair street scene.

As for Pauline Kael’s incredible assertion that “the unemotional, gawky, butterfingered Tati” is miscast as Hulot, “the warm friendly uncle,” you might as well say that Buster Keaton is miscast as Buster Keaton or Groucho Marx as Groucho Marx. Anyway, what the boy loves in his uncle isn’t that he’s “warm and friendly” (qualities Kael is forcing on the character); it’s that he’s so amusingly and effortlessly the antithesis of the “obsessive world view” embodied by the ultramodern house ruled by the dithery hand of the fastidious Mme. Arpel. The same way Gerard enjoys the harmless human chaos created by the pranks of his schoolmates, he enjoys his uncle’s talent for creating harmless human chaos. The Cat in the Hat needs help from Thing One and Thing Two. Hulot does it without even trying. Ripples of dysfunction follow wherever he goes.

Writing of Tati in 1957, Truffaut’s New Wave colleague Jean Luc Godard declared that “this moon man is a poet” interested in “anything which is at once real, bizarre, and charming” and whose “feeling for comedy” comes from his “feeling for strangeness.” In the real world, Hulot would be a candidate for psychotherapy or antidepressants. He never really smiles and rarely speaks. His movements can look both convulsively spontaneous and as mechanical as those of a wind-up toy. You never see him actually embrace his nephew, let alone the concierge’s daughter, who clearly has a crush on him. Although he allows his nephew to take his hand, Hulot’s preferred way of making contact is to touch the object of his affection with the tip of his finger, something he does with both the boy and the girl, usually after vigorously rubbing his hands together.

What ultimately matters is the way the different textures, sounds, and schemata of Mon Oncle fall into place. The opening sequence puts everything in play. After posting the credits on signs overlooking a construction site with nothing on the soundtrack but the clatter of a jackhammer, the catchy theme music takes over and the dogs race into view on a street so bespattered with garbage you can almost smell it. Among the mutts rummaging in garbage cans is a plaid-clad dachshund, an obvious outsider who wastes no time in making his mark on the crumbling side of a building chalked with graffiti that carries the movie’s title. The scene changes as the dogs race along a more suburban-looking street near the plastic factory (soon to fall victim to Hulot’s genius for chaos) and stop short at the high, buzzer-controlled gate of the Arpel residence. The dog squeezes through the bars (“back home after a romp with the boys,” in effect) and trots up to Mme Arpel who holds him at arm’s length, appalled by the dirt and the mean-streets stench he’s brought into her immaculate sanctuary. Later when Gerard comes home filthy and smelly after his own romp with the boys, he, too, is held at arm’s length and then dragged off to be scrubbed, a process shot entirely in silhouette and one of the most brilliant pieces of pure cinema in a film bursting with them.

The Eyes Have It

The comic centerpiece of Mon Oncle is the party sequence, which I don’t have room to do justice to beyond saying that it’s the work of a master of the human comedy. The customary foibles of guests and hosts, of awkwardness, gallantry, embarrassment, are exploited all the more effectively because the square peg of the occasion takes place in the round hole of a design fabricated without any consideration that human beings might be making use of it. The dimensions are all wrong. It’s not Hulot’s fault that he ends up standing in the pool surrounding the absurd metal fish that spouts water at the touch of a button. Nor is it his fault that the ridiculous Seuss-like devices for holding drinks (long pointed metal poles with little slots for glasses) puncture the water-line feeding the fountain when thrust into the artificial lawn. As wonderful as the party scene is, however, what it leads to is even better.

That night Hulot arrives at the gate with a pair of scissors, never mind why. As he sidles through the gate, he makes a noise that awakens M. and Mme. Arpel; the two round windows on the second floor are alight, and when M. Arpel looks out of one window and Mme. Arpel out of the other, the effect is to make the two windows into a pair of gigantic eyes that look this way and that whenever Hulot makes a sound. It’s magical cinema, a sequence that can stand with great set-pieces in Chaplin or Keaton or Lubitsch. You know what Tati is up to; the concept is obvious, almost inevitable, yet watching it work makes you happy. It’s pure enjoyment. It makes you feel like a nine-year-old kid playing hooky.