|

|

Vol. LXIII, No. 25

|

|

Wednesday, June 24, 2009

|

|

|

Holden Caulfield’s younger sister, Phoebe, shows up in the book by Mr. Colting … having aged into a drug user suffering from dementia.

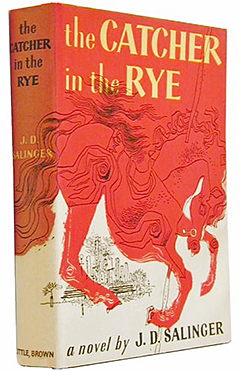

The quote above is from a June 18 New York Times article (“Holden Caulfield Hangs On to His Youth”) reporting that a Manhattan District Court judge has put a 10 day hold on the publication of 60 Years Later: Coming Through the Rye by “J. D. California” (aka Fredrik Colting). The only good thing I can say about a book-length exploitation of The Catcher in the Rye that makes an old man of Holden and a drug addict of his ten-year-old sister is that it inspired me to reread Salinger’s ageless novel with particular attention to the scenes with Phoebe.

Not that Holden isn’t the main issue. He’s been named in Times headlines four days running as if he were a real person. A feature in Sunday’s Week in Review (“Get a Life, Holden”) promotes the idea that kids “just don’t like [him] as much as they used to.” Teachers, students, and experts on children’s literature are quoted in support of the article’s thesis that Holden is no longer relevant. You might as well say the same of Huck Finn, Jay Gatsby, Nick Adams, or Humbert Humbert. Holden and the book he lives in and will never grow old in are beyond topical blather about his alleged lack of appeal for 21st-century youth.

Phoebe

The major beauties of The Catcher in the Rye are all too often ignored in favor of buzz words like alienation. Besides being the book’s wisest and most engaging character, Phoebe Caulfield illuminates the author’s purpose when, in Chapter 22, she backs Holden into a corner with some questions usually left unasked by readers, myself included. The first time I encountered The Catcher (at 17) the sheer fun of connecting with the wildly novel language and the instant appeal of Holden’s attitude precluded any true understanding of just how lost he was. William Faulkner once observed that every time Holden “attempted to enter the human race, there was no human race there.” Holden’s kid sister is way ahead of Faulkner. Phoebe knows he’s given up the attempt. “You don’t like anything that’s happening,” she tells him after he finishes a long diatribe (“I just didn’t like anything that was happening at Pencey”) about the school he’s been expelled from. When he tries to deny it — ”Yes I do. Yes I do. Sure I do. Don’t say that. Why the hell do you say that?” — she keeps at him: “Because you don’t. You don’t like any schools. You don’t like a million things. You don’t.” As he continues stalling, repeating the same denial, she asks him, “Name one thing,” and he can’t, making feeble excuses to the reader: “The trouble was, I couldn’t concentrate too hot. Sometimes it’s hard to concentrate.”

After some more stalling — does she want to know one thing he likes a lot, Holden asks her, or one thing he just likes? — he admits, not to her but to the reader, that all he can think of are two nuns collecting money in “beat-up old straw baskets” and a boy he “hardly even” knew (“a skinny little weak-looking guy”), who was harrassed and bullied by six other students until he jumped out a window and fell to his death. Holden describes running downstairs to find the boy “dead, and his teeth, and blood … all over the place, and nobody would even go near him. He had on this turtleneck sweater I’d lent him. All they did with the guys that were in the room with him was expel them. They didn’t even go to jail.”

While Holden’s reliving this incident, Phoebe’s waiting. He still hasn’t answered her question. “You can’t even think of one thing,” she says, and when he insists, “Yes I can. Yes I can,” she says, “Well, do it, then.”

She’s relentless. Even after he finally thinks to mention liking his dead brother Allie, she won’t let him off: “Allie’s dead — You always say that! If somebody’s dead and everything, and in Heaven.”

He tries to defend himself (“Just because somebody’s dead, you don’t just stop liking them, for God’s sake”), but she’s not done yet. “All right, name something else,” she says. She’s harder on him than a parent or a teacher; no one but the author himself, speaking through his purest, brightest character, could get away with such an inquisition. “Name something you’d like to be. Like a scientist. Or a lawyer or something.” As Holden says in an earlier chapter, “if you tell old Phoebe something, she knows exactly what the hell you’re talking about.” She also shares Salinger’s by now well-known fondness for The 39 Steps (“She knows the whole goddam movie by heart”).

Here it’s as if the author’s holding a mirror up to the book, a mirror held in Phoebe’s hands, which is as it should be since at this point in the narrative he’s come to an impasse that’s at the core of the novel and at least marginally relevant to Salinger’s self-imposed exile from the world of publishing, with its bookchat feuds, shallow, lurid, self-serving biographies, and opportunists like “John David California” who would turn Holden into a 76-year-old and his little sister into a drug addict.

Pressed by Phoebe, Holden admits that lawyers are “all right” (as well he should, with a fresh lawsuit from his creator’s lawyers in the works 58 years later) but that the ones who “go around saving guys’ lives and all,” might not be doing it because they “really wanted to” but because what they “really wanted to do was be a terrific lawyer,” with everybody slapping them on the back. “How would you know you weren’t being as phony? The trouble is, you wouldn’t.”

Thus the impasse. Substitute “writer” for “lawyer” and you know one reason why Salinger hasn’t published since 1965. As soon as he shows his work to the world, he’s exposing his ego, and whether he finds pleasure in good notices and pain in bad or misguided ones, how does he know he isn’t being phony? The trouble is, he wouldn’t, and the only escape is to write for no one but himself.

The Beautiful Answer

Phoebe’s demand that her brother name something he’d like to be leads to the title-invoking image of Holden standing on the edge of a cliff near a “big field of rye” where “thousands of kids” are playing: “What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff … That’s all I’d do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all.”

For a long time, Phoebe has nothing to say to this; she’s absorbing it. Being a catcher in the rye might not make much sense as a profession and it might not clear up the question of his disaffection from humanity, but it satisfies her; her persistence has paid off. She’s provoked him to deliver a beautiful answer, an answer worth writing a book around, a book that transcends all the chatter about generational trends and attitude from sociologists, experts on children’s literature, New York Times feature writers, and well-meaning English teachers like the one who comes into The Catcher after the abovementioned scene with Phoebe.

“Old Mr. Antolini”

My guess is that 60 Years After doesn’t attempt to update Holden’s favorite teacher, Mr. Antolini, an adult version of a “catcher” who isn’t up to the task. That he qualifies for the role is clear when Holden reveals that he “was the one that finally picked up that boy that jumped out the window”: “Old Mr. Antolini felt his pulse and all,” and then took off his coat and put it over the boy and carried him “all the way over to the infirmary.”

When I first read The Catcher in the Rye, I had real problems with the scene where Holden beds down for the night at the apartment of Mr. Antolini and his wife. I still find myself squirming when Holden’s old teacher subjects him to a more elaborate and sophisticated version of Phoebe’s inquisition. Most readers who see the world as Holden does will instantly peg Mr. Antolini as well-intentioned but insufferably patronizing (“I’ll show you the door in short order if you flunked English, you little ace composition writer”) and glib (“One short, faintly stuffy, pedagogical question. Don’t you think there’s a time and place for everything?”). When Holden wakes up to find Mr. Antolini sitting next to the couch in the dark “sort of petting” him on the head, he takes flight, only to torture himself later worrying that maybe he was wrong to assume that Mr. Antolini “was making a flitty pass” at him. The trouble with “old Mr. Antolini” is that a few drinks have him sounding very much like a bad dream of exactly the sort of gushing, self-important book reviewer Salinger probably disdains even more than the ones he imagines lying in wait, ready to savage four decades of work the instant some publisher puts it between covers.

And now along comes someone like “John David California” in time to justify Salinger’s decision to cloister himself and use every means at his disposal to protect his creation. The flap over this latest installment of the Salinger saga also raises some questions about the author, whose 90th birthday was January 1, 2009. He’s said to be deaf in both ears now and recovering from hip surgery in a nursing home.

June is a significant month for Salinger. Besides the June 19 New Yorker containing the last published sighting of his work, “Hapworth 16, 1924,” there was the long quasi commentary on the central figure in the Glass saga, “Seymour: An Introduction,” which The New Yorker published 50 years ago June 6, a date not to be taken lightly by someone who took part in the D-Day invasion. There’s also an appearance by a very Holdenesque character in the story, “Just Before the War With the Eskinos,” in the June 1948 New Yorker.

If the manuscripts locked away in Salinger’s safe are as good or better than “Hapworth 16, 1924,” it would be a crime if, as some fear, the author has asked his heirs to destroy them. Someone with the unlikely name Sierra Philpin has even written a mystery novel around a rescue mission called J.D. The Plot to Steal J.D. Salinger’s Manuscripts. As for the lawsuit inspired by the plot to steal J.D. Salinger’s characters, let’s hope the judge rules for Holden and Phoebe.