|

|

Vol. LXV, No. 11

|

Wednesday, March 16, 2011

|

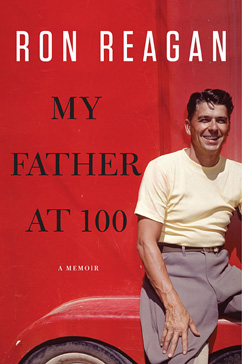

Ron Reagan’s conflicted, witty, diligently analytical memoir, My Father at 100 (Viking $25.95), relives and reshapes a relationship the author is still trying to understand. Just when you think he’s viewing his paternal subject playfully, with his characteristic wit in full flight, you find that he’s either playing rough or scoring points in an ongoing competition. As the 52-year-old liberal son of the brightest star in the conservative universe, Ron Reagan has some serious (and some not so serious) filial issues to work through, and following along with him can be both fascinating and unsettling. The persona he’s projecting is jaunty, even cocky, but there’s no concealing the intensity of his emotional investment in this autobiographical biography, which is why the father-son dynamic he brings to life has such extraordinary immediacy. In effect, he’s still speaking to his father, still debating and competing with the man who died at 93 in 2004 after his movingly announced withdrawal into the no-man’sland of Alzheimer’s ten years earlier.

As My Father at 100 implies, the terminal dementia was only the most extreme manifestation of Ronald Reagan’s tendency to, as his son puts it, “go wandering somewhere in his own head”: “His children, if they were being honest, would agree that he was as strange a fellow as any of us had ever met. Not darkly strange, mind you. In fact, he was so naturally sunny, so utterly without guile, so devoid of cynicism or pettiness as to create for himself a whole new category of strangeness …. I often felt I had to check my natural sarcasm and sense of absurdity at the door for fear of inducing in him a fit of psychological disequilibrium.”

Revealing Photos

Someone with an Oedipal axe to grind could have a field day with My Father at 100. For a start there’s the author’s choice of photography. The vitality and athleticism that he simultaneously celebrates and critiques throughout the book are vividly portrayed in the photographs of his father on both the front and back cover and in the text. Of the father-son images on facing pages in the middle of the book, the one that goes to the flesh and blood of their bond shows little Ron in the family swimming pool clinging to his father’s shoulders and screaming with joyful anticipation as, in the words of the caption, “Father and son prepare to plunge to the bottom of the pool.” They called the game “riding the whale,” and the then-governor’s kid saw it as his special province at a time when his father’s “big-time political career” began attracting “an accretion of staff and advisers.” The new arrivals “never got to ride the whale. Nor did they share our secret football plays, weekend horseback rides, or body-surfing adventures. His sporting, physical realm was territory I staked out for myself.”

The next set of images and captions has distinctly competitive overtones. Directly under a formal family “publicity shot” from 1966 showing gubernatorial candidate Reagan with second wife Nancy and children Ron and Patti is a shot of a sprite-like Ron “hitting the governor of California (my father) with my first-ever snowball.” Note the caption’s primary emphasis on the titled authority figure who is in the foreground ducking, a spray of snow on his back, while his diminutive sunglass-wearing son pelts him from behind with the wicked gusto of a goblin in a body stocking (an amusing foreshadowing of the ballet dancer liberal who will haunt the Reagan presidency). The topmost photo on the facing page shows the tree house Ron and his friends built in the back yard of the Reagans’ Sacramento residence. In t-shirt and slacks, the governor is on his way up the tree, but, as his son takes pains to point out, “wisely abandoned his effort to climb up all the way.” The picture under that one, a true action shot, shows father and son playing football, with Reagan senior in pursuit, reaching not to make a tackle but to do something that calls for a penalty, as Ron makes sure to tell us: “All in fun, but Dad does seem to be trying to strip the ball from my grasp.”

Young Ron has a formidable will and an ego to match, and every time he goes up against his dad, he seems to come out on top. On the injustice done to the Native Americans, he rebuts every argument his father makes in defense of the white settlers (“I could be a terrier on issues like this and I was determined not to let him off the hook”), reducing the governor to lame, exasperated “last words” to the effect that “the Indians just didn’t understand the concept of private property.” As for religion, one day, at age 12, the son simply refuses to go to church. “I don’t believe in all that,” he announces, and nothing the governor can say or do will change his mind.

A more revealing moment comes when the scene is the swimming pool where father and son “raced each other … throughout my childhood years. By the age of six or seven, I was challenging him.” And by the age of 12, he was surprising and humbling his 60-year-old father by winning, a signal event the victor describes with evident relish in play-by-play detail. Up to that point, the father’s “philosophy” about the races or “athletic contests of any kind” had involved “never letting me win” (my italics), figuring that if he “faked” losing, the son would be “smart enough to know.” Although Ron “can’t claim that this swimming race was a life-changing moment,” he presents it as such, with references to “Oedipal watersheds” turning “the keys to adulthood.”

The Report Card

A seemingly trivial point of contention brings the author’s competitive nature rushing to the fore. After revealing his father’s less than stellar grades at Eureka College (Ds in American Literature and the “English Romantic Movement,” “a D in life of Christ”) while declaring that he certainly doesn’t hold his Dad’s “mediocre grades against him” (“nor do I think his C in U.S. history, for instance, had any bearing on his conduct in the Oval Office” — ouch!), he goes on to say, apparently with a straight face (though it’s not always easy to tell when Ron’s narrative “face” is straight), “I simply would have appreciated it if he’d been a bit more understanding — not to mention self-aware — when dealing with my own academic foibles.” Quoting from a fatherly letter gently scolding him for receiving a C- in French 1 and a D in algebra his freshman year in high school, Ron retorts, one on one with his dead father 40 years after the fact, “Tell you what: I’ll trade you my D in algebra for your D in American lit.”

When the letter goes on to express concern about his “inner man,” Ron lets the governor have it: “This was one heaping plateful of foreboding over a couple of lousy grades. Could we not have discussed the matter in more reasonable tones on an upcoming weekend at home? Could he not have admitted, while we were on the subject, that he too had occasionally let his inner man stray from the academic straight and narrow?”

All these years later the letter still rankles, he can’t let it go, and having revived the contentious issue, how to resolve it? What’s the point of stirring up all this ancient angst? Is there a point? What Reagan does, strange as it may seem, is to put the letter in the context of acting: “Dad isn’t really addressing me. He’s writing to a character — the wayward son whose father (played by 1976 West Coast Father of the Year Ronald Reagan) must kindly, but sternly, set him straight.” Then: “I’ve become a useful (if aggravating) symbol, a stock character providing contrast to his own, more Apollonian, example.”

It Could Be a Movie

Thus does Ron turn the great grade debate into a fictional situation featuring two characters, wayward son and kind but stern father; better yet, it could be a movie, thereby evoking a significant part of his father’s life that the author has all but ignored. Out of the book’s 223 pages, Ronald Reagan’s motion picture career is given only one (page 190, to be exact), along with a paragraph about visits to the local moviehouse in Dixon, Illinois, his fondness for westerns, and a reference to the time the pre-school son saw his father get killed in a movie on TV and had to be assured that it wasn’t for real. Google YouTube and there’s the scene in question, from The Killers, which came out in 1964, embarrassingly close to Reagan’s first run for office, since his last role was as a ruthless crime boss who is shot dead, point blank, by Lee Marvin. Or if you want instant access to Reagan as a kind but stern father you can see him in a rare episode from the show he emceed, General Electric Theater, in which his character reads the righteous riot act to a drugged-out whining James Dean.

For almost 20 years Ronald Reagan was making a good living and a name for himself as a solid second tier leading man playing a gamut of roles in various fictional and semifictional situations, most notably and usefully the part of a doomed football hero called the Gipper that has enhanced the image of Reagan in the conservative pantheon. It’s worth noting again that My Father at 100 devotes so little space to the portion of Ronald Reagan’s life most likely to enlighten us about that “strange fellow” with the tendency “to go wandering somewhere in his own head.” Keep in mind that this is an actor who used his most famous line, spoken by the mutilated ladies man in King’s Row, for the title of the autobiography published the year he was entering politics — Where’s The Rest of Me?