|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 13

|

|

Wednesday, March 31, 2010

|

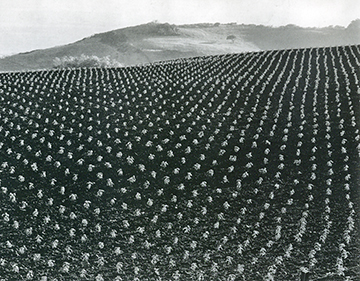

“TOMATO FIELD, BIG SUR” (1937): One of the indescribable “supreme instants” captured by Edward Weston, this gelatin silver print can be seen in “Edward Weston: Life Work “ at the James A. Michener Museum, 138 S. Pine Street, in Doylestown, Pa., through March 28. The exhibit is drawn from the private collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg. Most of the works were acquired from members of the Weston family, including a large collection from his daughter-in-law Dody Weston Thompson, as well as a Weston family album incorporating rare early self-portraits and landscapes. For information about hours and admission fees, call (215) 340-9800 or visit jamam1@michenerartmuseum.org. |

The best way to fully appreciate the 100 photographic works on view in the James A. Michener Museum’s exhibit “Edward Weston: Life Work” would be to rent the gallery for a week, put up a tent, and bed down every night in a world of Westons. If you happen to be familiar with his work, maybe you could find a more practical solution, like multiple visits or going to the nearest library, as I did, to check out Beaumont Newhall’s Supreme Instants: The Photography of Edward Weston (Little Brown 1986).

Among the lesser pieces in the exhibit is Weston’s portrait of the writer D.H. Lawrence made in Mexico City in early November 1924. In fact, the picture is “lesser” only when compared to the much more revealing one reprinted here or measured against the grandeur of stunners like Tomato Field, Big Sur (1937) or the amazing Black Dunes (1936) or the surreal grotto revealed in Artichoke Halved (1930), which was produced the year Lawrence died. Too bad he never saw it, because he might have expressed his response in a poem, a journey into the heart of vegetable darkness, the artichoke inner sanctum.

If anyone could have created word pictures worthy of Weston it was the man he met and photographed in Mexico. According to Covering Photography, a web-based archive, Lawrence was apparently satisfied with the way the pictures turned out, but Weston was “less than pleased,” feeling not only that the sitting had been too brief and superficial but that “the resulting negatives were below par from a technical standpoint.” In the photograph at the Michener, the 39-year-old Lawrence is gazing thoughtfully downward, contemplating something, the hint of a smile on his lips, though his eyes look serious, intent. If you’ve read Birds, Beasts, and Flowers (1923), the book of poems he published the year before the picture was taken, you can imagine him having a silent dialogue with a pomegranate (“Rosy, tender, glittering within the fissure”) or a peach (“Why so velvety, why so voluptuous heavy?”).

Eating the Model

When it comes to finding art in the world of plants, Weston has nothing on Lawrence, who could commune with figs, grapes, and sorb-apples, not to mention fish, bats, and turtles. Somehow it’s harder to imagine him relating to a green pepper like the one Weston immortalized in Green Pepper No. 30, another work done the year Lawrence died. While Weston was no doubt aware that his peppers looked as if they’d been cast in bronze by Rodin, he wanted them to be seen for what they were, the essence, the apotheosis of green pepper. Like Lawrence, he could see humor in the subject. After a barrage of rhetorical questions in “Peach,” Lawrence admits, “I’m thinking, of course, of the peach before I ate it,” then later makes it final, “I’ve eaten it now,” and ends by offering us what’s left: “Here, you can have my peach stone.” As for Weston, the note at the Michener quotes him on the fate of Green Pepper No. 30: “It’s beginning to show the strain and tonight should grace a salad. It has been suggested that I’m a cannibal to eat my models after a masterpiece.”

In Mexico

I have yet to find evidence of how well the writer and the photographer actually knew one another, except for the fact that Lawrence was among the regular guests at Weston’s house in Mexico City. Both men found release and inspiration in that country. For Weston, Mexico was associated with his break from his first marriage, the abandonment of his portrait studio in Glendale, California, and the launching of his affair with Tina Modotti. According to an online article in Counterpunch by Jeffrey St.Clair, “At the center of the [Mexico City] household was Modotti, Weston’s lover and apprentice, his muse and political tutor” while “regular guests at the Weston house” included Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and Lawrence, who was working on his Mexican novel, The Plumed Serpent, at the time. The portraits Weston made of Rivera and Orozco are darker and more atmospheric than the one of Lawrence, who is seen straight, without any apparent embellishment. Perhaps that’s why he looks more vulnerable, more exposed, more like a man who hasn’t long to live.

Born in 1885, Lawrence died of tuberculosis in 1930 in a sanitarium in the south of France (March 2 will be the 80th anniversary of his death). Although Weston, who was born in 1886, didn’t die until 1958, Parkinson’s disease ended his life as an artist ten years earlier.

The Michener show spans Weston’s career, from a 1909 nude to a 1948 landscape. Because his work was something of an unknown quantity to me, the more extravagant manifestations of the precisely focused “Western straight photography” at the heart of his career (1930-1948) left me feeling at once disoriented and fascinated, as if I were seeing images that had been discovered and captured on a distant planet. You may ask what could be more familiar, more earthly, than a celery stalk or a sand dune or a cloudy sky. If you read Weston’s own accounts of his quest, his aesthetic, and his process, the analogy of an interplanetary mission doesn’t seem all that extreme: “To pivot the camera slowly around,” he writes in that landmark year, 1930, “watching the image change on the ground glass is a revelation; one becomes a discoverer, seeing a new world through the lens.”

In a Flash

The ideal of creative flux Lawrence describes at length in his introduction to New Poems (1918) is essentially in accord with Weston’s declaration that success in photography “is dependent on being able to grasp those supreme instants which pass with the ticking of a clock, never to be duplicated … felt as it were — in a flash.” Lawrence would also relate to Weston’s notes written to accompany a 1930 exhibit: “Clouds, torsos, shells, peppers, trees, rocks, smokestacks, are but interdependent, interrelated parts of a whole — which is life. Rhythms from one become symbols of all. The creative force in man feels and records these rhythms, these forms, with the medium most suitable to him.”

Admitted, it’s only a coincidence that the year Lawrence died happened to be a memorably productive and significant one for Weston. Still, I find the association heartening. Say what you will, eighty years ago a master in the medium of images carried brilliantly on in the spirit of a fallen master in the medium of words.