|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 18

|

|

Wednesday, May 2, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 18

|

|

Wednesday, May 2, 2007

|

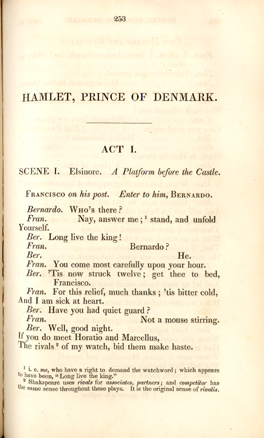

EVERY LETTER A SOLDIER: In 1849, when "Moby Dick" was a gleam in his eye, Herman Melville finally found an edition of Shakespeare "in glorious great type, every letter whereof is a soldier & the top of every "t" like a musket barrel." This page comes from the source he was describing, a seven-volume edition published in Boston by Hilliard, Gray, and Company in 1836. In the same letter, Melville goes on: "If another Messiah ever comes t'will be in Shakespeare's person. — I am mad to think how minute a cause has prevented me hitherto from reading Shakespeare. But until now, any copy that was come-atable to me, happened to be in a vile, small print unendurable to my eyes, which are tender as young sparrows."

|

The bunting-draped makeshift stage on Palmer Square evoked a world of associations: Punch and Judy shows, political rallies, carnival midways and the like, all the way back to the South Bank of the Thames and the original Globe, which was only to be expected since the subject of Sunday’s birthday celebration was Shakespeare. The generally accepted birth date of April 23, 1564, was celebrated a day early with one tribute after another to the scope and power of the Bard’s words and works. As his songs were sung, and his words were read, I was imagining how it would be if he were there, mounting the altar of the stage to read us a sonnet or two or maybe a soliloquy from Hamlet. My fantasy took its cue from the CDs accompanying a coffee table book called Poetry Speaks. I’d been wondering about Shakespeare’s voice ever since listening to recordings of Tennyson, Browning, Whitman, and others right through to Sylvia Plath. How would a Stratford-born Englishman from the 16th century come across to us in 2007? According to some online sources, his Warwickshire accent would have made him sound like an oaf to Londoners of the day, though these same sources not unsurprisingly conclude that once he moved to the city he’d have picked up the diction of Southwark or London. This was the actor, after all, who played the Ghost in Hamlet. In an article on Elizabethan pronunciation, Andrew Gurr offers a half-playful sample of what Antony’s most famous speech from Julius Caesar might have sounded like according to various scholarly estimates:

Frinds, Roomuns, coontrimun, lend me yurr eerrs.

Oy coom too berry Sayzurr, nut too preyze im.

Or, better yet, the opening line of the soliloquy that ends Act II of Hamlet:

Ooh hwut a rroog and pezunt slayv um Eye!

Of course if he’d recorded his voice for an Elizabethan Edison, he might have come off sounding like the actual Edison recordings of Tennyson and Browning where it’s all too easy to imagine you’re hearing a Monty Python routine, John Cleese howling “The Charge of the Light Brigade” into a hail of static. Both poets sound at least 200 years away until Browning wakes up to the spirit of the occasion and stops reading to shout “Hip Hip Hooray!” at the top of his lungs.

An Unknown Country

Another thing that got me started on Shakespeare’s voice was the phrasing of the question I overheard someone asking the other day: “When did Shakespeare first speak to you?” That is, when did his genius first truly move you? When did you finally realize what all the excitement was about? Most bondings with the Bard happen in a theatre, or on the page, or in the classroom. By the time I graduated from college, it had not only never happened to me, it seemed that it never would because of the damage done in the classroom and the theatre, where I was put off by the mannered, precious, overripe way actors mouthed their lines. My senior year in college I’d suffered through a seminar in which we spent the whole term discussing three plays, a comedy, a tragedy, and a history. The professor was a nice man, well past retirement age, but if he’d ever experienced his moment of truth with Shakespeare, he’d long since lost touch with it. At this time, whenever anyone spoke to me of Shakespeare’s greatness (Shakespeare as the world), it was like listening to some starry-eyed traveler celebrating the wonders of a country I’d read about without ever experiencing firsthand.

Burton’s Shakespeare

Then it happened. One night in a Broadway theatre the author took the stage. There he was, Shakespeare in the flesh, all in black, with something of a Welsh accent, and while the words didn’t exactly come “trippingly” off his tongue (they exploded, more often than not), everything worked — language, gesture, movement, thought, all of it coming together most stirringly at the moment when the author of the “play within the play” was telling the actors how to read the lines he’d written.

When I saw Richard Burton in the production of Hamlet directed by John Gielgud, my knowledge of his acting was even more limited than my appreciation of Shakespeare. I’d only seen him in a few forgettable movies. And the play was performed at the height of the Burton/Elizabeth Taylor media frenzy. Proximity to a movie star Cleopatra and all the demeaning publicity attendant on that kind of pop royalty made it hard for me to take him seriously as an actor.

No doubt it helped to be sitting well up front in the orchestra, though I think that what happened would have happened even if I’d been in the balcony. In Richard Burton in Hamlet, a book-length journal of rehearsals based on tapes made by Richard L. Sterne, who had a small part in the production, Burton talks about his favorite speeches. He admits to never particularly liking Hamlet’s advice to the players, with rare exceptions, “largely because I don’t agree with the advice, you know.”

That night had to be one of those exceptions where he enjoyed giving the advice, whether or not he agreed with it.

The Burton Hamlet got me reading through the Works on my own, starting with early comedies such as Two Gentlemen of Verona. Another intense bout of pure reading pleasure came just before graduate school. These orgies of Shakespeare were blissfully irresponsible: no assignments, no reports, no classes.

Close Reading

Reading Shakepeare in graduate school was the summit of the experience that had begun the night Burton brought it all to life. As a close reader writing intricate and ingenious analyses (so you fondly hope), you begin to think you and you alone are in touch with the truth of Shakespeare. You’re ready to mix it up with all the wrongheaded critics and editors abusing that sacred truth, and you write angry letters to the New York Times when they embarrass themselves by giving front-page coverage to the “discovery” of a “poem by Shakespeare” that could never have been written by him, at least according to graduate student protectors of the Word.

Shakespeare came close to luring me into academia. Following the movement of his mind made graduate life an adventure, with expeditions into the dark forests of Macbeth and the stormy moors of Lear and, of course, the ultimate goal, the ascent of Mt. Hamlet, where you follow the map Shakespeare’s given you, sure that only you can figure out the right path until you realize you’re climbing Kilmanjaro, with dead and dying scholars and critics strewn about for miles and none of them anywhere near the top. When I realized that my attempt to get at the heart and soul of that play had become a self-imposed assignment, I bailed out in the foothills.

Now I’m reading Shakespeare again, thanks to an online purchase of the seven-volume edition that unlocked the Word for Herman Melville, a year or two before he embarked on Moby Dick, arguably the most Shakespearean novel ever written.

Hamlet said it best: “There’s nothing good or bad but thinking makes it so.” So we think Shakespeare to life again and again and he’s with us in every season, even if we can’t quite hear his voice.