|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 19

|

|

Wednesday, May 9, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 19

|

|

Wednesday, May 9, 2007

|

|

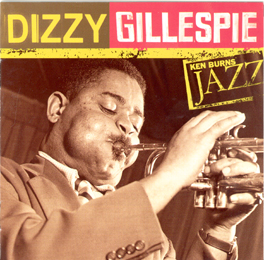

Our late lamented tuxedo cat was named for Dizzy Gillespie, by way of a close friends’ mutt (also late and lamented), who had already been named for him. Both animals grew nicely into the name, though when we were being formal with our cat, we’d pretend his given name was Disraeli. And lovable as he was, Dizzy the dog was not cool. Whenever you got near an open field with him, what composure he had would vanish completely as he became the panting, yelping, bounding essence of dogness. Our Dizzy was like Freddy the Pig’s pal, Jinx. All you had to do was watch him move and you knew why “cat” entered the jazz lexicon.

In case this seems irrelevent to my subject, the fact that a couple of jazz lovers would instinctively choose Dizzy Gillespie’s name for their pets actually does say something about his image. As his fame spread to the culture at large, he became, in effect, a beret-wearing, goateed, wise-cracking pet, an amusing hipster mascot rather than the charismatic embodiment of the new music his partner in bebop Charlie Parker became. The idea of Dizzy as a pet might sound extreme, but it could also help explain why a lot of people, including me, have taken him for granted over the years, or, at worst, have patronized him as a clown blowing with cheeks swollen to cartoon dimensions on a funny-looking trumpet the Cat in the Hat himself might have plucked from his bag of toys. It’s not enough to blame mainstream America’s need for some kind of convenient human persona to stand for and mitigate the weirdness of the bebop phenomenon; more obviously, this misleading caricature evolved from the name itself, which victimized him even as it enhanced his renown. How seriously can you take someone called “Dizzy”? Imagine Dizzy attached to Parker or Coltrane or Miles Davis. It’s true that jazzmen have thrived in spite of a host of silly monikers, from Fat Lady to Satchmo, but Gillespie compounded the problem by exploiting the antic overtones of “dizzy” in his performances; when an interviewer asked him how he’d like to be remembered, he even said, “Just remember how to spell D-I-Z-Z-Y. That’s it.”

In the same interview, with Ben Sidran in Talking Jazz, he clearly enjoyed recalling the “touching” moment President Jimmy Carter shouted “Hey Dizzy!” during a White House visit with some other musicians. In a typically Dizzy gesture, he soon had the president himself sitting in with the group and riffing along to “Salt Peanuts.”

Getting to Know Him

Of course the best way to begin to appreciate what Dizzy Gillespie is truly all about is to listen to his music (the Ken Burns Jazz CD, among numerous others, offers a good selection). No less important, and probably more revealing, is his autobiography, To Be Or Not To Bop, which shows not only that the “clown” was a fighter who came to work with a knife in his pocket, but that he managed his life better than most of his contemporaries. Thanks in great part to a stable marriage, a scholarly commitment to his art, and a resistance to drugs, he survived into old age as a roving ambassador of jazz while “the other half of his heartbeat,” Charlie Parker, drugged and drank and high-lifed himself into an early grave.

It goes without saying that the U.S.A. is in sore need of a few roving jazz ambassadors right now. To Be or Not to Bop offers several nice examples of Dizzy Gillespie, the informal pied piper of American good will. One night in Pakistan he was being transported by bicycle rickshaw to a party far from the hotel he was staying at when he decided he wanted to ride the bicycle himself; so he told the driver to sit down in back and “for maybe a couple of miles” Dizzy pedaled the rickshaw. “And then when we got near the place where the party was I took out my horn and started warming up and a flute player on the roof started accompanying me…. Oh, it was beautiful! This guy was on a roof and I could hear — I’d play, stop, hear the flute, play a little bit more. And we just accompanied one another. That was beautiful.”

It’s funny, and yet dizzily fitting, that this unstoppably joyous musician titled the story of his life by playing on the first line of the melancholy Dane’s most famous soliloquy. When Sidran spoke of the “big part” humor plays in his “musical personality,” Gillespie simply said, “Yeah. Be happy,” and if you want to hear pure, unfettered joy listen to him warble his own flagrantly modified version of “On the Sunny Side of the Street” on his 1957 Verve album Sonny Side Up (his co-stars being Sonny Rollins and Sonny Stitt). After hearing him sing, bebop-Brit style, “Cahn’t you hear the pitter and the patter of the raindrops tricklin’ down your fire ’scape ’n ladder” or “It’s over, Casa-nova,” if you don’t find yourself smiling, you might as well “shuffle off this mortal coil” into “the undiscovered country” with Hamlet.

On more than one occasion at Birdland I saw Dizzy Gillespie move in the space of a minute from slapstick antics (dropping to his knees to impersonate the shrill, diminutive emcee Pee Wee Marquette) to trumpet playing so fast and firey it left you wondering if you even heard what you thought you heard. Listen to the two explosions on his 1947 breakthrough record “Manteca” and you understand what he’s talking about in To Be or Not to Bop when he anatomizes the reading of music: “If you play every note that’s down there, it will become involved and stiff so instead eliminate those notes and make it so the note will be heard without being played” [my italics]. To me this sounds like Hemingway’s “theory of omission” or “the iceberg principle” in Death in the Afternoon that says “If a writer of prose knows enough about what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of the iceberg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water.” In Dizzy Gillespie’s case, the iceberg is more like a flash of fire or summer lightning — you may hear a lot of sounds played incredibly rapidly but the excitement is in what you never quite catch up to. Keats may have had something similar in mind when he wrote that “Heard melodies are sweet but those unheard/are sweeter.”

Among the 16 tracks on the Ken Burns Jazz CD guaranteed to compromise the image of the clownish elder statesman for whom you name your pets is the abovementioned version of “Manteca” by Gillespie’s big band. Writing in Visions of Jazz, Gary Giddins calls it “one of the most important records ever made in the United States” and quotes Gillespie himself comparing its impact to that of a nuclear weapon (“They’d never seen a marriage of American music and Cuban music like that before”). For sheer explosiveness, “Things to Come,” recorded a year earlier, is no less amazing, this time as a big-band translation of the essence of small-group bebop excitement. The sheer joyous ferocity of Gillespian comedy comes together full force with his musical demons in the extended live rendition of “Swing Low, Sweet Cadillac” from 1967 that closes out the CD. This brilliantly raucous number with Gillespie and James Moody creating crazed word-music on the spot would make today’s rappers laugh out loud and might even have seduced some of us back to jazz from rock.

A lot has been written on the question of why Dizzy Gillespie lived a long, productive life while Charlie Parker was burned out at 34. If you read To Be Or Not To Bop, you’ll find that one of the most obvious reasons was his stalwart wife, Lorraine, who had a comic sense all her own, once saying of her husband, “When I met him he was just as raggedy as a bowl of yat ko mein and as poor as a non-bearing beanpole.”

Finally, it all comes down to the power of joy as a life force. If Dizzy Gillespie embodied anything, it was en-joy-ment. According to his wife, the only time she ever saw him sad was “when his mama died and when Charlie Parker died. You’ll never see Dizzy worried or sad. Never. When Charlie Parker died, he didn’t say nothing. He just went on downstairs to the basement, just went down there crying. He never said a word. I knew what he was crying for.”