|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 19

|

|

Wednesday, May 12, 2010

|

|

Willie’s exuberance was his immortality.Roger Kahn

He could do the five things you have to do to be a superstar: hit, hit with power, run, throw, and field. And he had that other ingredient that turns a superstar into a super superstar. He lit up the room when he came in. He was a joy to be around.Leo Durocher

May is Willie Mays’s month. Along with the propitious coincidence of his last name, he was born May 6, 1931, was called up to the major leagues by the New York Giants on May 24, 1951, and would honor the date by wearing the number 24 for the rest of his career. In San Francisco, where the Giants moved in 1958, May 24 is Willie Mays Day. Last Thursday, on his 79th birthday, the California State Senate gave him another day by proclaiming May 6 Willie Mays Day, statewide. When he received an honorary degree from Yale University on May 24, 2004, the purpose of the occasion was not to mark the career or the legend or the life, but to celebrate the 50th anniversary of The Catch, a feat so storied that it has its own wikipedia entry, complete with a diagram of the Polo Grounds, a picture of the well-worn glove Mays used to make the play, and photos and film clips of that iconic moment in the first game of the 1954 World Series between the Giants and the Cleveland Indians.

Doing the Impossible

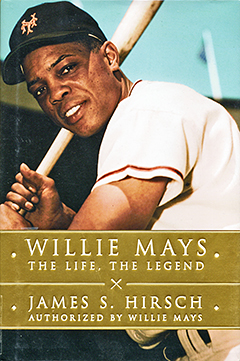

No fewer than ten pages are devoted to The Catch in James S. Hirsch’s Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend (Scribner $30), the first authorized biography of the man many consider to be the best all-around player in baseball history. Hirsch describes two other memorable catches before he even gets to the most famous one. In the first instance, Mays was chasing down a soaring drive that veered suddenly to his right; unable to get his glove on the ball, he reached out and caught it on the run with his bare hand. A few weeks later that same 1951 season, his rookie year, he topped off a great catch with a great throw. Normally, the runner on third would tag up and score easily because the momentum required to spear the ball would handcuff the fielder. Not Willie. Being “in no position to throw,” he “planted his left foot” and “sharply pivoted counterclockwise,” his back to home plate, so that it “appeared as if the impact of the ball had given him the additional thrust to pirouette in spikes. Without hesitating or even looking, he whipped his right arm around and fired the ball,” which “took off as though it had a will of its own, cutting through the air like a bullet,” speeding past the cut-off man to the catcher, runner out, double play, standing ovation from the crowd. Though it never achieved the mythic stature of The Catch, the play became known as The Throw. But as Hirsch points out, “it wasn’t really the throw that made it spectacular. It was Mays’s improvisation, the subtlety of his footwork, the ability to redirect his momentum toward home plate.”

For The Catch, Hirsch provides a montage of eyewitness accounts, Mays “head down, running as hard as he could, straight toward the runway between the two bleacher sections,” the ball hit to the deepest part of the Polo Grounds, “a powerful tracer forty feet above Mays’s head.” Once again, it’s a two-part wonder. First, he’s outrun a line drive hit to the distant reaches of center field, gathering it into his mitt like an apple dropping into a basket, his back to the infield, almost 500 feet from home plate. But the play isn’t over. Two runners had taken off with the crack of the bat, thinking that even should such an impossible catch be made, Mays would be in no position to fire the ball back in time to nail the lead runner, who had tagged up with every intention of scoring from second base. Once again, it’s the throw that compounds the amazement. If you watch replays of the moment, with Mays heaving the ball, seemingly from his solar plexus and in no position to put anything behind it, you may find the account Hirsch quotes a bit unwieldy, Mays whirling and throwing “like some olden statue of a Greek javelin hurler, his head twisted away to the left as his right arm swept out and around,” his hat flying off “in perfect sync with the corkscrew motion.” It was “the throw of a giant, the throw of a howitzer made human.” Although the last analogy comes closest, you could as easily picture Mays as Popeye in a cartoon dilemma, back against the wall, digesting eight cans of spinach and transforming himself into a cannon launching the shot on its way in time to dispatch his arch enemy, the beastly Bluto, or in this case, his fellow pioneer Larry Doby, who never made it past third base.

Citing Popeye is actually less of a stretch than Greek statues and howitzers, especially if, as Hirsch suggests, Mays had a fondness for comic books and cartoons and had been told by one of his teammates that his forearms resembled Popeye’s. The more you read about him, the more Willie Mays seems too good to be true, a fictional creation well beyond Roy Hobbs in The Natural or Shoeless Joe in Damn Yankees. He’s the Marvelous Boy, the Wonder, the Say Hey Kid whose hat falls off every time he accomplishes one of his miracles, a black youth from the south baseball fans of all persuasions fell in love with virtually on first sight.

Mays in Trenton

Willie Mays’s first player-crowd romance in professional baseball outside the Negro leagues was with fans down the road in Trenton, where the Giants had a farm team in the Class B Interstate League. It was thanks to his Trenton fans that he was given his first ever Willie Mays Day in his rookie season with New York, August 17, 1951. The event took place when the Giants were playing the Phillies in Philadelphia’s Shibe Park, with thousands of Trentonians crossing the Delaware along with a nine-man citizens committee to present him with a plaque from the city, $250 in cash, a golf bag and clubs, and an oil painting of himself leaping for a catch.

As you read Hirsch’s account of the magnitude of the adulation Mays attracted, you almost forget that he was also living in Jim Crow America, forced to stay in black hotels or black boarding houses like the one he lived in, alone, in Trenton. Unlike the original barrier-breaker, Jackie Robinson, Mays sustained a “don’t-rock-the-boat” attitude toward his lot. His debut with the Trenton Giants taking place on the road, he found himself “segregated and alone” in a hotel “in the colored section” of Hagerstown, Maryland. It was the first time in his life that he’d been the only black person on an all-white team playing before crowds that were also almost entirely white. Understanding how rocky that night alone might be, three of his teammates climbed a fire escape at the blacks-only hotel and came in to keep him company. Though he told them he could handle it, the three players stayed with him and, Hirsch writes, “slept on the floor. At 6 a.m., they got up, climbed out the window, and returned to their hotel.” In order “to ensure his safety,” his white Trenton teammates had “risked their careers and even their own safety” to show that “racial considerations were secondary. The Team protected its own.” This extraordinary gesture “made a lasting impression,” and undoubtedly helped solidify the nonconfrontational stance that eventually led to Robinson’s disapproval.

Of course Willie Mays on or off the field was never the shrinking violet that his avoidance of the race issue might suggest. It’s not pretty to imagine a politicized Willie Mays. It would have been, as he himself pointed out many times in his defense, unnatural. From all accounts, Mays exuded a flamboyant charm not unlike that of Muhammed Ali. He was no less showy, no less magnetic, no less determined to be the center of attention, but he did it without Ali’s bluster and arrogance, no righteous pose, no by-rote Church of Islam politics, his ego never in-your-face, but irresistibly positive. As his first major league manager Leo Durocher says in the quote at the top, he lit up the room and was a joy to be around.

Leo and Willie

One of the aspects of Hirsch’s book I found particularly revealing was the account of the father-son bond between Mays and the notoriously irascible Durocher, who was arguably the single most important figure in May’s life as a player. Robinson and others who wanted Mays to abandon his neutrality about racism naturally saw a master-slave stereotype in the paternalistic dynamic. The depth of the relationship is strikingly evident in the passage where Durocher breaks the news that he’s no longer going to manage the Giants and “take care” of his protege. Placing “both his hands on Mays’s shoulders,” Durocher said, “I want to tell you something …. You know I love you, so I’m prejudiced. But you’re the best ballplayer I ever saw …. Having you on my team made everything worthwhile. I’m telling you this now, because I won’t be back next season.” Though he’d heard the rumors, May couldn’t believe it. With “tears in his eyes,” he said, “it’s going to be different with you gone. You won’t be here to help me.’” Then Durocher told him “something he would never forget. ‘Willie Mays doesn’t need help from anyone,’ he said, then leaned over and kissed Mays on the cheek.”

In his acknowledgments, Hirsch begins by admitting that “Willie is honest but guarded, and only over time does he open up.” Thankfully, he opened up enough to share scenes like the one above, which he called “his saddest moment in baseball.”