|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 20

|

|

Wednesday, May 16, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 20

|

|

Wednesday, May 16, 2007

|

|

|

When I heard the news of Kurt Vonnegut’s death, the first thing that came to mind was the doomsday message he’d delivered the previous August in a Rolling Stone interview, where he referred to the end of the world as if he were a country doctor breaking the news to a doomed patient: “I’m sorry. It’s over. The game is lost.”

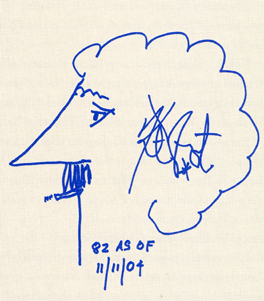

His last book, A Man Without A Country (Seven Stories 2005), delivers the same message, along with his declaration that “Like my distinct betters Einstein and Twain, I now give up on people, too.” Typically, the package containing this last dose of pessimism features a playful caricature of himself on the cover along with the miniature fireworks display of his signature, which is repeated in the hand-lettered statements that head each chapter.

Vonnegut has a signature Dr. Seuss might have given the Cat in the Hat. It’s fun and it’s funny. It jumps off the page at you. You could almost spin it, like a pinwheel; or it could be a piece of antic architecture in one of those daffy Seuss landscapes, a sign on The Street of the Lifted Lorax “at the far end of town where the Grickle-grass grows.” The whole crazy formation is poised on an asterisk, a central, recurring image on planet Vonnegut that could stand for one of his signature phrases, So it goesor Doodley-squat or Hi-Ho, though it actually represents something earthier, according to one of the author’s own drawings in his 1973 novel, Breakfast of Champions. Mainly it’s just there for that scrawled “Kurt Vonnegut” to balance on, like the ball the Cat in the Hat balances on while juggling two books, a fish in a bowl, “a little toy ship,” and “some milk on a dish.”

Kurt and the Cat

It’s time to come clean and confess that this week’s subject was to be the 50th anniversary of the publication of The Cat in the Hat. But then I also wanted to write a column about Kurt Vonnegut, having just started Breakfast of Champions, which I’d never read before. It didn’t take long to realize that Vonnegut’s appeal, his approach, his very style, had something in common with that of Dr. Seuss, alias Ted Geisel. Except for obvious differences, the loose and lively ambiance smacked of Seuss. Here was a children’s book written for grown-ups, complete with drawings by the author. There’s also a certain shaggy Seussness about Vonnegut’s face. Think of the faces of American authors. You have to go all the way back to Mark Twain to find another mustachioed novelist/humorist with a black view of human nature and a twinkle in his eye. Look at the smiling, glasses-down-on-the-nose, here-I-come-ready-or-not author’s photo accompanying A Man Without A Country and it’s possible to discover an elfin charm reminiscent of the jaunty character in the red-and-white-striped stovepipe hat who strutted into a little red house on a rainy day 50 years ago and told two bored children “I know it is wet and the sun is not sunny, but we can have lots of good fun that is funny.”

Put Vonnegut’s funny-sloppy readability together with a countercultural point of view, left-field humor, and shoot-from-the-hip outrageousness, add a dose of science-fiction, and it’s no wonder generations of readers have loved and will go on loving him.

But not as many as have loved and will go on loving Dr. Seuss. Parents, is there anything as exhilarating to read out loud to your kids as The Cat in the Hat or Green Eggs and Ham? Think of it, here’s an artist taking a dare — to make a “first reader” using 225 pre-determined words — and coming up with something wildly unique and immediately, incredibly popular. And he needed only 50 words to concoct Green Eggs and Ham. Here were books that grown-ups and infants and children could enjoy together, laughing at the same sounds and images. Of course there were other, more calming favorites, Good Night Moon, the Sendaks, Corduroy, Paddington, and Babar, among many, but none were quite as captivating, nor as much fun to read. Even the environment in which they were read — parent and child surrounded by a menagerie of companionable stuffed bears and cats and monkeys, their happy-sad faces peeping out of the playtime chaos of the room — seemed to have been created in Dr. Seuss’s workshop. Only he could make such magic out of such a mess, so that as they listened, kids could pretend that the Cat himself had been on the scene, juggling it all and then letting it fall where it fell.

As for Vonnegut, five pages into Breakfast of Champions he describes the book as “a sidewalk strewn with junk, trash which I throw over my shoulders.” Which makes you wonder if he worked as hard at his writing as Ted Geisel apparently did at his. One of my unjust misapprehensions about Vonnegut probably derived from the sense that his books seemed too easy, that he simply tossed them off and went his way, much as he describes throwing the pages of Breakfast of Champions over his shoulder. Critics have denounced him in that regard only to find themselves soundly and eloquently cuffed about the ears in print by novelist John Irving, who studied with Vonnegut and once almost killed him trying to save his life. With Seuss, of course, it’s in the nature of the genre to create simple, visceral connections, to make the words dance on the page: an objective pursued by most novelists in any genre. However, according to Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel, the 1995 biography by Judith and Neil Morgan, The Cat in the Hat was far from easy to write. Laboring inside a 225-word prison (imagine the task for a writer: you not only have a limited vocabulary but none of the words are of your choosing), Geisel got “mad as blazes” and threw the manuscript across the room, comparing the ordeal to “being lost with a witch in a tunnel of love” or to writing “the Baedeker guide Eskimos use when they travel in Siam.”

Kurt Vonnegut himself reveals the part Dr. Seuss played in his life when, in the opening chapter of Fates Worse Than Death (1991), he compares the upcoming “autobiographical commentary” to “one big, preposterous animal not unlike an invention by Dr. Seuss, the great writer and illustrator of children’s books.” He then goes on to suggest that Seuss’s imagery was actually a vivid part of his college life since his fraternity had murals by Ted Geisel in its basement bar, done while the artist (who went to Dartmouth) was visiting Cornell with a “painter pal.” For those readers “who do not know the drawings of Dr. Seuss” (as if such a thing were possible), Vonnegut explains that they “depict animals with improbable numbers of joints, with crazy ears and noses and tails and feet, brightly colored usually, such as persons sometimes report seeing when suffering from delirium tremens.” And don’t forget the Cat’s grinning agents of chaos, Thing One and Thing Two, with their blue Afros and red pajamas, not to mention their mad brother, Green Eggs and Ham’s Sam-I-Am whose incessant nattering seems somehow relevant to politics in the land of Red and Blue, Bush-I-Am’s America.

The Mess Thing

Like Seuss’s creature, the Lorax, who sports a Vonnegut-style mustache, the author of Breakfast of Champions has long been warning of the evils man has inflicted on the planet. His gloomiest assessment of the present reality (as quoted in the Rolling Stone interview) suggests an endgame well beyond the devastation the Lorax tried to prevent: “I’m talking about us killing the planet as a life-support system with gasoline. What’s going to happen is, very soon, we’re going to run out of petroleum, and everything depends on petroleum. And there go the school buses. There go the fire engines. The food trucks will come to a halt …. We’re crazy, going crazy, about petroleum. It’s a drug like crack cocaine.”

Remember “the Vision Thing” George W. Bush’s father used to cite during his term in office? As his son’s administration teeters on the edge of chaos like a ramshackle castle out of the hallucinatory imagination of Dr. Seuss, the dimensions of the mess have achieved an almost visionary splendor. It makes you wish Seuss could draw it with Vonnegut writing the caption.

The last word, however, belongs to that adorably determined pessimist, that joyless party-pooper fusspot, the Fish in the Bowl who comes flopping and gesturing out of his habitat (who else but Seuss could suggest hands in motion without drawing them?) to warn against impending disaster when the Cat in the Hat comes strutting into the little red house. Looking at the carnage, the Fish’s summation of the state of affairs isn’t all that far from Kurt Vonnegut’s: “This mess is so big and so deep and so tall, we can not pick it up! There is no way at all!”