|

Although they were tired and in anguish, they listened to what the baker had to say. They nodded when the baker began to speak of loneliness, and of the sense of doubt and limitation that had come to him in his middle years.

—from Raymond Carver’s “A Small, Good Thing”

My favorite Raymond Carver moment comes when the baker in “A Small, Good Thing” feeds fresh-baked rolls to the bereaved couple he’d been plaguing with crank phone calls. If you look for this pivotal sequence from Carver’s work in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, the collection he intended it to appear in, you won’t find it because the author’s editor at Knopf, Gordon Lish, dispensed with it when he “minimalized” the story and retitled it, “The Bath.”

The Lish-Carver relationship is the subject of an unsigned article in the December 24 and 31 2007 New Yorker (“Rough Crossings: The Cutting of Raymond Carver”). If you care about Carver, who was born 70 years ago this past Monday and died 20 years ago this August, you may find the letters that accompany the article at once fascinating and painful to read. All but one of them are from the author, and they leave no doubt that Lish’s contribution was enormous; he was “an inspiration,” the “ideal reader,” the “mainstay” who was advised “not to worry about taking a pencil to the stories if you can make them better, and if anyone can you can.” Mere months later comes the long, incredible, agonizing letter of July 8, 1980 that begins “I’ve got to pull out of this one,” written after Carver had his first look at the extensive cuts and changes Lish had made on a manuscript that was about to go into production. It seems possible that the earlier letter’s heady enthusiasm (“So open the throttle”) may have encouraged Lish to take the outlandish liberties he did. Whatever happened, the July 8 letter can tear your heart out, especially if you’re a writer. Here’s a man coming into his own as one of the most significant literary forces of his time reduced to near-abject pleading that work he rightly felt represented an important movement in the development of his art be spared the editorial axe.

According to the New Yorker, which paired the letters with the original version of one of the most heavily edited stories, Lish’s cuts consumed more than 40 percent of What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. While most authors would consider such a sweeping, peremptory act little better than righteous vandalism, Carver was intimidated by the magnitude of his debt to Lish (“I’ll say it again, if I have any standing or credibility in the world, I owe it to you”). Lish had not only introduced him to the world in the pages of Esquire and piloted his first book, Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?, through the devious currents of the publishing world, he’d been his mentor, showing him the way and helping shape his voice, his identity as a writer.

It’s all too easy to cast Lish as the villain of the piece, but according to the evidence provided by the New Yorker — the full text of Carver’s original story, then titled “Beginners” and the online text showing Lish’s actual handiwork — the idea of “villainy” is debatable. After reading the online text and taking into account the fact that Carver chose to keep the story as Lish had reworked it even after he’d had the opportunity to run the original version in a later collection, it’s hard to deny that what survived this act of major editorial surgery is a more striking piece of work. Right away, by giving “Beginners” (and the collection itself) the clearly more Carveresque title, ”What We Talk About When We Talk About Love,” Lish shows his understanding of Carver’s authorial character and language and the appeal they’d had and would continue to have when the book was taken up by reviewers, critics, and readers. You have to believe he knew what he was doing, at least in this instance, when he removed most of the protracted anecdote about stereotypical senior devotion at the center of the story, which is about two couples (Herb/Mel and Terri, Laura and Nick) drinking and (what else) talking about love. While no one but Lish is likely to understand the rationale for changing the Herb character’s name to “Mel,” the relentlessly edited online version offers about as lucid and instructive a picture of prose sculpture in action as you’ll ever see.

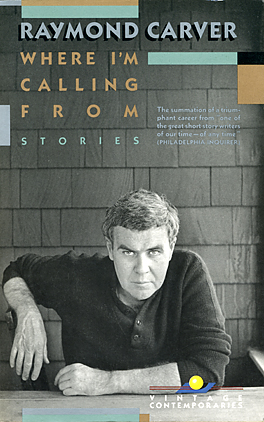

As I already suggested, if Carver had problems with the truncated story, he could have included the original version two years later in Cathedral. Because the heavily edited version, complete with Lish’s ending, is the one he reprinted in his 1988 collection, Where I’m Calling From, it seems clear that he’d come to accept the fact that, in this instance, the editor knew best.

But that still doesn’t let Gordon Lish off the hook.

An Abomination

I’m surely not the only reader who first “saw the light” — Carver’s light — when reading “A Small, Good Thing” in Cathedral. Before that, though I could tell that he was a special writer, I’d never really connected with his work. One of the most wrenching admissions in that distraught July 8, 1980 letter to Lish is Carver’s concern that friends and fellow writers who had seen some of the stories in their original form would be shocked by what he’d allowed Lish to do to them. In view of what Lish did to “A Small, Good Thing,” what’s truly shocking is that any amount of past gratitude and love and friendship could have prevented Carver from denouncing the perpetrator of the abomination and then making a trip to New York to personally rescue his book. Yet he backed off and when What We Talk About When We Talk About Love came out, the story that should have been there, one of Carver’s glories, was missing and in its place was the abovementioned travesty, “The Bath.” If you ever want to witness a graphic example of the evils of minimalism, read “The Bath” before or after “A Small, Good Thing.” The story is so denuded of life that it seems to have been written by a robot.

The violation was presumably a key factor in Carver’s eventual break with Lish. When Thomas Wolfe broke with his editor, it was because he felt he had to prove to the world that he didn’t need Maxwell Perkins. “A Small Good Thing” was proof enough in itself that Carver had evolved into a greater writer than the one his friend and editor had helped bring to light. The crowning and somehow Carveresque irony of it all is that in spite of the pernicious presence of “The Bath,” and numerous other editorial liberties, What We Talk About When We Talk About Love proved to be Carver’s breakthrough collection, and the nature of the response (with references to the stories’ eloquent “silences”) left no doubt that Lish’s editing had been indispensable to its critical success. In “A Small, Good Thing,” the recipe — a mortally wounded child, a birthday cake, a surly baker making crank phone calls, the anger his parents lavish on their unknowing antagonist, and the baker’s lovely penance — is mixed, put in the oven, and done to so nice a turn that it has you sitting with the parents in the warm, fragrant bakery of Carver’s art.

By the end, readers know who the baker really is anyway. “He had a necessary trade. He was a baker. He was glad he wasn’t a florist. It was better to be feeding people.” So the grieving couple smell the fresh bread, and then taste it, and they listen to the baker. “They talked on into the early morning, the high, pale cast of light in the windows, and they did not think of leaving.”

We don’t want to leave the bakery either. And since this is a significant anniversary year for Raymond Carver, perhaps we can look forward to some celebratory reissues of his work.