|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 44

|

|

Wednesday, November 3, 2010

|

This guitar which laughs and weeps, guitar with a human voice.Jean Cocteau

This gypsy is worth a Goya!Vicomtesse de Noailles

Newlywed, settled in a cottage overgrown with jasmine and myrtle, Samuel Taylor Coleridge composed “The Eolian Harp” during one of the rare happy moments in his doomed marriage. The words he found for what happens when the “desultory breeze” caresses a lute (“Such a soft floating witchery of sound”) engendered thoughts of “the one Life within us and abroad,/Which meets all motion and becomes its soul,/A light in sound, a sound-like power in light,/Rhythm in all thought, and joyance every where.”

Something very like Coleridge’s “soft floating witchery of sound” returns 135 years later in the form of music being heard by an artist living above a cafe near the harbor in Toulon in July 1931. The enchantment wafting forth from a mere guitar sends the artist, one Émilie Savitry, running down the stairs in his slippers and dressing gown to find the source, too late; the musicians have vanished. The waiter tells Savitry that they are gypsies who stop by to play for coins from time to time and that the one who made such compelling music has a crippled hand. After finally tracking down the guitarist, asking him to play, and being bewitched yet again, Savitry invites Django Reinhardt upstairs to listen to records. Incredible as it seems, given the rich jazz flavor of his sound, the gypsy has never heard Duke Ellington or Louis Armstrong. According to Michael Dregni’s lively biography Django: The Life and Music of a Gypsy Legend (Oxford 2004), when Savitry plays Armstrong’s “Indian Cradle Song,” Django is “overwhelmed,” “mute and dazed in the blaze of the sun …. Right away he understood Armstrong.” Listening to the sound of a trumpet “like archangel Gabriel’s divine horn,” Django “put his head in his hands, unashamedly starting to cry. ‘Ach moune! Ach moune!’ he repeated over and over again — a Romany expression of stupefaction and admiration” meaning “My brother! My brother!”

Joyously Unhappy

The music goes round and round and ten years later, give or take a few, someone introduces the sound that “meets all motion and becomes its soul” to an American soldier named James Jones, who is so moved by it that he puts Django in his celebrated, best-selling novel, From Here to Eternity, and takes up residence in Paris. His plan is to base his next book (a project he never completed) on the life and music of the man who grew up in a gypsy encampment outside the City of Light and became the most celebrated jazz guitarist of his time after overcoming the effects of the fire that deprived him of the use of the third and fourth fingers of his left hand.

Some 460 pages into Eternity, Andy, a guitar-playing soldier, is raving about Django to a group that includes Prewitt, the bugler-boxer hero so memorably played by Montgomery Clift in the 1953 film. After Andy insists that the “poignant fleeting exquisitely delicate melody” of Django’s guitar cannot be described, Jones makes a noble, characteristically uneven effort to do just that:

“You had to hear … the steady swinging never wavering beat with the two- or three-chord minor riffs at the ends of phrases, each containing the whole feel and pattern of the joyously unhappy tragedy of this earth (and of that other earth). And always over it the one picked single string of the melody following infallibly the beat, weaving in and out around it with the hard-driven swiftly-run arpeggios, always moving, never hesitating, never getting lost and having to pause to get back on, shifting suddenly from the set light-accent of the melancholy jazz beat to the sharp erratic-explosive gypsy rhythm that cried over life while laughing at it.”

Django Meets Samantha

Enter, would you believe, Woody Allen, whose Django homage, Sweet and Lowdown (1999), actually comes close to capturing the feel of the “joyously unhappy tragedy” Jones is trying to express. At the end when Sean Penn’s Django-obsessed guitarist realizes he’s lost the love of his life, he sobs (“I made a mistake!”), smashes his guitar, and crumples to his knees. The scene is reminiscent of the conclusion of Fellini’s La Strada, where Anthony Quinn’s Zampano crawls toward the sea, sobbing with grief after hearing music he associates with Gelsomina, the elfin waif he abused and abandoned. Sean Penn plays Emmet Ray, the self-proclaimed “second greatest guitarist in the world,” with a brilliant combination of bravado and body language, but he’s eclipsed by Samantha Morton’s mute Hattie, who is, like Giulietta Masina’s Gelsomina, unforgettable. A silent movie unto herself, Morton gives the film its charm and pathos, and even its music. When Hattie hears her boorish, pathetically egomaniacal lover play for the first time, you can see the music stirring, enrapturing, filling her up, becoming her. It’s in her heart, she’s breathing it, living it, and it’s the music of Hattie’s mute, radiant, happy-sad presence, not Howard Alden’s Djangoesque playing on the soundtrack, that stays with you and haunts you long after the movie’s over.

Illiterate

According to Dregni’s biography, the gypsy “was drawn to the cinema like an innocent to the inferno.” He loved Chaplin, the French serial Fantomas, and he picked up points of style from pirates and musketeers, “learned how to walk with a gangster’s swagger,” and “how to tilt his fedora over one eye just so.” Deeply embarrassed by his illiteracy (his partner in the Quintette du Hot Club de France, Stéphane Grappelli, taught him how to sign his name), Django avoided the Metro because he couldn’t read the station signs and could only pretend to read menus and contracts. His shyness about his imperfect French was such that he rarely spoke in public; one band-mate likened him to Harpo Marx (when Woody Allen was coaching Samantha Morton in her silent role, he told her to think of Harpo). With his guitar (like Harpo with his harp), “he was a different person. His guitar joked and jested, laughed and cried …. With his guitar in his hands, he was pure poetry.” Like Morton’s Hattie, in her eloquent silence.

In fact, Django was anything but shy when it came to playing billiards, buying expensive cars and driving them to death, gambling as if there were no tomorrow, and composing grandiose works no one could perform. He labored over a symphony in the early forties, with Jean Cocteau promising to write a libretto for a choir of “between 80 and 300 singers depending on Django’s fantasy of the moment.” In a 1954 Melody Maker interview, Grappelli said that Django “liked great things” and “experienced them in a way they should be experienced. To see his expression in the glorious church of St. Eustache, hearing for the first time the Berlioz Requiem, was to see a person in ecstasy.”

Django in Xanadu

It’s interesting that Django’s orchestral ambitions coincided with the German occupation of Paris. While other Romanis were at risk of deportation and death, he was thriving, apparently enjoying a degree of protection because he had fans in the German high command, including Luftwaffe officer Dietrich Schulz-Köhn, nicknamed “Doktor Jazz.” There were limits, however, when it came to staging works like his gypsy Mass or the symphony he called Manoir de mes reves. The story of that work resembles the narrative Coleridge appended to “Kubla Khan,” written a few years after “The Eolian Harp.” According to Michael Dregni, “The image and musical theme came to him in a reverie” wherein “he dreamed he was in a grand chateau lost in the midst of a never-ending forest; it was midnight and he was playing on a large pipe organ the music that became Manoir de mes reves.” The end result, a massive score compiled by an assistant who transcribed his ideas, was declared “unplayable” just days before the scheduled concert. Apparently the conductor, who was already “overwhelmed by the modernistic music and its daring harmonies,” feared that “the Propagandastaffel would react against such modernity.” The “soft witchery” of the haunting tone poem that Django distilled from his symphony can be heard on YouTube and in a bizarre 21st century incarnation as the music for the Mafia video game, The City of Lost Heaven, a production of Illusion Softworks.

Finding Django

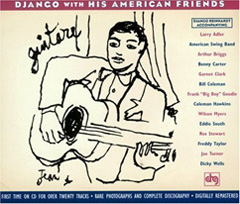

As for records, I’ve been listening to several collections, mainly Django With His American Friends, a 3-CD set with a cover featuring Jean Cocteau’s sketch of a young-looking, somewhat romanticized Django. The only problem with this invaluable set, which includes sessions with Coleman Hawkins, Benny Carter, Bill Coleman, Dicky Wells, and Eddie South, is that there’s not enough Django. I found the quickest, widest-ranging, most illuminating source is, as always, on YouTube, from the relatively common Hot Club sides with Grappelli to Django’s delicate early work with Jean Sablon (notably “La Derniere Bergere” and “Darling Je Vous Aime Beaucoup”) and orchestral pieces like “Nymphéas,” from 1942, which you would swear had been composed and arranged for Duke Ellington by Billy Strayhorn.