|

|

Vol. LXIII, No. 44

|

|

Wednesday, November 4, 2009

|

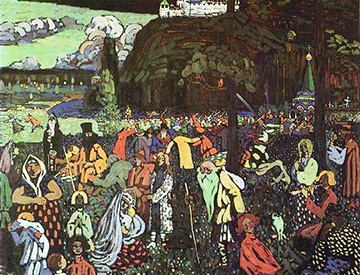

“COLORFUL LIFE”: Painted in 1907, this tempera on canvas by Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) is the first work on display in the Guggenheim’s 50th Anniversary Retrospective. While it may appear to be atypical in its representational “normalcy,” it’s actually closer to the Russian heart of his career than his later, more geometrical creations. A lovely, smaller work in the same style, “The Procession,” is on display at the Princeton University Art Museum. The 50th anniversary of the 1959 opening will be celebrated with a Free Day on October 21, from 10 a.m. to 5:45 p.m. For information about times, admission, and related events, phone: (212) 423-3500; the box office number is (212) 423 3587, or email: boxoffice@guggenheim.org. |

Technically, every work of art comes into being in the same way as the cosmos — by means of catastrophes, which ultimately create out of the cacophony of the various instruments that symphony we call the music of the spheres. The creation of the work of art is the creation of the world.Wassily Kandinsky

At the Library Hotel on Library Way — otherwise known as 41st Street off Madison — you can live in your subject area. The 3rd floor is Social Science, the 4th Language, the 5th Math and Science, and the 6th Technology. My preference would be for a room on one of the upper floors, like the 7th (the Arts), the 8th (Literature), the 9th (History and Geography), the 10th (General Knowledge), and the 12th (Religion). Of course there is no 13th floor. Not having specified a category, my wife and I ended up on the 11th floor (Philosophy) in the Paranormal Room (11.05), where the shelves by the bed are filled with volumes on the occult, ghosts, ESP, etc., with a copy of Carlos Castaneda’s The Art of Dreaming on the bedside table. The folks at the front desk gave us a chance to switch (“some people say it’s haunted”), but we took their word for it that the ghosts were friendly, and anyway, we’d been “upgraded” to the Paranormal from a lesser room, plus a bottle of Prosecco had been thoughtfully provided with a card (we were celebrating an anniversary), so who’s to complain?

“Paranormal” is generally defined as an experience or phenomena that can’t be explained or understood in terms of “current scientific knowledge.” The operative word, “para,” means “beyond.” Since most of the best things in life are beyond normal, a truly deluxe, fully stocked Paranormal Room would provide, speaking for myself, copies of the works of Shakespeare, some prints by William Blake, a CD set of Berlioz’s Damnation of Faust, a copy of Moby Dick, and a tape that included Van Morrison singing “Mystic Eyes” and Thelonious Monk playing “Misterioso.” That’s just for starters. In fact, the volume most appropriate to the true essence of such a room would probably be Dover’s edition of the Complete Books of Charles Fort, who spent many hours a block away at the main branch of the great library for which the hotel is named uprooting the archives for examples of phenomena “stranger than anything in your philosophy, Horatio.”

Skywalking

To someone growing up in the midwest in the 1950s or 1960s, one of the most characteristic features of New York City was the erratic, eccentric, and sometimes downright lunatic behavior you could depend on seeing almost any time you went out the door. This usually was manifested by people walking down the street talking to themselves, something many presumably normal individuals can be seen doing in 2009, thanks to cell phones and headsets. Another characteristic feature was the city’s genius for exceeding your expectations. The buildings were always taller, the crowds thicker, the traffic heavier, the possibilities more complex, compelling, and intimidating.

At the same time, there’s a New-York-ness that somehow ties it all together. Not to belabor the beyond-normal idea, but what we felt strolling around the city last weekend was the sense that a superior being was working behind the scenes to make the place even more engaging than it already was. For instance, the coming together of enlightened planning and big bucks ($50 million, it’s said) to turn the derelict, overgrown section of elevated railway on the West Side into a greenway called the High Line that makes it possible to skywalk for six or seven blocks south of 20th Street through a brave new world of civilized wildness, of pebble-dash concrete walkways and clump-forming grasses, sumac and smokebush, and dizzying clusters of asters and cone-flowers.

Wondrous and Delirious

For artists and architects like Rem Koolhaas the line from the song “Manhattan” (“the wondrous city’s a great big toy”) says it all. Just look at the image Koolhaas used for the cover of his 1978 book Delirious New York, which, according to the jacket copy on the Monacelli reprint, establishes the city “as the product of an unformulated movement, Manhattanism, whose true program was so outrageous that in order for it to be realized it could never be openly declared.” Madelon Vriesendorp’s surreal jeu d’esprit Flagrant délit shows the Empire State and the Chrysler Buildings slumped on the same bed like a couple of drunken, post-coital revellers after a night on the town, caught in the searchlight from the RCA Building glaring down at the guilty couple from the doorway. What better picture to frame and hang above the bed in the Library Hotel’s Paranormal Room?

Celebrating the Guggenheim

Sexy, anthropomorphic skyscrapers also make a segue of sorts to Frank Lloyd Wright’s “great big toy,” the Guggenheim Museum, which opened to the public at 2 p.m. on October 21, 1959, some six months after its architect’s April 9 death. The 50th anniversary of the opening will be celebrated with a Free Day from 10 a.m. to 5:45 p.m. featuring everything from a raffle, tours, and photo ops to free Guggenheim cookies. Now considered Wright’s swan-song masterpiece, the building’s design was attacked by artists and critics alike in the late 1950s, with a New York Times editorial claiming that “the net effect … will be precisely that of an oversized and indigestible hot cross bun.” Wright’s response was at once playful and severe. When the model was unveiled, he patted it “as if it were a baby,” pointing out that it was “built like a spring,” so that when “the first atom bomb lands on New York, it will not be destroyed. It may be blown a few miles up into the air, but when it comes down it will bounce!” [emphasis Wright’s]. As for those artists claiming that the design would distract from, rather than display, their art, Wright said, “I am sufficiently familiar with the incubus of habit that besets your minds to understand that you all know too little of the nature of the mother art — architecture.”

Wassily Kandinsky might have shared the concerns of those artists, a group that included Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, and Willem de Kooning, but the 50th anniversary retrospective of his work lining the architect’s bright, breath-of-fresh-air ramps is a stunning and definitive celebration of the building’s beauty and suitability as a showplace for art and the human spectacle of the people viewing it.

Magnetism

When Wright first visited the site where his masterpiece was to be built, he realized that it had possibilities beyond even his most ambitious imaginings, calling it “a magnet that would draw many people” with “a desire to see that wonder.” With this explosion of Kandinsky housed inside it, Wright’s magnet is drawing multitudes; the paintings show off the building and the building more than returns the favor by affording new views and angles for work that, interestingly enough, becomes less compelling (and by definition less “paranormal”) only when the artist attempts to apply the geometric forms associated with science and “the mother art” too literally. Writing in The New Yorker, Peter Schjeldahl suggests getting the later “compulsively tidy” compositions out of the way by starting at the top of the winding ramp and viewing the show in reverse. Wright himself suggested taking the elevator to the top in order to “eliminate the to and fro, the back and forth,” so that instead or “retracing your circuit,” you end up on the ground floor where you began.

Even if you’re not coming to this exhibition from a night on the Philosophy Floor of the Library Hotel, seeing it as an ascent rather than a descent makes more sense when the works at the top are the least interesting and your eyes are already brimming with visions “as thrilling as an Easter sunrise,” in Schjeldahl’s words. But when you think of it paranormally, a phrase like “Easter sunrise” seems too earthbound to do justice to Kandinsky’s most inspired work. Scientists can explain a sunrise, no problem, and Easter can certainly “be understood” in terms of theology and a seasonal holiday, but these visions, the wildest and the best of them, transcend weather, religion, and “scientific knowledge.” In the case of Overcast (1917), the painting that The New Yorker reproduces to illustrate Schjeldahl’s review, Kandinsky simply and strikingly defies anything like an accurate transfer to the page. See the original and you understand what the artist means when he speaks of creation in terms of “catastrophe,” “cacophony,” and “the music of the spheres.” See it in the magazine and much of the somber strength that bears out the title has been lost in a too-brightly-lit, almost garish translation.

Clearly then, this show, which runs through January 13, needs to be seen in person. With the Wright/Kandinsky magnet working overtime, it will be crowded. Late last Friday morning people were already lined up around the block. At the Guggenheim, however, the setting becomes part of the show; there’s art in the flow of the crowd. Look down from the great spiral on the space Wright defined as the courtyard, and the mass of people moving slowly toward the entrance becomes a painting in motion, living pointillism arrayed in a molecular mix of colors, forms, and styles. You’re seeing visitors from a world that passed for “normal” out on Fifth Avenue and 88th Street entering into what Kandinsky called “the true work of art … a mysterious, enigmatic, and mystical creation” that “acquires an autonomous life, becomes a personality, an independent subject, animated with a spiritual breath, the living subject of a real existence of being.”

Note: I found the quotations about the Guggenheim in the 1997 edition of New York 1960 (the Monacelli Press).