|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 45

|

|

Wednesday, November 10, 2010

|

We planned to drive through Scotland … in search of where my father’s beloved 39 Steps was filmed.Margaret Salinger

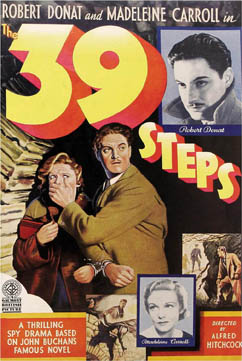

For J.D. Salinger, the high point of that drive through the land of The 39 Steps came when life and art coalesced. According to his daughter Margaret’s memoir, Dream Catcher (2000), it happened when a flock of sheep blocked the road, a real-life manifestation of the moment in Alfred Hitchcock’s movie that allowed “the hero and heroine” played by Robert Donat and Madeline Carroll “to escape, handcuffed to each other, from their captor’s car.”

Salinger’s 39 Steps tour of Scotland occurred in 1968 during the two-week trip to the U.K. he took with his children, twelve-year-old Peggy and eight-year-old Matthew. Since Salinger was 49 at the time, the quest had presumably been brewing somewhere in his consciousness for 33 years. Assuming he first saw the movie when it opened at the Roxy Theater in New York 75 years ago this September, he would have been 16, roughly the same age Holden Caulfield is when the events in The Catcher in the Rye (1951) take place.

The misguided but widespread perception that Salinger hated movies derives from Holden’s profane fulminations on Hollywood, where his brother D.B., a talented writer, went to make money. Holden also has problems with the theatre, especially the Lunts and the fawning of their fans. After suffering through the Christmas show at the Radio City Music Hall, where the Rockettes are forever “kicking their heads off,” he savagely and hilariously summarizes an unidentified Hollywood epic (“It was so putrid I couldn’t take my eyes off it”). Salinger’s own feelings on the subject come into play when Holden uses movies as a measure of the intelligence of his 10-year-old sister Phoebe: “If you take her to a lousy movie, for instance, she knows it’s a lousy movie. If you take her to a pretty good movie, she knows it’s a pretty good movie.” After mentioning her fondness for The Baker’s Wife, with Raimu (“It killed her”), he comes to her (and the author’s) favorite,” The 39 Steps, with old Robert Donat:

“She knows the whole goddam movie by heart, because I’ve taken her to see it about ten times. When old Donat comes up to this Scotch farmhouse, for instance, when he’s running away from the cops and all, Phoebe’ll say right out loud in the movie — right when the Scotch guy in the picture says it — ‘Can you eat the herring?’ She knows all the talk by heart. And when this professor in the picture, that’s really a German spy, sticks up his little finger with part of the middle joint missing, to show Robert Donat, old Phoebe beats him to it — she holds up her little finger at me in the dark, right in front of my face. She’s all right. You’d like her.”

If Holden has taken his sister to The 39 Steps even half as often as he claims, it figures to be a favorite of his, too. In other words, Salinger is giving his fixation with the movie narrative space in his first book, written some 15 years after he first saw it.

A Show Biz Family

The subject of virtually everything Salinger has written since the 1950s is the Glass family, which is headed by retired vaudeville performers Les and Bessie, whose seven children all performed through the thirties and forties on a radio show called It’s a Wise Child. According to various published glimpses of Salinger’s own family life, a notable feature of his New Hampshire retreat was the 16 mm film projector with which he screened vintage movies for the amusement of family members, lovers, friends, and the occasional total stranger. As Margaret Salinger writes, “Our shared world was not books, but rather, my father’s collection of reel-to-reel movies.” Someone visiting for the first time could be pretty sure that before the evening was over the host would offer to show The 39 Steps (or some other favorite like The Thin Man, Animal Crackers, or Lost Horizon). Is it any wonder that Salinger conceives of the Glass family saga in the same terms by having his alter ego, Buddy Glass, introduce the long story “Zooey” as “a sort of prose home movie”?

Connections

Granted, The 39 Steps is a wonderfully enjoyable movie, one of Hitchcock’s best, the crowning glory of his British period (along with another Salinger favorite, The Lady Vanishes), but of all the people who have seen and admired it, not many would make a special trip to the Scottish Highlands to search out the actual locations. On the 1968 trip with his kids, Salinger bought tickets to see Engelbert Humperdink at the London Palladium as part of the same quest. In her memorial remembrance of Salinger in The New Yorker, Lillian Ross quotes from a letter she received from him about the show, which was “awful,” but they all “sort of enjoyed it, and the main idea was to see the Palladium itself, because that’s where the last scene of The 39 Steps was set.”

As Margaret Salinger reports, the movie provided her and her father with “a secret language.” As late as her senior year of high school, she would receive a postcard “saying simply, ‘There is a man in Scotland I must meet if anything is to be done. These men act quickly, quickly’ — signed Annabella Smith, Alt-na Shelloch, Scotland.”

Annabella Smith is the mysterious woman (played by Lucie Mannheim), who latches on to the Robert Donat character, Richard Hannay, at the music hall, takes refuge in his flat, tells him of the spy ring known as the 39 Steps, and, as she dies with a knife in her back, hands him the map of Scotland on which the mastermind’s home base, Alt-na Shelloch, is circled in black.

So, how to explain this movie’s enduring hold on Salinger? The creator of the Glass family would likely enjoy the fact that the action begins in a rowdy music hall of the sort Les and Bessie Glass might have played, and that it ends at the Palladium, where Gallagher and Glass might also have appeared. Another connection Salinger might have made is with Mr. Memory, who is performing onstage in both venues employing a talent not unlike that mastered by the Glass kids on It’s a Wise Child. Ask him a question of fact and Mr. Memory can give you the answer; ask the same of any one of the Glass children featured on the show over the years and they’d do the same or at least cleverly fake it.

Invincible Naturalness

For Salinger to have been fully engaged in the events on screen, the protagonist of The 39 Steps has to be, needless to say, compelling and sympathetic. Considering the aversion to affectation of any kind expressed throughout his work, most famously by Holden’s debunking of phonies, there could hardly be a better player for the part of Richard Hannay than Robert Donat. As David Thomson writes in his Biographical Dictionary of Film, “Donat had a great quality: that he could draw us further into himself by his very modesty.” Writing about Donat’s performance in another home movie Salinger liked to show, Knight Without Armor, Graham Greene observed that “emotion when it comes has the effect of surprise, like plebian poetry.” In contrast to the glitz and glamour of stardom, Holden’s “old Robert Donat” has, in Greene’s words, an “invincible naturalness.”

Donat’s Women

First, there’s Annabella Smith, the beautiful spy Donat gives refuge to and even fixes dinner for, a cigarette in his mouth the whole time, as if he’d been born to fry kippers and serve them up to hungry females whose lives are in danger. The second woman Donat bonds with is the young wife of the crofter whose remote Highlands cottage provides him shelter (for a price) while he’s being pursued as the principal suspect in Annabella’s murder. The brief, stillborn romance between Peggy Ashcroft and Donat is one of the purest, most haunting sequences in all of Hitchcock, and Ashcroft’s presence in these scenes is so subtle and fine, you can safely assume that Salinger was as moved by her as anyone else in the world would be.

When Pamela, the third of Donat’s women, played with great charm and vitality by Madeline Carroll, fully enters the story, what had been a pure thriller with some comic touches turns into an exhilaratingly contentious romance that could justly be called England’s answer to Hollywood’s big hit of the previous year, It Happened One Night. As his daughter’s anecdote about the sheep suggests, Salinger had a special fondness for the scenes where the two handcuffed lovers are fleeing across spectacular Highlands vistas.

Apparently Salinger’s only disappointment on that mission into the heart of The 39 Steps was not being able to locate the desolate manse inhabited by the spy with the missing joint in his little finger. On a visit to Scotland years later, the sharer of the “secret language” of the film, his daughter Peggy, found “the very house, still with its lovely diamond windowpanes” and sent him photographs she took of the place and of “the little stone bridge” where Robert Donat and Madeline Carroll “hid by the stream.”

Home Movies From the Vault?

If any “prose home movies” of the Glass family in Salinger’s famous vault see the light in the next year, we’re not likely to find romantic adventures of the sort that so engaged him in The 39 Steps. But you have to wonder what it was that sent him back to this movie, again and again, vicariously handcuffed to a beautiful blonde, sharing a night’s lodging with a lovely young wife, and cooking kippers for a mystery woman who had only hours to live. One of Salinger’s female visitors in the 1980s, a dancer named Wendy Perron writing in Vanity Fair online recently (April 14) remembers seeing a note on his wall that read, “Love is a journey into the unknown.”