Chess Forum

| NEWS |

| |

| FEATURES |

| ENTERTAINMENT |

| COLUMNS |

| CONTACT US |

| HOW TO SUBMIT |

| BACK ISSUES |

Chad Lieberman

Many chess players appreciate the role of the pawn in a chess game. It provides cover for your pieces as you develop them in the opening; it can be sacrificed for an advantage in time or space in the middlegame; and it is the driving force during the endgame as it victoriously marches to its promotion.

But many don't realize that the pawn can also act in a more mysterious way. For instance, when someone leaves a pawn unprotected, the opposite player must make an incredibly important decision. If he takes the pawn, what will happen next? If he doesn't capture, can he still improve his position in other ways?

I think that many players will admit that, unless they see a concrete continuation that is losing for them upon capturing the pawn, they will snatch the pawn and hang on to their material advantage with all they've got. And why shouldn't they think this way? An extra pawn will frequently decide a game.

In this week's featured game, black's demise was brought about by a certain greediness that led him to capturing a pawn that was not his to take. Although, if you were looking over his shoulder during the game (at move 22), it would be difficult to blame him: the pawn capture immediately attacks the white queen and removes a pawn that could become very strongly stationed at e4. One must weigh these circumstances against those that occurred in the game, however.

As I'm sure you will observe when playing through this fantastic attack by white, capturing the pawn on e3 gave white just enough time to get things going, and that was all she wrote for black.

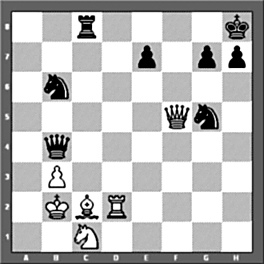

White to mate in two moves.

Link to solution at the bottom.

Vesely, J. - Cerny, J. | |

| 1.e4 | c6 |

| 2.d4 | d5 |

| 3.Nc3 | dxe4 |

| 4.Nxe4 | Nd7 |

| 5.Nf3 | Ngf6 |

| 6.Nxf6+ | Nxf6 |

| 7.Ne5 | Be6 |

| 8.c3 | g6 |

| 9.Bd3 | Bg7 |

| 10.Qe2 | Nd7 |

| 11.Bf4 | Qa5 |

| 12.Nc4 | Bxc4 |

| 13.Bxc4 | 0-0 |

| 14.Qxe7 | Nb6 |

| 15.Bb3 | Qf5 |

| 16.Be3 | Rae8 |

| 17.Qh4 | Qd3 |

| 18.Rd1 | Qb5 |

| 19.Qg4 | Bh6 |

| 20.Qe2 | Bxe3 |

| 21.fxe3 | Qg5 |

| 22.0-0 | Rxe3 |

| 23.Qf2 | Re7 |

| 24.Rde1 | Rd7 |

| 25.Re8 | Nd5 |

| 26.h4 | Qh5 |

| 27.Re5 | Qh6 |

| 28.Bxd5 | cxd5 |

| 29.Qf6 | Qg7 |

| 30.Qf3 | Rfd8 |

| 31.Rfe1 | Qf8 |

| 32.h5 | Kg7 |

| 33.g4 | Qd6 |

| 34.g5 | a6 |

| 35.h6+ | Kf8 |

| 36.Rxd5 | Qxd5 |

| 37.Qf6 | Kg8 |

| 38.Qg7# | |