|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 47

|

|

Wednesday, November 24, 2010

|

You jump on the riff and it plays you.Keith Richards

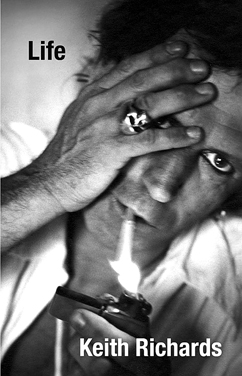

I actually thought Keith Richards might be running out of gas. He’d been cooking up a storm from page one of his magnificent Falstaffian orgy of a book, Life (Little Brown $29.99) — a farcical Arkansas drug bust; earthy, vivid glimpses of a postwar boyhood in Dickensian Dartford; listening to Radio Luxembourg “in the days before rock and roll”; fame and fortune with the Rolling Stones; life “on the border of art and villainy” in underground London; firing Brian Jones in Winnie the Pooh’s house; but when he spends five and a half pages quoting his son Marlon’s recollection of life with his drug-drenched mom, Keith’s ex, Anita Pallenberg, I began to think that even the great riff master was not immune to the curse of the celebrity bio, where the glitz gets tiresome, the glamour goes south, and readers begin squirming or yawning or rolling their eyes at the banality of life at the top, the names dropping like flies, ditto the pay-backs, and it’s like who cares, or as Keith would put it, bla bla bla boinky boinky.

Never fear. Just when you’re about to start skimming, the wild man proposes to Patti Hansen. In most celebrity bios the great moment, set in a posh Mexican hideaway, would be couched in prose that’s all warm and fuzzy, and you’d put the book aside and go listen to a Stones album. But this is Keith Richards proposing and such is his beloved’s excitement at the popping of the question that she jumps on his back, breaking his toe, which means two weeks on a crutch, which leads to this Richardsonian moment: “A few days before our wedding day, I found myself running through the Mexican desert on a crutch with a black coat and chasers on. We’d had a fight, Patti and I, some premarriage thing, I don’t know what it was about, but here I was, hobbling through cacti, chasing her into the desert, ‘Come here, you bitch!’ like Long John Silver” — so says the man who inspired Johnny Depp’s Jack Sparrow and played his father in Pirates of the Caribbean.

Decking Mick

Then you come to the first sentence of Chapter Twelve: “It was the beginning of the ’80s when Mick started to become unbearable.” Mick is, of course, Mick Jagger, front man for the Rolling Stones, who has been brilliantly and mainly admiringly portrayed, his early artistry “on display in these small venues, where there was barely space to swing a cat,” the Jagger shimmy evolving “from the fact that we used to play these very, very small stages” where if “you swung a guitar, you hit someone else in the face.” But all bets are off when Mick betrays the group ethic Keith so fervently believes in by attempting to bill them as Mick Jagger and the Rolling Stones while recording a solo album called She’s the Boss (“I’ve never listened to the thing all the way through. Who has? It’s like Mein Kampf”). Led astray by an “inflated ego” and “big ideas” in his pursuit of “musical fashion,” Mick actually begins taking singing and dancing lessons: “We know the minute he’s going plastic,” says Keith. “Charlie [Watts, the drummer] and I have been watching that ass for forty-odd years; we know when the moneymaker’s shaking and when it’s being told what to do.”

Now behold what happened in Amsterdam in late 1984. It’s 5 a.m., Mick and Keith have been out on the town, Keith has lent Mick the jacket he was married in, and Mick has ignored Keith’s warning and is on the phone to summon the stoic Charlie Watts (“Where’s my drummer?”) to his regal presence.

“About twenty minutes later, there was a knock at the door. There was Charlie Watts, Savile Row suit, perfectly dressed, tie, shaved …. I could smell the cologne! I opened the door and he didn’t even look at me, he walked straight past me, got hold of Mick and said, ‘Never call me your drummer again.’ Then he hauled him up by the lapels of my jacket and gave him a right hook. Mick fell back onto a silver platter of smoked salmon on the table and began to slide towards the open window and the canal below it. And I was thinking, this is a good one, and then I realized it was my wedding jacket. And I grabbed hold of it and caught Mick just before he slid into the Amsterdam canal.”

While the execution of the anecdote, like so much of the book, is the equivalent of a ringing cluster of riffs by Richards (the borrowed wedding jacket, Charlie’s Savile Row suit at 5 a.m., the cologne, the salmon, the canal, and, the last touch, that it’s not Mick he’s grabbing hold of but the jacket), some of the credit should go to the writer he wisely chose to share the work with, James Fox.

Bangers and Mash

Somewhere just beyond page 500, as I’m tiring of certain mannerisms (“I dearly love” so-and-so, “Willie Nelson and I are close” etc. etc.), Keith scores again with culinary tips (“cooking is a matter of patience”) and a recipe for bangers and mash, which he cooks for himself at odd hours (the recipe ends, “HP sauce, every man to his own”). Keith’s capacity for rage and violence (“a red mist in my eyes”) is sounded all through the book, usually with a jesting undercurrent. For example, there’s the unfortunate guest who made off with the spring onions Keith had been planning to add to the bangers and mash he was making the night of his daughter Angela’s wedding. Upon spying the culprit, who had put the onions behind his ears for a lark, Keith grabs a pair of sabers he keeps over the fireplace and chases him into the night. So it goes. Whether he’s playing Long John Silver or Jack Falstaff, Keith’s juices and the book’s never stop flowing, and every time you think “oh no, he’s crossed the line,” he’ll charm you by bringing out his dogs and cats, like the Russian mutt he rescued (“a cloud of fleas surrounded him”), which reminds you of his choir boy/boy scout boyhood when he used to go around with a pet mouse named Gladys housed in his pocket (“I would bring her to school and have a chat in the French lesson when it got boring”) until his mother, Doris, who “didn’t like animals,” had both Gladys and his cat “knocked off.”

The Wonderful Little World

Drugs, music, pets, friends and lovers, Life has it all, and no less potent than the anecdotal flow is the amount of musical insight displayed. If you read Keith on the subject of the ensemble dynamics, you may, as I did, hear the Stones, early and late, as you never heard them before. The beauty of the group working together is something he cherished from the start, referring to the “early days of the magic art of guitar weaving” when you “realize what you can do playing guitar with another guy and what the two of you can do is the power of ten.” He finds “something beautifully friendly and elevating about a bunch of guys playing music together,” making “this wonderful little world that is unassailable.” It’s when Mick assails the ideal of the group years later that he starts becoming “unbearable.”

Songwriting, like group togetherness, has its own “bizarre integrity.” Asking himself “what makes you want to write songs,” Keith says, “In a way you want to stretch yourself into other people’s hearts. You want to plant yourself there, or at least get a resonance, where other people become a bigger instrument than the one you’re playing.”

In many of the best-known Stones numbers — songs like “Satisfaction” and “Jumpin Jack Flash” — the words essentially articulate the riff. “When you get a riff like ‘Flash’ you get a great feeling of elation,” Keith writes, “a wicked glee.”

Rejuvenation

Something wicked is definitely going on in the latest Stones studio LP, A Bigger Bang (2005), which was recorded around the time Richards began writing his book. It’s obvious that the experience of digging back into the stuff of his story energized him. The “weaving” effect is spectacular throughout, particularly in the opening track, “Rough Justice,” which comes as close to guitar heaven as anything I’ve heard since Eric Clapton and Dwayne Allman attained nirvana together as Derek and the Dominoes. “Weaving” is too gentle a term for what’s going on here; it’s a tide, a force field, a thousand points of sound. One of the most striking features of the album is that Mick Jagger no longer seems to be fronting the group but submerged within it, voicing Keith’s riffs, at one with them, almost as if he were compensating for what Richards perceived as his sins in the 1980s. The result is a powerful album, a rejuvenation almost as triumphant as Bob Dylan’s Love and Theft and Modern Times. In the same way, what Keith Richards achieves in Life can be mentioned in the same breath with Dylan’s Chronicles Volume One and Ray Davies’s X-Ray. And not only is it one of the best rock autobiographies, it’s number one for the second week in a row on the New York Times non-fiction best-seller list.