|

|

Vol. LXIII, No. 40

|

|

Wednesday, October 7, 2009

|

|

Usually when I’m asked why I write … I reply, “To avoid a day job.” But the truth is that there are people in real life I want to honor. It’s easy to write about despair. It’s tough to present optimism realistically and appealingly. I think it’s a worthwhile goal to help people find genuine pleasure without feeling like fools.—Paul Rudnick, quoted in Time, May 3, 1993

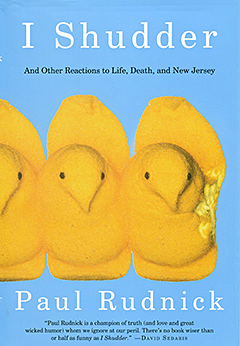

The subtitle of Paul Rudnick’s new book, I Shudder: And Other Reactions to Life, Death, and New Jersey (Harper $23.99) could as easily have ended with Life, Death, and Manhattan. If, like me, you feel that New York City is more closely and profoundly attached to New Jersey than to New York state, the combination works either way. However you style it, the New Jersey-born-and-raised author was clearly destined to live and write in the Big Apple. Quirks of behavior involving his diet and his inability to drive a car would alone be enough to qualify him for residence there. Some of the funniest moments in the book concern young Paul’s bizarre eating habits and failed driving lessons with his long-suffering father. And if you want a close-up look at one of the “mainstays” of his diet, just check out “the adorable Peeps” on the cover of I Shudder: those “acid yellow baby chicks made of marshmallow, with sooty black eyes … available in families of six or eight, attached to their siblings in a Siamese-twin fashion.”

The reference to families is apt, since Rudnick’s family is a treasure he brilliantly exploits here and in his second novel, I’ll Take It (Knopf 1989), which is to shopping as Moby Dick is to whaling. For all we know, the four Peeps wrapped around the cover and spine could represent Paul and his brother Evan, and his parents, Selma and Norman. The Four Rudnicks would make a great sitcom, a New Jersey Ozzie and Harriet that Paul may yet write one day. If he does, it’s sure to be zanier than the original. Instead of cute witty Ricky, you’d have cute, gay, witty, Peep-addicted Paul. Instead of dead-pan, wisecracking David you’d have Evan, “a passive-aggressive Che Guevara” with waist-length hair who once “wheeled his motorcycle into the living room” of the family home in Piscataway “and parked it on the wall-to-wall carpet” and then “photographed this treason.” And instead of the whim-driven, pro-active Ozzie, you’d have the genial, patient physicist Norman, an “ace diplomat” and “mathwhiz” trying to teach algebra to Paul:

“My father stared at me with Vulcan determination; he did everything but grab my hand and use his index finger to write the equations on my palm …. But he was too nice to confront me with what we both knew: ‘You are not my son! You are a hubcap!’”

Best of all, in place of Harriet, the ever-resourceful cleaner-upper of Ozzie’s fiascos, you’d have the incomparable Selma, a semi-closeted Bohemian life-force the fates have confronted with one son who parks his motorcycle in the living room and another who won’t eat “real food” and whose “sweet tooth has spread to all of [his] other organs” (“I probably have a sweet appendix”).

One thing that makes Paul Rudnick a more complicated writer than the “gifted and hilarious social observer” mentioned in the jacket copy is his ability to deal humorously, wisely, and compassionately with essential realities such as death and family, as well as the gay life and AIDS, which he took on in his play (and movie) Jeffrey. In I Shudder, he writes of losing friends “as AIDS prowled its way through Manhattan,” and, in the same chapter, he finds something amusingly beyond despair in his father’s death when he describes his brother Evan kneeling by Norman’s bedside, “gently taking his hand, and murmuring, in a low, insistent tone, ‘You can let go now. We all love you, You can let go.’” As Paul puts it, Evan “was completely well-intentioned, but after the first few attempts, it became clear that my father wasn’t following the manual, and that my brother, without meaning to in any way, was starting to sound impatient, like the Grim Reaper with a golf date.”

New Jersey Soul

In the 1993 Time profile, Paul dismisses the stereotype of the campy preening homosexual, calling the “flamboyant style of humor” that he cherishes “a form of gay soul.” The point at which gay soul and New Jersey come together in I Shudder is in his account of the 1993 Gay Rights March on Washington when he comes to the Mall, “which was filled with the AIDS quilt.”

“People were divided about the quilt,” he writes. “Some thought it was quaint and fussy, like a cemetery designed by the Ladies’ Home Journal. But on that day, the quilt was overwhelming.” After admitting that he doesn’t cry easily (“I didn’t cry at my father’s funeral, or at any of the memorials I’d been to for friends who’d died of AIDs”), he’s finally moved to tears when he sees that “someone from New Jersey had died,” someone he didn’t know, and that the panel on the quilt included a map of his home state. “The panel was made from blue and gold felt, and it looked like a team banner, hanging from the rafters of a high school gym.”

Selma

Thankfully, Selma Rudnick was able to read the book in galleys before she died last month and to realize, as if she didn’t already know it, how much of her wise good humor is at the heart of her son’s best work. While Paul’s film critic alter ego Libby Gelman-Waxner at times seems to be a comic projection of a flighty, scathingly gossipy Selma in Rudnick’s 1994 collection If You Ask Me, there’s a truer, more memorable picture of her in that paean to the delights of shopping, I’ll Take It. Watching his mother comb her hair, which “flowed almost to her waist” and had not been “trimmed since the age of twenty-one,” Joe (aka Paul) sees “the beautiful, almost swaggering girl of her black-and-white wedding photos” taken “during the early days of the war …. She had looked devastating, like Rosalind Russell as a sinuous businesswoman.”

The Wild Side

The title I Shudder actually comes from “The Most Deeply Intimate and Personal Diary of One Elyot Vionnet,” a series of first person adventures interspersed with the author’s crazed, often uproarious dealings with agents, actors, producers, and theatre people in L.A. and Manhattan. Elyot offers Rudnick a persona devoid of limits, without gatekeepers, capable of leaping the wildest impulses with a single bound. These flights of fancy are as borderline creepy as they are funny and they suggest a new direction for the playwright (I Hate Hamlet, Valhalla, among others), screenwriter (Addams Family Values, In and Out, among others), novelist (Social Disease being the first of two), and contributor of occasional pieces in the New Yorker. I Shudder shows that Paul Rudnick can not only “honor people in real life” but may one day ride the mad muse that gave him Elyot Vionnet toward the creation of a wildly funny, visionary human comedy of Manhattan — as long as he heeds his own counsel about the state next door: “Here’s what I know about New Jersey: If you’re a citizen, be proud of it. I knew a guy from Piscataway who would tell people that he was from the far more posh Princeton, which was forty-five minutes away. I always wanted to tell him, Darling, you’re still from New Jersey. Who are you kidding?”