|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 42

|

|

Wednesday, October 15, 2008

|

|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 42

|

|

Wednesday, October 15, 2008

|

|

|

If the piano is to be what it inherently is, it must be taken away from the horns, allowed to do its solo turn, like a great magician or juggler. It is not by its nature an ensemble actor but a spell-binding storyteller. It is Homeric.

— Gene Lees in “The Poet: Bill Evans”

Fifty years ago Bill Evans (1929-1980) made a record that was packaged and designed to put him on the map. It was called Everybody Digs Bill Evans (Riverside 1958/Original Jazz Classics CD1987) and featured Sam Jones on bass and Philly Joe Jones on drums, along with a cover displaying testimonials to the pianist’s talent, taste, and originality from his then-better-known peers, Miles Davis, George Shearing, Ahmad Jamal, and Julian “Cannonball” Adderley. The album landed among a stack of records for review at the offices of Down Beat, where an editor who had yet to discover Evans noticed it, took it home, listened to it, and was still listening at 4 a.m. In his nicely felt profile, “The Poet,” Gene Lees says that what stood out more than the brilliance of the playing was “the emotional content of the music,” which spoke to him “in an intensely personal way.” Lees decided to put Evans on the cover of Down Beat, and soon became a close friend.

“Peace Piece”

Of all the glories on Everybody Digs Bill Evans — whether ballads like “Lucky To Be Me” and “What Is There to Say?” or uptempo stunners like “Oleo” — ”Peace Piece” is where the music and the musician are most memorably invoking what Evans termed the “inner voices” of his “basic conception.” The six-and-a-half minutes of unaccompanied invention carrying that suitable but inadequate title (“peace” being only one aspect of the creation) take the imagination to a different place with every listening. Just now it took me, musically and emotionally, to the closing moment of Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights. With his left hand moving gently and unwaveringly back and forth from one to another of the same two chords while his right hand does the juggling, conjuring, emoting, and storytelling, Evans ventures into the same region of wonderment Chaplin discovers when the once-blind flower girl touches the hand of a tramp and realizes that this pathetic figure she’s just been patronizing is the “rich and handsome” benefactor she’d imagined to be responsible for funding the restoration of her sight. Chaplin uses music of his own composition to help put the moment over, and since it’s a silent film, the spoken words appear on the screen. For the tramp, the title says, “You can see now?”; for the girl, “Yes, I can see.” For the audience, there’s a special resonance in the language of revelation, the notion of seeing taken to the highest power. Something similar happens at the conclusion of “Peace Piece” when in the hush following the last note the music seems to ask, “You can hear now?”

Bill Evans’s respect for the integrity of “Peace Piece” was such that he preferred not to share with an audience this, next to “Waltz for Debby,” his most famous and oft-requested composition. In one sense, the rationale is in the nature of the form he’s established — the right hand’s adventures are unique, not to be repeated, each one like a chapter in a book or stanza in a poem or finished drawing, complete in itself; since the idea is to compose freely within a structure, the “piece” could never be played the same way twice, no more than it could, as mentioned, take the imagination of the listener to the same place twice. Evans’s protective attitude is simply an aspect of his compositional philosophy and his concept of jazz as an art form, which is to keep the music in the moment, an idea he rewords in the liner notes he wrote for that most celebrated of jazz albums, Kind of Blue, recorded a year later with Miles Davis. After referring to the “Japanese visual art” that forces the artist “to be spontaneous,” an art “in which erasures and changes are impossible,” he suggests that those who see the resulting pictures “will find something captured that escapes explanation” — and excites imagination.

The Man

You can see and hear just about all the incarnations of Bill Evans on YouTube. In the excerpts from a 1965 set on British television, he looks like the bespectacled square, the white-guy stereotype that encouraged reverse racism in black jazz fans when he was the only white in Miles Davis’s sextet. Lees describes him in terms of a WASP with “a smalltown America 1950s haircut” (it’s actually more like a 1930s haircut). Evans’s eager, forthcoming manner in an interview given around the same time belies the cool, closed-in surface severity. By 1972, his hair has been liberated. By 1979, he’s maned and bearded, more the Russian bear (he’s half-Slav, half-Celt) than the waspy nerd. In response to those disgruntled fans, Miles Davis famously asserted, “I don’t care if he has green hair and purple breath” or words to that effect, because, as Davis put it, “Bill had this quiet fire that I loved on piano. The way he approached it, the sound he got was like crystal notes or sparkling water cascading down from some clear waterfall.”

Not only, then, is Evans a poet and a magician, he’s a force of nature in mortal form who somehow happened to be born to a Russian mother and a Welsh father in Plainfield,N.J. According to Gene Lees, when Evans was young he was “elegantly coordinated,” played football at Southeastern Louisiana (the starting quarterback on a championship team), was a “superb driver with fine reflexes … a golfer of professional stature, and … a demon pool shark.” But in time he was also a heroin addict who had to borrow from friends to support his habit, carefully noting exactly how much he owed each person, and years later paying them back when he was making good money. Rather than accepting that his habit was evil (though he kicked it, only to get fatally hooked on cocaine), he saw it on the grand scale, life and death. “Every day you wake in pain like death,” Lees quotes him as saying, “and then you go out and score, and that is transfiguration.”

Quietly Lovely

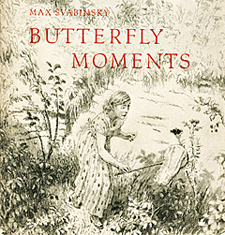

When Gene Lees cites “the springtime lilac poignancy” of Everybody Digs Bill Evans, he’s got to be thinking of “Peace Piece,” a “pastoral improvisation,” as Ted Gioia calls it, “more a mood than a composition.” The idyllic associations reflect my own experience on first hearing it. I was looking through a little book published in Prague in 1954 called Butterfly Moments that I’d picked up among the leftovers at an area library’s book sale. Not until I sat down with it did I notice the 20 water colors of butterflies scattered through the pages, the work of a Czech painter named Max Svabinsky, interspersed with an English translation of some poems. When Bill Evans’s left hand began casting its spell, I was gazing not at Svabinsky’s butterflies but at the pen and ink sketch on the cover showing a quietly lovely woman in a pretty, ankle-length dress with a butterfly net in her hand, her eyes fixed on the winged beauty she’s about to capture.

How can a woman be “quietly lovely?” Because the music makes her so, because every now and then the boundaries dissolve, sounds and images and words chiming or rhyming to make an experience that can’t be consciously set in motion but simply has to happen, as it happened to me the day the piano poetry of “Peace Piece” entered into the summer warmth of the scene and made music of this woman and her movements, bringing her to life. Here, surely, was Svabinsky’s muse, his ideal, the love of his life as invoked by Evan’s playing. Open the book and at first glance the front endpapers show nothing but the pond, dragonflies in flight, reeds bending, everything in a soft-lead-pencil haze, including the woman, who is up to her knees in the water, naked. Look at the rear endpapers and she’s back in her long-skirted dress, sprawled barefoot on the bank of the pond, dozing, hugging the grass, the net flung to one side, the air alive with butterflies as the piano creates the element of sound that inspired Miles Davis to speak of “crystal notes” and clear “cascading” water.

Butterfly Moments ends with an epilogue about the artist whose drawings are “perhaps best compared to the songs in the works of some of the great masters of symphonic music.”