|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 42

|

|

Wednesday, October 20, 2010

|

I know every book of mine by its smell, and I have but to put my nose between the pages to be reminded of all sorts of things.George Gissing

To see why books will never be replaced by hand-held devices, you need only spend time sifting through the world of donations making up this year’s Friends of the Princeton Library Book Sale. At last count, for example, there were something like six tables filled with art books of the highest quality, the majority of them from the estate of Susan Merians. While looking through a bound volume, however splendid, will never be as satisfying as seeing the original up close, it’s a more substantial experience than clicking through the virtual equivalent.

“Virtual” is the word. There’s nothing virtual about the heft of an early printing of Hemingway’s Death in the Afternoon with its Juan Gris frontispiece and bold black and white photographs. Better still, consider another treasure from this year’s sale, the magnificent three-volume 1904 Constance Garnett translation of Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace. In all my years of book sale sorting, I have never seen this, the McClure Phillips American edition, nor has a bookman as rich in rarities as Between the Cover’s Tom Congalton. No doubt the beauty of this book can be scanned and reproduced, but nothing is as good as holding the three volumes, “putting your nose between the pages,” as Gissing would have it, and admiring the proto Art Deco embellishments on the spines.

Although her translations were denigrated by various commentators, including Vladimir Nabokov and Joseph Brodsky, Constance Garnett (1861-1946) bonded well enough with Tolstoy to become, in effect, his truest English voice. It has been said, and for all purposes by Hemingway himself, that when he read Tolstoy he was reading Constance Garnett. The language of War and Peace and the other great Russian novels was for him the language of an Englishwoman who began to go blind while translating Tolstoy’s epic. In A Moveable Feast, Hemingway quotes himself in conversation remembering how many times he “tried to read War and Peace until [he] got to the Constance Garnett translation.’” And he’s in her debt again, when, in The Green Hills of Africa, he says of her translation of The Cossacks, “In it were the summer heat, the mosquitoes, the feel of the forest in the different seasons, and that river that the Tartars crossed, raiding, and I was living in that Russia again.”

Alive and Well

My translation of the message the masses of books in the Community Room at the Princeton Public Library are shouting is No in Thunder!, meaning total rejection of the notion that books are the pathetic, neglected, unloved, bygone entities pictured on the Roz Chast cover of the October 18 New Yorker. For evidence that the almighty book is alive and well, come to the library and Hinds Plaza this weekend for the Friends of the Library’s annual sale.

In the past, we had time to check practically everything packed into the boxes Chris Ducko would haul down from the storage area in the penthouse. Not this year. Never before have so many spectacular donations arrived in the months preceding opening day, Friday, October 22. It’s fitting that the biggest sale in our history not only coincides with the library’s 100th anniversary but celebrates the memory of the man who used to set up the tables and haul down the stock. Thanks to the book sale’s longtime friend Sherwood Brown and a team of Sigma Chi volunteers from the University, we were able to deal with the magnitude of the task, which was unprecedented, with floor-to-ceiling ranks of boxes extending the length of the machine room.

Signed by JCO

Besides a donation from former Senator Bill Bradley containing a number of volumes inscribed to him, the two tables filled with books from the Lewis Center of the Arts are highlighted by a dazzling array of works by Joyce Carol Oates in translations from all over the world. Some of the cover designs actually improve on the American originals. The author has signed ten of these books especially for this year’s sale, five in translation and five in English.

Smiling Faces

The aforementioned New Yorker cover will no doubt take on a life of its own as a product, an in-demand souvenir of upper middlebrow culture. The image, in case you haven’t seen it, is of a lofty array of shelves teeming with books while a young man sits in front, plugged into a laptop, apparently reading. All is not well in bookland, however. Because the reader is engrossed not in a book but a mechanism, none of the little faces sketched on the spines of those pastel volumes is smiling. Some are openly horrified, some look merely out of it, stupefied. Were the person in the picture a reasonably readerly-seeming adult who might conceivably belong to such a plenteous library, you might tell yourself that the need for contact with the “real thing” would eventually overcome the convenience of the mechanism and he, or she, or you, would take down one of the volumes, some nicely worn edition with tactile allure, a keeper, a book with a past, and muse over its pages, enjoying the texture of the cover and the aura and aroma of the associations — maybe an old lover gave it to you or maybe it kept you company when you were feeling lost or saw you through some dark night of the soul. At bedtime you can take it with you, it’s handy, companionable, relatively soft (imagine crawling under the covers with a cuddly Kindle), and when you turn on your booklight, you can think of young Abe Lincoln reading by the fireside.

Since Roz Chast’s reader appears to be a teenager, the message is clear. He’ll never appreciate the real thing. All those books are doomed to be sold or, if someone in the family has the community spirit, donated to a book sale like the one opening this Friday at the library.

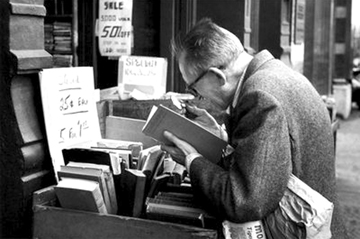

The photograph, “Fourth Avenue, New York (man reading at outdoor book stall), June 4, 1959, is from André Kertész’s book On Reading.