|

|

|

Vol. LXV, No. 37

|

Wednesday, September 14, 2011

|

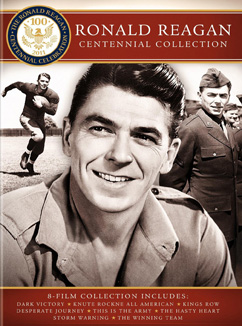

On Ronald Reagan’s Centenary: Scenes People Talked AboutStuart MitchnerYou know, in the old days he wouldn’t fly …. He always took the train, which was so much longer …. Imagine, if he didn’t change his mind about flying, he wouldn’t be where he is. — Walter Pidgeon, about President Ronald Reagan (1982) The September 7 Republican candidates debate took place, at least from some angles, virtually under the wings of Air Force One in the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. No, it’s not a replica; it’s the real thing, the same aircraft, SAM 27000, used not only by Reagan but by six other presidents, from Nixon to George W. When you think about it, Ronald Reagan’s story is so improbable, so amazing, so American Dream-run-wild, that it makes perfect sense for an airplane to occupy a permanent place in a building dedicated to a reluctant flier. According to his fellow actor Walter Pidgeon, it was only when he was traveling around the country as a spokesman for General Electric (a junket that helped lay the groundwork for his political career) that Reagan was able to bite the bullet and acclimate himself to airborne transportation. Flying was second nature of course to Brass Bancroft in Saturday matinee specials like Secret Service of the Air (1939), where Reagan played a former army air corps lieutenant who had been a commercial pilot before joining the Secret Service. In Desperate Journey (1942), one of eight films included in the Ronald Reagan Centennial Collection (Warner Home Video $59.98), he was the only American in the crew of an RAF Flying Fortress shot down over Germany. A decade later in Prisoner of War (1954), he was an army officer parachuting behind the lines to investigate rumors of brutality in a Korean POW camp. Although Desperate Journey is probably the weakest film in the Warners collection, the presence of Errol Flynn gave it some box office clout and one sequence did wonders for Reagan’s image. The scene in question has a German major played by Raymond Massey grilling Reagan in the hope that a naive Yank (“half-American, half-Jersey City,” Reagan tells him) could be manipulated into divulging useful information about the new RAF bomber engine. As the questioning goes on, Reagan is hungrily eyeing the ample breakfast, shown in a soft-focus close-up, laid out on a tray for the major. After spewing a lot of Danny Kaye-style doubletalk in lieu of information, Reagan knocks the commandant cold, helps himself to a share of that big breakfast, and saunters out of the room sipping tea. As he shows Errol Flynn the German officer crumpled under the desk, he says, cool as can be, “The Iron Fist has a glass jaw.” Those two lines (not to mention the Jersey City crack and the whole scene) were the sort that audiences talk about. Errol Flynn knew it, and did his best to get the script changed in his favor, but producer Hal Wallis had promised Reagan that the scene would be shot as scripted, and he kept his word. Saving Ginger Rogers The closest thing to a film noir in the Centennial Edition is Storm Warning (1951), which also has the distinction of being the only film ever made co-starring Ronald Reagan and Ginger Rogers (1911-1995), whose centenary is also being celebrated this year. If you know and love Ginger Rogers as the sassy dancing queen of the Great Depression and later as a charming romantic comedienne who could convincingly play teenagers when she was in her thirties, you will appreciate the sheer weirdness of Storm Warning’s opening minutes. A New York fashion model has landed late at night in a small southern town to visit her sister, played by Doris Day in her first non-singing role. Arriving by bus lugging a big suitcase, Ginger’s character spots a cab parked in front of a cozy little diner that at first looks welcoming, a neon-lit oasis in a night you begin to sense is steeped in moral darkness. When she asks about a cab, the cab driver and the owner of the diner glare at her with nothing but murder in their eyes and you’re thinking, hey, don’t you know this is Ginger Rogers? When these two brutes were growing up in the 1930s, she was probably dancing in their dreams as she charmed a nation out of the doldrums, and even at 40 she’s still got that glow. So what’s going on? The answer is the whole town’s in the clutches of the Ku Klux Klan, all except a fearless D.A. played by Ronald Reagan. When some Klansmen gun a man down later that night, Ginger gets a look at the faces of the Imperial High Wizard himself and the killer, who she soon finds out is her sister’s husband. The other scene in the film-noirization of America’s Ginger takes place at a Klan rally, where a giant cross is burning above a field full of robed, hooded Klansmen, women, and even children; one Klansman holds his hooded daughter up to give her a clearer, more instructive view of Ginger as she’s hauled into the fiery center of the scene and lashed again and again with a whip because she’s threatened to tell the world about what she saw that first night. At the sound of a siren, the D.A. to the rescue, she’s bundled out of sight. As Reagan strides through the crowd, shrugging off its taunts and threats, he recognizes certain voices and shames the owners, calling them by name. “She should be home in bed,” he says to the little girl’s father. As he comes into full view, in the light of the flaming cross, he calls out the High Wizard. It’s one of most heroic moments in his film career. In ten years he’ll be running for governor of California. He’s only 40, like Ginger, but he’s already got his presidential mojo working. He carries the day. The shamed crowd ditches their hooded robes and scatters. Meanwhile Doris Day has been shot by her own husband in the crossfire and dies in Ginger’s arms, but that doesn’t mar Reagan’s triumph. It’s 1951, McCar-thy and the communist witch-hunts are going strong, and though Reagan’s still a Democrat at this point, you have to wonder whether he was seeing the Klan as a racist, lynch-prone mob or as a reflection of the paranoia plaguing the country. Thirty years later, when Reagan was in the White House, Ginger Rogers told Barbara Walters that during lunch breaks in the filming of Storm Warning, “Ronnie would talk — guess what? — politics.” No surprise there. Reagan’s wonkish devotion to the subject was legendary and helped break up his first marriage, to Jane Wyman. Playing Politics From what I can tell, Reagan’s part as the crusading D.A. in Storm Warning was the closest he ever came to playing the real-life political role that took him to the California governor’s mansion, the White House, and a last resting place in the 243,000 square foot memorial compound in Simi, with its Air Force One pavilion. Among the 53 parts he played between 1937 and 1964, he’s been a DJ, a drunken playboy, a cynical pianist, a shy soldier, a tramp, a rancher, several cowboys, straight man to a chimpanzee, a professor, an epileptic biochemist, and, on the very cusp of his political career, a crime boss who arranges murders and belts his mistress (Angie Dickinson) in Don Siegel’s The Killers. Unless more of an effort is made to understand the implications of the projects Reagan was seriously engaged by, his Hollywood career will be little more than a colorful footnote to the history of his presidency, with attention limited to landmark portrayals of real-life figures such as George Gipp in Knute Rockne All-American and Grover Cleveland Alexander in The Winning Team. The death scene in Knute Rockne All-American in particular proved useful throughout his political life, providing him with that invaluable five-word rallying cry, “Win one for the Gipper.” An indication of what makes Reagan finally such a fascinating, devious, many-layered subject (“as strange a fellow as any of us had ever met,” according to his son Ron’s memoir, My Father at 100) is another five-word phrase uttered by Drake McHugh, the double amputee in King’s Row who wakes up to the reality of his missing legs with the cry, “Where’s the rest of me?” This was the role and the film Reagan favored above all others, the one to which he was almost obsessively attached, arranging White House showings of King’s Row to friends, colleagues, and even visiting heads of state. “Whoever would have dreamed that there would be such a script,” Sterling Hayden said in a 1981 television interview with Tom Synder, “that a second- or third-rate actor could have made such a transition? No novelist would dare make such a story.” And what novelist would choose The Killers for a future president’s last film, made on the eve of his political coming out? It’s a picture Reagan would have preferred not only to forget but to see removed from the national memory. This dark, violent piece of work was released in 1964, even as he was making speeches for presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, and around the time audiences were enjoying the deadpan black comedy of Sterling Hayden as Jack D. Ripper in Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove. No one watching Reagan’s cold, tight-lipped, relentless performance as an underworld boss, the epitome of human corruption, would call it “second-rate.” The quotes are from Doug McClelland’s Hollywood On Ronald Reagan (Faber and Faber 1983) and Tony Thomas’s The Films of Ronald Reagan: The Hollywood Years (Citadel 1980). The Centennial Collection includes Dark Victory, Knute Rockne All American, Kings Row, Desperate Journey, Irving Berlin’s This Is the Army, The Hasty Heart, Storm Warning, and The Winning Team. |