|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 37

|

|

Wednesday, September 15, 2010

|

|

|

“Jimi’s dead!” This announcement comes to us from a total stranger who knows we’ll know who he’s talking about. It’s a perfect mid-September day in London, sunny and mild, and we’re walking along the canal between Camden Town and Regents Park on our way back to a flat in West Hampstead. Our homeward route takes us down Abbey Road, a street of some significance in the summer of 1970. The Beatles may have broken up but London is still the center of the rock and roll universe, and to walk down Abbey Road past the EMI studios and the crosswalk pictured on the cover of the album of the same name still carries a charge.

The young, longhaired messenger bringing us the news tells us Jimi died here, in London, in some Kensington hotel. That’s all he knows. We don’t doubt his word; the death of Jimi Hendrix, September 18, 1970, is, sadly, no more of a surprise than was Janis Joplin’s death earlier the same year. As we walk on after taking a picture of our shadows on the dark water of the canal (one way of marking the moment), I’m thinking of the first time I heard that amazing soundscape, that wild new world of sonic wonder. Three summers before, in Michigan, in a rented house between Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti, a friend says “Listen to this.” In the summer of ’67 the Doors’ “Light My Fire” was our idea of exciting music and was being played to death on FM and even AM stations around the country. Are You Experienced made the Doors sound small and contained. You could hear mortal musicians striving. “The Jimi Hendrix Experience” said it well. Sitting there in front of a puny little portable stereo whose shabby speakers were pouring forth this complex mass of sound, it was more than an experience: it was as if some existing, hitherto impenetrable dimension had been breached and the essential nature of listening expanded. “Purple Haze all in my head.” “Let me stand next to your fire.” “Are you experienced?” No, not really. I didn’t even know what I was hearing. I didn’t know about wahwah pedals, feedback, phasing; to my virgin ears, it was an orgy of mysterious effects. Although I bought the first three albums, I listened to them sparingly. Hendrix was not something to be enjoyed casually, for pleasure, the way you would, say, “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds.” That was exhilarating; this was like war, sonic combat, pure musical adrenaline.

The only comparable moment of recognition that comes to mind is my first exposure to the fresh, fierce, new-world sound of Ornette Coleman, whose 80th birthday was March 9 of this year. The shrill audacity of that sound was so singular that it transcended context, time, and place. There was nothing remotely topical about it. Even though it seemed to herald other realms of possibility, it had nothing to do with the great events of the sixties.

Listen to Jimi Hendrix and there’s no doubt what time period you’re in. It’s all there, the whole story, the Manson murders, race riots, assassinations, Woodstock, Altamont, and above all, Vietnam. Access YouTube and listen to Hendrix play “Machine Gun” or “All Along the Watchtower” in such an ecstasy of invention as to make the accompanying combat footage from Vietnam, firestorms, explosions, tracers, napalm, falling soldiers, terrified Vietnamese, seem merely secondary.

Although Hendrix never actually served in Vietnam (he did spend a year with the 101st Airborne in the early sixties), he was very much there, as Michael Herr writes in Dispatches, recalling “a lot of fire coming from the trees, but we were all right as long as we kept down. And … suddenly I heard an electric guitar shooting right up in my ear and a mean, rapturous black voice singing [“Foxy Lady”].” Herr turns around and sees “a grinning black corporal hunched over a cassette recorder.” That was the first time he ever heard Jimi Hendrix. Referring to the soldiers in the 101st Airborne, he says, “That music meant a lot to them. I never once heard it played over the Armed Forces Radio Network.” Small wonder, considering what Jimi was saying in “Machine Gun,” lines like “Evil man make you kill me, evil man make me kill you, even though we’re only families apart” or “I pick up my axe and fight like a farmer, yeah, but you still blast me down to the ground.”

Stolen Signs

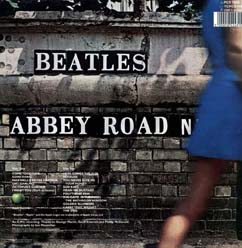

If you happened to be walking home on Abbey Road in September 1970 and didn’t know better, you might think it was just some other street in St John’s Wood that for some reason was bereft of signage. A year after the release of Abbey Road, all the signs identifying the street the album was named for had disappeared (with the possible exception of the embedded-in-stone one shown on the back cover). Those familiar white London placards had been purloined in the dead of night. The low wall in front of the studio building was, however, as yet undefiled (or unblessed) with the worshipful graffiti from pilgrim tourists my son and I saw there and took pictures of 26 years later.

Into the 1970s

It would be easy to brand 1970 as the Year the Beatles Broke Up and Went Solo, Twilight of the Gods, Death of Swinging London, and so forth. To the contrary, the 1970s saw a flowering of music across the United Kingdom and Europe. In addition to the evolving of known quantities like Led Zeppelin, there were innumerable progressive, psych, and folk psych albums by mostly short-lived groups of little or no reputation, all variously inspired or influenced by Dylan, the Beatles, the Stones, the Who, the Kinks, Cream, David Bowie, King Crimson, and Pink Floyd, to name a few, and, of course, Jimi Hendrix.

As for the Beatles, 1970 began with the ill-fated Let It Be album, an uncharacteristically lame production by Phil Spector, and ended with George Harrison’s astonishing coup, All Things Must Pass wherein Spector redeemed himself with the wall-of-sound production style that made him famous. In between, you had Paul McCartney’s one-man-band solo LP, a lyrical respite from what was happening in the spring of Cambodia and Kent State. Then came John Lennon’s first and best solo album. Even Ringo weighed in with Beaucoups of Blues, an album I had no interest in.

Here’s to Ringo

I don’t mean to sound dismissive on the subject of Richard Starkey, who turned 70 two months ago on July 7, an event that received considerable media coverage, including a New York Times editorial. Only a genius of fateful arrangements could have imagined the absolute rightness of the way Ringo’s endearingly goofy, deceptively hapless presence sets off John’s wit and passion, Paul’s virtuosity and lyricism, and George’s mystic cool. Imagine the film, A Hard Day’s Night, without Ringo. The other three Beatles all get their licks in, but Ringo is funny, human, pathetic, and lovable, a big kid playing with a little kid in the only sequence in which a single Beatle gets more than a moment of attention. For that matter, imagine Sgt. Pepper opening with anyone other than Ringo singing “With a Little Help From My Friends” in his big happy buoyant voice. As a drummer, he’s no Keith Moon or Ginger Baker, but the last thing the Beatles needed was flashy drumming. Ringo was a pro with a touch of his own and a willingness to give his mates exactly what they needed. Listen to “Strawberry Fields Forever,” or, better still, the lesser known Beatles masterpiece, “Rain,” which came out as the B side of “Paperback Writer” in June 1966. The drumming is no less amazing than the song it’s driving. Finally, there’s Ringo whaling away on “Helter Skelter,” the ultimate Beatles freak-out. That’s Ringo, not John, who screams “I’ve got blisters on me fingers!” as the monster finally chugs to a halt. It’s hard to hear “Helter Skelter” without feeling that it’s caught up in the friendly fire aftershock of Jimi Hendrix’s expansion of musical dimensions a year earlier in Are You Experienced.