|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 39

|

|

Wednesday, September 26, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 39

|

|

Wednesday, September 26, 2007

|

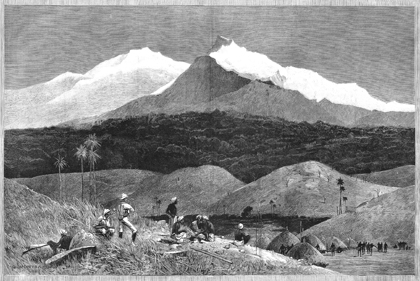

THE MOUNTAINS OF THE MOON: The headliners of the exhibit now on view in the main exhibition gallery of Firestone Library are shown here in an image taken from the supplement to the Illustrated London News from February 1, 1890, which notes that the mountains were “Discovered by Mr. H.M. Stanley’s expedition.” Located in Uganda, they are now officially and less romantically referred to as the Ruwenzori range. “To the Mountains of the Moon: Mapping African Exploration, 1541–1880” is not to be missed. It will be open through October 21. Hours: Monday to Friday, 9 to 5, Wednesday 9 to 8, Saturday, 12 to 5, Sunday, 12 to 5. The handsome 84-page exhibition catalog ($20) is fully illustrated in color, with numerous full-page images of historic maps, and a foldout timeline of African exploration. For information, call (609) 258-3184.

|

AFRICA FIRST: Sebastian Münster’s (1489-1552) woodcut map, with added color, “Totius Africæ tabula, & descriptio universalis, etiam ultra Ptolemæi limites extensa” is taken from his “Cosmographia universalis” (Basel, 1554). The earliest obtainable map of the whole continent of Africa, it can be seen in “To the Mountains of the Moon: Mapping African Exploration, 1541–1880,” a fascinating exhibit that will be at Princeton University’s Firestone Library through October 21.

|

The adventure now contained inside the first floor exhibition room at Princeton University’s Firestone Library is there to be enjoyed and explored for only three more weeks. Curated by John Delaney, “To the Mountains of the Moon: Mapping African Exploration, 1541–1880” is a fascinating show. Don’t miss it. You have until October 21.

According to the curator, the concept was inspired by, among other things, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness whose narrator prefaces his account with some words about a boyhood “passion for maps” that had him looking “for hours at South America, or Africa, or Australia” and losing himself “in all the glories of exploration.” What intrigued Conrad was actually more subtle than “darkness,” as is suggested in another reference to his youthful “map-gazing” in Geography and Some Explorers, a piece privately printed in 1924 that serves as an introduction to the exhibit. It wasn’t the “dull, imaginary wonders of the dark ages” that attracted him but the “exciting spaces of white paper” where he could imagine “worthy, adventurous, and devoted men … sometimes swallowed up by the mystery their hearts were so persistently set on unveiling.”

The map from 1766 facing you as you enter the room is “Mr. Bolton’s Africa, Performed by the Sr. Danville Under the Patronage of the Duke of Orleans.” The idea of the map as theatre, with the explorers as actors and the cartographers as directors, is taken up by Mr. Delaney in the exhibition catalogue (also available online), where “performances of exploration and discovery” would “entertain and enthrall European audiences and inspire and embolden their governments.”

One of my favorite performances is Sebastian Münster’s (1489-1552) woodcut map, with added color, from his book, Cosmographia universalis (Basel, 1554). The earliest obtainable map of the entire continent, it looks as free and easy as the work of an inspired child compared to the delicately detailed graphics of later, more sophisticated maps. To illustrate the general location of Cameroon you have a naked, pudgy, harmless-looking white cyclops, meant to signify the mythical Monoculi tribe. An elephant with impressive tusks is grazing in the extreme south. The illustrated mountain ranges resemble little loaves of bread or twisted coils of rope, the seas are sinuous and sprightly, and the streams and lakes growing out of the bread loaves representing the Mountains of the Moon appear to be the long legs of two headless giraffe-like creatures whose necks join to become the Nile. Kingdoms are indicated by cartoon crowns and sceptres; the birds perched on limbs are half as big as the trees; and you almost expect to see Dr. Dolittle and Chee Chee leaning over the railing of the little ship on its way around the Cape of Good Hope.

That intrepid explorer of the dark continent, Dr. Dolittle, is even more in evidence in another Münster performance, a woodcut map without color from a 1522 edition of Ptolemy’s Geographia, again with the thin, spindly legs that seem to grow out of the Montes Lunae, this time with three lakes where the creature’s bellies would be. If you think I’m hallucinating, check out the drawing of the pushmi-pullyu (“the rarest animal of all”) heading the Tenth Chapter of Hugh Lofting’s The Story of Doctor Dolittle. While I’m regressing, I might as well admit that my tour through this exhibit also sent me back to Peter and Nancy in Africa and the days when schoolbus rides could seem like exotic voyages that demanded the making up of stories illustrated by wildly imaginary maps, usually improvised on the shape of one’s home state. The beauty of fourth-grade geography was in applying odd shapes to reality and coloring them in and then dreaming of “far-off lands” with magical names like Tucumcari and Waco and Walla Walla. One of the joys of the Firestone show is in the names. As if the Mountains of the Moon aren’t enough, you have Timbuctoo and the Mountains of Kong, a fictional range that cartographers passed off for real on almost all 19th-century maps of Africa until a French expedition in 1887-1889 proved otherwise.

Timbuctoo! There’s all the poetry of geography in one name. Vicarious explorers and road-dreamers like myself would travel long and hard to get to a place called Timbuctoo, expecting maybe fabulous medinas and secret passages when the aspect of the place is, as the exhibit shows, less than thrilling. But would you slog through thousands of miles to get to the place if it were called, say, Stanleyville or Leopoldville?

As I beheld various cartographic performances of Abyssinia it was exciting to realize that the Mountains of the Moon were in the vicinity of the landscape said to have inspired Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s haunting, opium-dream fragment, “Kubla Khan.” Exploring the subliminal origins of Coleridge’s poetry in The Road to Xanadu, John Livingston Lowes (a man born to explore with a middle name like that) found numerous sources and echoes in James Bruce’s Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile (referenced here in Bruce’s corner of the exhibit). Known as “the poet of African travel,” Bruce was widely read in Coleridge’s day, and there is evidence that the author of “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” actually meant to write about the seek-ing of the fountains of the Nile. The key passages from Bruce that Lowes focuses on contain words and images echoed in “Kubla Khan,” including “romantic situ-ations,” “magnificent cedars,” “enchanted water,” and a prodigious cave. What better example of the “audience” for these performances than the omniverous Coleridge, whose map-gazing helped launch two of the greatest literary voyages ever undertaken.

As Lowes zeroed in on the origins of Xanadu and that Abyssinian maid “singing of Mt. Abora,” he was at the same time following Bruce’s quest for the origins of the Nile. A reference to “the cliff of Geesh” jumped out at me because one of the most striking images in “The Mountains of the Moon” is Pasquale Scaturro’s photograph from 2003 of the spring at Gish Abay, where the Blue Nile begins. Seen from a distance on the wall of the exhibition room, it has the look of a Franz Kline or some mixed-media creation on the delusional nature of romance, an idea the catalogue description does little to contradict. After all this exploration and cartographic imagery devised to fill those “exciting spaces of white paper,” the great, mysterious Nile that nourished whole civilizations is traced to “a reedy marsh bound by a rock-andwood fence and funneled through a rusted half-inch-in-diameter metal pipe into a little stone house.”

The Actors

As you might expect, the featured performers in “The Mountains of the Moon” are those “worthy, adventurous, and devoted men” the exhibition is dedicated to, the explorers who set foot on the reality the cartographers attempted to depict, notably Henry Stanley (1841-1904), David Livingstone (1813-1873), and Richard Burton (1821-1890), each represented by photographs, documents, anecdotes, and books. The journalist/explorer Stanley, whose name was given to the highest peak of the Ruwenzori range (as the Mountains of the Moon are now known), displayed his flair for drama in a letter from Zanzibar (Nov 11th 1874) to his American publisher (the original document is on display along with a printed version), which begins: “I am almost choked with my emotions today — for I must sit down & write to ever so many people my Farewell. You fellows in New York with many years of brightness & joyous life in store, & I with a prospect of death by violence, or a lingering fever.” As it turned out, he lived on for three decades while the editor he was writing to died five years after he got the letter.

Other featured players include Mungo Park (1771-1806), René Caillié (1799-1838), John Speke (1827-1864), and Heinrich Barth (1821-1865) who was, according to the catalogue, “one of the European superstars of African travel and exploration” and spent five years disguised as a Muslim scholar “ranging widely and freely over northern, central, and western Africa.”

The exhibit Web site is in some ways even better than being in the room since it permits you to roam over the maps up close and enjoy a better view of the annotations and other details. It can be accessed on the Web at http://libweb5.princeton.edu/visual_materials/maps/websites/africa/titlepage.html.