|

|

|

|

Vol. LXV, No. 39

|

Wednesday, September 28, 2011

|

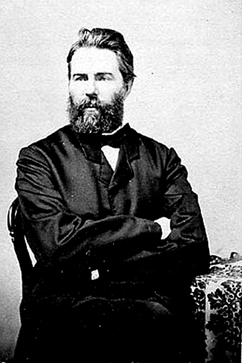

Melville Walking: Before and After September 28, 1891Stuart MitchnerHis tall, stalwart figure, until recently, could be seen almost daily tramping through the Fort George district or Central Park, his roving inclination leading him to obtain as much outdoor life as possible. — New York Tribune,October 1, 1891 When the happy day arrives in which you set your feet upon the Path and begin your pilgrimage, the world will know nothing of it; earth no longer understands you; you no longer understand each other … your destiny is a secret between yourself and God. — from a passage in Balzac’s Seraphita underlined by Herman Melville in 1890 My predilection for picturing Herman Melville (1819-1891) walking the streets of New York probably began with the opening chapter of Moby Dick where Ishmael invokes “your insular city of the Manhattoes, belted round by wharves” and surrounded by commerce, whose “streets take you waterward” to the “extreme downtown” of the Battery and “from thence by Whitehall, northward.” The word that sets everything in motion begins the third paragraph: “Circumambulate the city of a dreamy Sabbath afternoon.” Now close your eyes and imagine the author of that sentence circumambulating a timeless dream of Manhattan. It’s not Ishmael you see walking, however, and it’s not the heroic figure who personified adventure and romance and manliness to Nathaniel Hawthorne’s young son Julian in that golden time when Hawthorne and Shakespeare were helping feed the fire that became Moby Dick. Nor is the nightwalker the same word-drunk 32-year-old who finished his masterpiece in a stifling Fourth Avenue room in the summer of 1851, and who, a year later, put the city itself vividly into play in his next book, Pierre. No, this brooding Manhattanite venturing up and down Broadway and back and forth on 23rd Street, down to Gramercy Park, and sometimes all the way up to Central Park, is the man who lived the last 28 years of his life at 104 East 26th Street, near Madison Square, where he died at 72 on September 28, 1891, 120 years ago to the day. It’s the aging, forgotten Melville I visualize making his rounds, usually at dusk or after dark, unless he’s accompanied by one or the other of his little granddaughters Frances and Eleanor. The wonder is that this same grandfather walking city streets in the late 1880s is pondering novelistic issues for the first time in almost 40 years. The product of his meditations will send a shockwave through a literary world in which he has consigned himself to obscurity. But Billy Budd won’t see the light until 1924, three decades after his death, when the discovery of an unfinished manuscript kept in a Japanned tin bread box launches the Melville revival. All the while harboring his secret project, Melville would browse in secondhand bookshops, purchasing nautical prints, a set of Balzac, and Schopenhauer’s Studies in Pessimism. A young clerk in one Nassau Street bookshop remembers him as a person of “generosity and gentleness” walking with “a rapid stride and almost sprightly gait.” This then is the same musing septuagenarian who once took his four-year-old granddaughter Frances for a walk in Madison Square Park and then forgot all about her, so deep was he in his musings, only to rush back “in terrified haste to meet her coming home by herself.” His eldest granddaughter Eleanor, who grew up to become the keeper of his books and papers and the bread box from which Billy Budd would be rescued and published and hailed as a masterpiece, recalled the walks they took together: “Setting forth on a bright spring afternoon for a trip to Central Park, the Mecca of most of our pilgrimages, he made a brave and striking figure as he walked erect, head thrown back, cane in hand, inconspicuously dressed in a dark blue suit and a soft black felt hat.” Imagine the writer plotting the fate of his “illiterate nightingale” Billy as he walks side by side with nine-year-old Eleanor, who breaks loose when they reach the park, “running down the hills, head back, skirts flying in the wind.” Imagine the somber author smiling at the scene in spite of himself. Eleanor was not yet ten when her grandfather died, and of all the biographers who will continue to explore Melville’s life and work, only she had “been there,” only she had knowledge of his room (“a place of mystery and awe”) with the “small black iron bed” he died in, and only she could know how it was “to climb on his knee” to hear “wild tales of cannibals and tropic isles” when “part of the fun” was to put her hands “in his thick beard and squeeze it hard. It was no soft silken beard, but tight curled like the horse hair breaking out of old upholstered chairs, firm and wiry to the grasp, and squarely chopped.” Riding the Elevated Since my night thoughts of Melville walking respect neither time nor space, I can also see him striding along the High Line, pacing the top deck of the good ship Manhattan, casting his eye over the rooftops of Chelsea. He’s been up there before, a block to the east, riding the Ninth Avenue El to his job as a customs inspector on the West Street docks and, in later years, the Third Avenue line, after he was assigned to an East River pier uptown. The advantage of blurring the borders of time and space is that it allows my fantasized Melville to look north from the back window of 104 West 26th and see the Empire State Building 40 years before it was built and beyond it the skyscrapers of midtown. The obvious downside of this double vision occurs when he stands on the rooftop of his building staring south at the massive northward surging white cloud ten thousand times deadlier than any conceivable white whale, as the twin towers fall. And who more likely to be gifted with the power to view such things than the man, who in the euphoria of having wrestled with Moby Dick and survived (“I have written a wicked book and feel spotless as a lamb”) boasts to Hawthorne, “Leviathan is not the biggest fish — I have seen Krakens.” Madison Square One day sitting on a bench in Madison Square at dusk facing the chronically windy junction of Broadway, Fifth Avenue and 23rd Street, Melville sees the oddly shaped mass of the as yet unbuilt Flatiron Building rising above the staggered vista of billboards — Fifth Avenue Bath, Windsor Hotel, Swift’s Specific, Seabury & Johnson’s Mustard Plasters — atop the ticket office for the Erie Railway. With a prow 20 stories high, it’s like Doré’s drawing of the monstrous ship Coleridge conceived for the Ancient Mariner. What a city of wonders lies ahead, he’s thinking, if it contains structures such as this. With the converging forces of the wind closing in on the spectral edifice, Melville decides to test his mettle. This is a younger man now, circa 1876, one who feels there might be excellent therapy in some buffeting about. He has the city to himself, not another soul on the street as he heaves his way into the vortex holding his hat with one hand and righting himself against the gale with the other. Out of the wind he comes, still securing his hat as he makes his way back to the shadowy confines of Madison Square, where the torch-bearing arm of the Statue of Liberty has been installed to publicize the need for contributions toward the casting of the rest of the statue. The severed arm of Liberty is giving off a greenish glow, a vague humid mist tasting of sea-salt and copper. As he walks through the park toward 26th Street, Melville is thinking back 20 years to that last talk with Hawthorne prior to his voyage East, after which his late lamented friend had confided to his journal that “Melville seems much overshadowed.” The street is dead quiet. Everyone else in the world is asleep as Melville recalls his walks in the great cities of the Orient, the haunted, labyrinthine ways of Constantinople and Cairo. At home, he lingers in the front hall and looks up at a colored engraving of the Bay of Naples. It’s much as his granddaughter Eleanor will describe it some 75 years later, the blue of the bay “dotted with tiny white sails” that her grandfather would point to with his cane, saying, “See the little boats sailing hither and thither.” “Funny words,” the child thought, “at the same time a little awed by something far away in the tone of voice.” In addition to Eleanor Melville Metcalf’s Herman Melville: Cycle and Epicycle (1953) and some online sources, I consulted Andrew Delbanco’s Melville: His World and Work (reviewed in Town Topics, Oct. 19, 2005) and Jay Leyda’s The Melville Log (1951). |