|

|

Vol. LXIII, No. 39

|

|

Wednesday, September 30, 2009

|

|

It’s just not done, you know, writing in books, especially not in ink, in big bold flowing script. For one thing, if you’re organizing a second-hand book sale for the library, you can’t ask as much for a book where the fly-leaf contains an inscription — unless it’s from the author. Of course if it’s annotated by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, whose marginalia fills a shelf full of fat volumes published by Princeton University Press, you hit the jackpot; take it to the nearest auction house.

Certain dealers might not agree that personal history found between the pages of a book counts for something, no matter who’s wielding the pen. But the annotator in question happens to be a very special person, someone with a deep and dedicated interest in art, dance, World War Two, the Civil Rights movement, human rights in general, African American literature, Russian literature, horse racing, trains, you name it. This is someone who lived in her books, confided her thoughts to them, frankly and sometimes passionately. In her own way, she was blogging before there was an internet. It may be a one-sided conversation, but as you sift through the wonders of this legacy donated to the library by Geraldine Boone’s heirs, it’s clear that she was not just talking to herself. Though her impulse may have been to share these moments with her husband or her children and their children, or with some ideal soulmate, she’s also addressing you and me and anyone in the indeterminate zone called, for lack of a better word, posterity. In this era of Kindle and e-books, that sounds more like a bonus than a defect.

The upcoming Friends of the Princeton Public Library book sale is offering a wealth of extraordinary books this year from the libraries of the cognitive psychologist George Armitage Miller, who oversaw the development of WordNet; novelist, translator, and man of letters Edmund Keeley; and Pulitzer-prize-winning historian James McPherson. While we’ve managed to confine those microcosms of great libraries to self-contained units, there was simply too much Geraldine Boone to restrict to one or two or three tables. So, she’s everywhere. And her message is everywhere. The message is idealistic, moral, playful, witty, compassionate, and liberal in the best sense of the word; it also sheds some glory on Bennington, where Geraldine Babcock was a student during the Second World War.

A portion of the story that unfolds as you browse through the Boone donation is a romance played out in the gift of books to and from husband and wife. This is most visible, though discreetly (initials and a heart, every book a valentine), among the art books, which represent the mother lode of that subject area at the sale. Rowan Boone (who, by the way, was once president of the Friends) inscribed a cookbook thus: “For Geraldine, an artist in the kitchen, from her fat, pampered adoring husband.”

In fact, Geraldine’s most succinct inscription (“Yummm”) is in a cookbook.

Flying Her Flags

About once or twice a year I’d head out to Greenhouse Drive to pick up a donation and there it would be, the flag of the day flying from the flag pole in Geraldine’s front yard; it might be Sweden, or Norway, or some mute inglorious little country whose national colors I didn’t recognize. But it was never the same. For a time, certain flags were not welcome. The German flag, for instance, which she decided to fly only after corresponding with a German officer who was part of the resistance against Hitler. She loved Russian literature (as the literature table at the sale demonstrates), but she refused to fly the Russian flag until the Cold War was over.

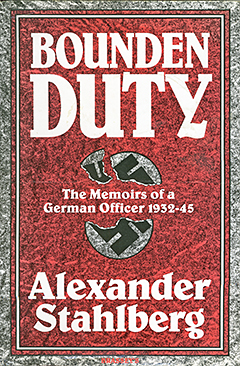

Writing on the flyleaf of Alexander Stahlberg’s Bounden Duty: The Memoirs of a German Officer 1932-45 (1990), she explains how she sent a letter to the author after reading the book: “I am overcome with amazement that he would write to me. I bought a (West) German flag because the burden of my fury at all Germans had been lifted.” In the back of the book she writes that the flag “is on my pole as I write (22 April ’93) — It’s for the brave peope Stahlberg wrote about.” Among several items attached to her copy of Bounden Duty is a note from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, of which she was a charter member.

As you learn from her jottings (and from the eulogy given by her son John at her funeral last fall), her feelings “for the underdog” were roused when she was part of the March on Washington in 1963 (an event she mentions on the fly leafs of several of her books). Martin Luther King gave her a sense of urgency for the cause of racial equality and social justice. She brought people into her home: a man just released from prison, a woman from Mississippi who came north seeking a new life. There were others, invited in and housed over the years, because she thought she could make a difference in their lives.

Snowdrops for Solzhenitsyn

Geraldine’s inscriptions show that she also had a sense of humor. According to John Boone, while she hated television, she loved “I Love Lucy,” and identified with Lucille Ball’s ditzy character: “She was interested in word games, double entendres, misunderstandings, and put downs,” says John, who added that she liked to share her sense of humor with others. “But if I were to say something funnier than she did, she would say to me, ‘Get in your box, John.’”

She also loved the cartoons in the New Yorker and would regularly think up her own cartoons and captions. One notebook for “Favorite Recipes” actually contains several pages of her “recipes” for cartoons, along with a few sketches, for she was an inveterate doodler.

Of course if you want to make a difference, there are more important things to do, like tutoring a Haitian in English, visiting prisoners in jail, or taking in Foster Children to help out families with serious problems. She also provided funding for soccer fields in South African towns.

So he wouldn’t feel homesick, she once sent snowdrops anonymously to one of her heroes, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, when he lived in exile in Vermont.

Wartime

Possibly the most thoroughly represented area of her interest at the sale is the Second World War. Geraldine was a college student during the war years but she felt a certain kinship with the war effort through the many soldiers she wrote to as pen pals and the ones she danced with at New York and Washington parties.

Her interest in Nazi prisoner of war camps and the British aviators who escaped from them led her to write to an RAF pilot named Peter Tunstall, who had escaped from more German prisons (most famously from Colditz) than anyone. She had a long correspondence and weekly telephone conversations with Tunstall that lasted over twenty years. The effects of this special friendship are scattered through a number of books on that subject.

You Want More?

What else then? She helped organize the Princeton Association for Human Rights, The Youth Employment Service, The Princeton Study Center, and the Child Placement Review Board for abused and neglected children. She was also active with the Juvenile Conference Center during the 60s and 70s.

And in her spare time, she was a talented French cook (witness the cook book section at the sale), listened to classical music, loved French Impressionist painting and the opera and ballet, did the New York Times Crossword Puzzle daily, and wrote short stories resembling morality plays.

When asked what she did professionally at her last doctor’s exam, she said she “worked for social justice and racial equality.” As John Boone put it, “At the end of the day, it was always her intention to make a positive and effective contribution, to make things better for someone or some institution. She wanted to be the one who made the crucial difference.”

One thing for sure: she’s made the crucial difference in this year’s Friends of the Princeton Public Library Book Sale, which begins with a preview this Friday at noon. For details, see the story in this week’s issue.