|

|

Vol. LXIII, No. 13

|

|

Wednesday, April 1, 2009

|

|

As a devoted customer of John Socia’s Old York Book Shop in New Brunswick ever since since its opening in 1968, I should have known about Princeton’s Bryn Mawr Book Sale long before I wandered into it for the first time on April 28, 1976. I must have heard about it from John himself, but then how is it that the most generous of book dealers neglected to inform me that one of the greatest used book events on the East Coast took place every year a mere 15 miles south of Easton Avenue?

To this day, I can’t remember who, if anyone, pushed me in the direction of the sale, which was then held behind Borough Hall in the building that has since become the Suzanne Patterson Center. I only know that I had been sitting in the Colonial Diner on Witherspoon (which burned down later that year) madly in love with the world because my first (and only) child had been born that morning. Maybe I floated over there or was escorted by a honor guard of Lamaze leprechauns. All I know is I had little interest in books as I wandered through the sale grinning like the winner of the ultimate lottery. All I came out with, in fact, was a piece of sheet music for the song “Hindustan” featuring a design of minarets, temple spires, and an elephant, all in silhouette.

Having been to maybe 30 Bryn Mawr blow-outs since that one, I should qualify as a veteran of the happy crusades by now. In those days the sale had a holy grail mystique created by early bird dealers who used to stake out a claim to their place in an outdoor line anywhere from 24 to 36 hours before the Bryn Mawr volunteers began handing out the officially numbered preview tickets for the “real line.” Something about those chilly, misty, sometimes freezing or rainy early mornings could turn decent, civilized, peace-loving people into righteous literary commandoes. As the troops of dealers, book hawks, and obsessed renegade bibliophiles assembled for the charge, the atmosphere crackled with a kind of competitive camaraderie. Great finds of the past were discussed. Some folks in the line were nervously gregarious while others stared at the ground, wound tight and ready to spring the instant the the gates were flung open at 10 a.m.

During that wild first hour when the tables are being attacked and pillaged, camaraderie is blown to the wind, tunnel vision tension is the norm, and while actual fights rarely if ever break out, it can get sticky when two obsessives knock elbows grabbing for the same book.

Last week there were hints that the economic state of the nation had altered the dynamic. On that same opening morning, the New York Times was reporting that one of the great mainstays of the trade, Powell’s Books in Portland, had taken a huge hit from the downturn (sales falling, no recovery in sight). The quest for items that would fly on ebay had obviously intensified. Amateurs and neophyte dealers were scouring the array of volumes with little sensors for the instant processing of ISBN numbers that would presumably tell them which books to pull and which to let be. Real dealers have no need and no time for online guidance. Only diehard biblioromantics like myself could have seen the book-dense vistas in that spacious arena as evidence of the survival of the species in the era of Google and Kindle. Here was the tangible reality, masses of sheer book stuff, but when I got a closer look at what was actually arrayed on the tables, I had to face up to what I knew, being a vicarious bookshop owner, both as a writer and as director of the Friends of the Library sale, that the majority of these tattered and redundant rejects and refugees (including, as almost happened, my own novel about a secondhand New Jersey bookshop) were doomed to land in dumpsters and landfills.

Doorways in the Labyrinth

Never mind the gloom and doom. I was having fun. The beauty of Bryn Mawr is the sheer chaotic extent of the phenomenon. It’s the book equivalent of the bazaar at Fez or Marrakech. It may have the appearance of arrangement — they even tried alphabetizing certain subject areas — but sweet disorder is the order of the day, especially once the crowd storms the tables.

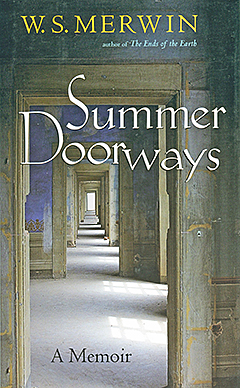

To appreciate the happy possibilities alive in this wealth of raw material, consider my first find. The day before the sale someone called me up at Town Topics to make sure I knew about the Princeton chapters in poet and Princeton graduate W.S Merwin’s memoir, Summer Doorways (Shoemaker Hoard 2005). I’d never heard of the book and had planned to look for it at the library. Now here it was, a shiny new face beaming at me from the poetry table, that halfway house of demigods and nobodies, knights of the realm and homeless waifs. And how great to find a book full of Princeton lore (poets Merwin and Galway Kinnell waiting tables in eating clubs and hanging out at the Parnassus Bookshop in “a house along Nassau Street”), not to mention the brilliant cover, with those Uffizi doorways like entrances opening into an infinitude of book sales.

Battered Treasures

Finding Merwin woke me up to the fact that I had a book column to write and needed something more interesting than mere bargains for subject matter. Almost as soon as the idea came into my head, I found a battered volume by John Buchan published in 1936, the same year that saw Alfred Hitchcock’s memorable version of Buchan’s best-known work, The Thirty-Nine Steps. The book was The Man from the Norlands (Houghton Mifflin), and had no value in its present state, being shorn of its jacket, with remnants of tape at the top and bottom of the spine, which was cocked and frayed.

According to abe.com, while the top price a good copy goes for online is $275, the original English edition, titled The Island of Sheep, is worth over $2000. Googling deeper, I found that the book originally came out in 1920, that Buchan, a Scotsman, eventually moved to Canada, where he died after suffering a stroke, and (here comes another coincidence) that not even an operation performed by the great brain surgeon and Princeton graduate, Wilder Penfield, had been able to save him.

When I opened the cover (it was priced at 50 cents), I saw a bookplate from the Isabella McCosh Infirmary that read, “In Memory of John Howell Westcott III, Class of 1918, Killed in Battle in France, September 29, 1918.” Under the inscription was a quote from Milton’s Samson Agonistes: “Nothing is here for Tears.”

Talk about Princeton echoes. Thinking of how I’d driven down Westcott Road that same morning, I read the novel’s first sentence: “I have never believed, as some people do, in omens and forewarnings, for the dramatic things in my life have generally come upon me as suddenly as a tropical thunder-storm.”

A classic opening. Thus do books speak for us, giving us captions for every thought, every mood, as did the last line of the same paragraph: “That was what happened to me on an October evening when I got into the train at Victoria.”

Think of it — there are still trains like that in England, trains you get into, where each compartment had its own little door to be opened the way you open a book and settle down for a long journey, if you get into the right book.

“Declined by Collector’s Corner”

The above message was on a card inside a volume printed by E.H. Butler and Company in Philadelphia in 1845. Collector’s Corner is the self-contained space where the BMW sale keeps its rarities. This one, Hart’s Class Book of Poetry, had been denied a place in that exclusive company and was priced at $1, no doubt because the front cover was detached and the spine was a bit frazzled. Not to worry. Decrepitude can be beautiful. Compiled by John S. Hart, principal of the Philadelphia High School, this wisely selective little anthology had a name and date written in brown ink on the title page (“Lizzie Shipp, June 18, 1858”) and under that the words “school almost out” and under that “June 21st 1861 examination next week.” Everyone has their own notions of value; that’s what makes book sales fun. But how do you put a value on this notation left by someone taking an exam two months after the beginning of the Civil War? With so venerable a book, the flaws become precious in themselves. Even the crumbling spine, the foxed and stained endpapers and the occasional penciled annotations inside become rare and strange, so that mere markings make an accompaniment to choice passages from Chaucer and Shakespeare, and Milton, Dryden, and Byron, among a sometimes unlikely assortment of others, including those illustrious nobodies Falconer, Opie, Pollock, Montgomery, Halleck, and that old favorite, Anonymous. It’s not unlike the assortment you’ll find languishing every year on the poetry tables.

My last act at this year’s Bryn Mawr-Wellesley Book Sale, was the rescuing of a homeless soul abandoned on the table of local authors, a novel called Rosamund’s Vision about a secondhand bookshop run by a book dealer very like my old friend John Socia of Old York Books, which closed some 20 years ago. John Socia died in 2001.