|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 31

|

|

Wednesday, August 4, 2010

|

|

|

|

DREAMING OF A NEW WORLD: Lewis Hines’s photograph of a sleepy young Slovak woman at Ellis Island is among those accompanying the large-scale photographic studies by Stephen Wilkes in “Ellis Island: Ghosts of Freedom,” which opened Saturday at the James A Michener Art Museum.

|

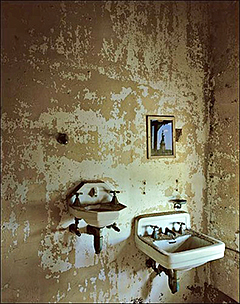

TUBERCULOSIS WARD, STATUE OF LIBERTY, ISLAND 3: Of this image from his exhibit “Ellis Island: Ghosts of Freedom,” Stephen Wilkes writes: “At a precise point, about 5 feet 2 inches off the ground, I saw the Statue of Liberty reflected in the mirror. I suddenly imagined a petite Eastern European woman rising out of her bed every morning. Seeing that reflection would be the closest she would ever come to freedom.” The exhibit will be at the James A Michener Art Museum in Doylestown, Pa., through October 10.

|

I truly felt that it wasn’t I who took a lot of these pictures. They were given to me.Stephen Wilkes

The Ellis Island dining room was a hundred feet long, and I undertook to depict along one of the long walls the role of the immigrant in the development of America.Edward Laning

“What began as a one-hour editorial assignment became a five-year passion,” says Stephen Wilkes, whose exhibit, “Ellis Island: Ghosts of Freedom,” opened Saturday at the James A. Michener Art Museum in Doylestown. Wilkes’s large-scale photographs of the derelict interiors of the hospital complex on Ellis Island, taken between 1998 and 2003, will be on view until October 10 along with vintage portraits of immigrants by Lewis Hines.

Edward Laning’s WPA-funded mural for the main dining hall was unveiled in 1937, its theme the role of the immigrant in the industrial development of America. Like the interiors photographed by Wilkes, Laning’s mural was destined for ruin. The deterioration that began with damage from a leaky roof during a rainstorm in the 1950s was followed by vandalism and neglect after the closing of Ellis Island in 1957. Although there is no mention of the Laning mural in “Ghosts of Freedom,” the visual documentation of its fate — great folds of imagery hanging like shrouds from the tattered, peeling, discolored wall — would have complemented Wilkes’s vision of abandonment and waste. In the early 1970s, surviving sections of Laning’s mural were restored and reinstalled in the Federal Courthouse in Brooklyn (a detail from it is included on page 16), and this spring a full-scale replica by an artist working from photographs in the Ellis Island Museum and Library of Congress has been touring Nevada and other western states as “The Lost Mural.”

Wilkes’s subject was not in the main building where Laning installed his immense work but in the so-called “dark side” of Ellis Island to the south where immigrants were held before being sent back to their countries of origin for various reasons, including health (TB, contagious diseases), mental illness, or suspect background. What the photographer discovered in the intricately devastated rooms and corridors of the hospital complex so fascinated him that he became, as he puts it, “obsessed. I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t erase the buildings from my mind. So I went back, many times, every chance I could …. I was blessed to be able to study every season. I photographed every corner, every crevice, in every imaginable light.”

The results are best seen in person. As stunning as they are online, the representations at www.ellisislandghosts.com can’t possibly replicate the experience of standing before something as fiercely brilliant, for example, as Isolation Ward, Recreation Room, Window Study. On fire with color and light in a no-man’s land between art and accident, the poetry of the image mocks the mundane title. No wonder, then, that the photographer sometimes plays the poet in his attempt to find words worthy of his own discoveries, thus “the radiator explodes into a dazzling pattern” and “the calm, soft water” that can be seen through the window provides “an amazing contrast to the red-lit room.”

The Artist’s Presence

While Wilkes clearly wants to project “the palpable presence of humanity,” what is more truly felt here is the presence of the photographer himself, not that of the people who passed through these rooms. With allusions to the teasing views of the Statue of Liberty outside the windows or reflected in mirrors on the ravaged walls, Wilkes promotes the message of his title, that freedom was an apparition haunting the immigrants who, after enduring a long, rough ocean crossing, found themselves confined in this halfway house on the verge of the promised land. Still, the images themselves are hardly testaments to the triumph of the human spirit; if anything, the human spirit was imperiled, drained, beaten down in these vacant rooms with their decaying, peeling walls; so, even as he points to a lone chair or table as evidence of humanity’s presence, going so far as to, in one instance, anthropomorphize a piece of furniture (“The dresser didn’t feel like a dresser. It felt like an old man sitting on a stool crouched over”), the photographer is undermined by the very brilliance of his art, the choices he made, the scenes he set using the abstract, impersonal imagery created by time and weather and neglect.

Strangely enough, given such compelling evidence of Wilkes’s aesthetic judgment, he disavows responsibility, declaring that he “didn’t take these pictures,” that this strange music simply passed through the Aeolian harp of his camera, “given” to him, brought from him to the viewer, for he applied “no light” of his own, “nor any artifice of the photographic craft.” Except of course that he spent hours and sometimes days pondering, selecting, waiting for the most propitious moment, as he implies in his caption for the flame-bright image of the wall in the Isolation Ward where “the last 30 seconds of sunlight” set the fire that blazed through an innocuous surface.

Beauty’s Underside

The caption for Blue Room With Bed Frame, one of the most disturbingly beautiful images in “Ghosts of Freedom,” alludes to painted art: “Here, in the ruins of the psychiatric hospital, I thought of van Gogh.” Like much of Wilkes’s imagery, the mottled pastels in Blue Room suggest a problematic beauty, one burdened by a darker meaning, the way references to art in the context of the fall of the Twin Towers or the luminous afterglow of an atomic explosion become subject to moral scrutiny. Such art-for-art’s-sake liabilities may not diminish the aesthetic force, but they do complicate the viewer’s response. That Wilkes is aware of this issue is implicit when, in introducing the work, he asserts that he “wasn’t interested simply in graphics born from the patina of ruin.”

These images of bleak abandoned spaces in the context of forced confinement reminded me of my visit to the Michener exhibit of Michael Kenna’s stark black and white photographs, “Impossible to Forget: The Nazi Camps Fifty Years After” (reviewed in Town Topics, February 16, 2005). Just as Wilkes pursued the ghosts of Ellis Island, Kenna photographed the ghostly remains of the death camps. It’s hard to dismiss the grim association when you see the photographs of chairs piled in a heap in the Measles Ward, or the lone suitcase in an empty room, or the prep room in the morgue, or, most particularly, the powerhouse boiler which recalls the images of ovens in the Nazi Camp exhibit. Wilkes hints at the association in his caption, when he observes that “the ancient furnace felt more like a crematorium than a boiler room.”

The Real Thing

If you’re hard put to imagine the “palpable human presence” in Wilkes’s work, you can see the real thing in the room devoted to Lewis Hines’s photos from 1905. Here are smiling Russian and Hungarian mothers laden with babies and children; an Italian family group with a father who could double for Charlie Chaplin in The Immigrant; and most evocative of all, the headscarfed young Slovak wife (judging from the ring on her finger) slumped asleep on her massive bundle. The people in Hines’s photographs are presumably the lucky ones who did not get shunted off into the hospital, TB, or isolation wards but were able to go on to take part in the making of America.

It’s quite possible that some of Edward Laning’s depictions of “real people” in his mural were based on the ones in Hines’s photographs. One day perhaps the Ellis Island Museum will have room for both the restored portions of Laning’s vision of the immigrant presence and Wilkes’s photographs of spaces haunted by it. Both works had the government’s blessing. Some 70 years after the WPA paid for Laning’s mural (the artist himself received the princely sum of $21 a week), Wilkes and the Landmarks Conservancy put together a video that eventually convinced Congress to provide a six million dollar grant for the preservation of the buildings whose ruin is depicted in these photographs. As Wilkes notes, the “triumph was not without irony,” for once the repairs were made and the “encroachments of nature” removed, “the place will never again look as it does in these photographs.”

“Ellis Island: Ghosts of Freedom” will be in the Michener’s Fred Beans Gallery through October 10. Next door in the Paton|Smith|Della Penna-Fernberger Galleries through September 5 is a refreshing second act in the form of “Icons of Costume: Hollywood’s Golden Era and Beyond.” The museum is located at 138 S. Pine St., in Doylestown, Pa. For information on films and talks related to the exhibition, call (215) 340-9800, or visit: www.michenerartmuseum.org. Though the quotes from Stephen Wilkes were taken from the website www.ellisisland ghosts.com, they originated in the lavishly illustrated book of the same name, which is available in the Museum Shop.