|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 31

|

|

Wednesday, August 4, 2010

|

|

|

A hot Saturday night in Princeton. Time to get out of the house and go to the movies. The plan is to see The Kids Are All Right at the Garden, but it’s already sold out half an hour before show time, so we land at Montgomery, where the only option by the time we arrive is Mademoiselle Chambon. My wife says it got good reviews. In fact, it turns out to be one of the most subtly acted and directed love stories this side of David Lean’s Brief Encounter (1945) and Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise (1995).

In Mademoiselle Chambon, which was directed by Stéphane Brizé, a happily married working-class man (Vincent Lindon) is asked by his young son’s tall, slender, delicately attractive teacher (Sandrine Kiberlain) to talk to the class and answer questions about what he does for a living. He’s a builder, so he talks about building houses. As the teacher stands off to one side watching him, she looks troubled, even shaken, as if the man were awakening some strange, wholly unexpected emotion in her. When he comes to her home one day to repair a window frame and finds out that she’s a violinist, he asks her to play something, which she does, but shyly, with her back turned to him. The builder responds to the short, simple, wrenchingly poignant piece much as the teacher did when she watched him with the class. He’s transfixed, mystified, overcome. For him it’s more than falling in love; it’s a revelation.

The subsequent development of the relationship is so agonizingly circumspect and restrained that some in the audience may lose patience with the love-dazed pair. Not once are they able to exchange words of love or to even begin to give voice to what’s happening to them. That language is going to be a problem is signaled in the first scene when neither the builder nor his wife can help their son with a question of grammar (“What’s a direct object?”) in one of Mme. Chambon’s assignments. There’s a certain ironic resonance in the terminology, considering how indirectly the teacher and the builder deal with the problem of their feelings for one another. The love scenes, such as they are, might be taking place in a silent film with powerful musical accompaniment. Their first embrace is a beautiful moment, gentle, tender, more prayerful than passionate, and, thankfully, nothing is said. Words only create confusion and distress, as happens when the time comes for them to take the affair on to another more committed level.

True Chemistry

That silent love scene in Mademoiselle Chambon reminded me of the extraordinary sequence in Before Sunrise where Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke share a moment in a Vienna record store listening booth. Like the builder and the teacher sitting side by side sharing music prior to a first embrace in Mademoiselle Chambon, Celine and Jessie are shoulder to shoulder listening to a folk singer singing a love song. Nothing is said, no caresses are exchanged. The couple is facing us and only we can see the depth of the attraction betrayed by the loving glances flashing from one to the other, which, of course, is how they want it. Neither is ready to risk making the eye contact that would likely lead to a first kiss (which comes in the next scene, in the ferris wheel at the Prater). For all the talking these two do in this famously conversational film, the counterpoint created by those furtive, adoring gazes makes this moment the most eloquent in the movie.

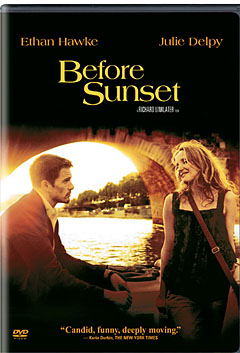

One reason Before Sunrise and its 2004 sequel Before Sunset have attracted such a devoted following is, to put it simply, because everything in both films is so true to life (life as it should be, anyway). The chemistry of attraction has rarely been as convincingly and extensively articulated. These two films are so unique as to require a category unto themselves. Ethan Hawke said as much when describing Before Sunset in a May 2009 interview in The Guardian: “It’s its own form of cinema, it’s its own entity…. it’s all about nuance…. There’s no beginning, middle and end, it’s completely fluid, just chasing the nuance of life, and kind of believing whatever God is lives in this kind of energy that flows between all of us.” In another, earlier Guardian interview, Hawke quotes Richard Linklater to the effect that Before Sunrise is about “what it’s like to connect with another human being. And how, when you actually connect with another human being, it feels like a miracle.”

Any and every summer, and any other season for that matter, generations of Celines and Jesses have met and will meet on trains, busses, autostopping, in class rooms and waiting rooms. In some elemental journeys-end-in-lovers-meeting sense, this is how it is. Though it beggars reason that girls as lovely and intelligent as the one played by Julie Delpy come along all that often, the American played by Ethan Hawke at least feels more familiar, closer to a type, a bit of a wise guy, maybe a little too smart for his own good but disarmingly earnest and thoughtful, alternately cynical, brash, and vulnerable as he casts his line at the vision of loveliness that is Celine. It’s fine that Jesse is almost laughably self-conscious at times (“I think he was a puppy in the first film,” Delpy told an interviewer). It’s the young boy in him that moves Celine, as when he tells her of making rainbows at age three with the garden hose and seeing an image of his dead grandmother in the mist. That may be a tale he’s told in the past to woo other girls, but by the time you realize how much Celine likes him, it doesn’t matter because you’re so thoroughly charmed by her that you’d trust her judgment about anything. She may have been fooled in the past (as she eventually admits during their night walking around Vienna), but this is a person whose sensitivity to “the nuance of life” is such that she can tell Jesse, using the third person, that she “likes to feel his eyes on her when she looks away.”

It’s Julie Delpy’s Celine who engineers the seduction of the audience. Whatever your age or gender, she’s the one you want to make the trip with, the one you follow when she changes seats on the train and settles down opposite Jesse. In both films, she’s the poet and the poetry while Hawke comes off as the freeform philosopher. Delpy’s presence illuminates the whole enterprise, as her co-star suggests in a 2005 Guardian interview after the release of Before Sunset: “What I love about Celine, what I felt really proud about that script, is that she’s really a fully dimensional woman. It’s very rare in movies that you don’t see a male projection of a fantasy woman…. I feel proud of the collaboration that created that character. Her work in that movie is my favorite thing about it.”

There will surely be a third and final chapter in the story of Celine and Jesse. Usually only blockbusters can swing the money for a sequel. Before Sunrise did well at the box office, but what funded Before Sunset was the first film’s achievement of classic stature, thanks to the many people who love it and have gone on to spread the word, and thanks as well to the passion for the project felt by people in the original production, notably the stars and the director who still don’t seem ready to bid farewell to these two characters. If you doubt that another sequel is looming, take a look at the ending moments of Before Sunset, with the reunited couple in Celine’s apartment. In the first film they had an afternoon, evening, and night together. A planned reunion in Vienna never came about (he showed up, she did not). In Sunset, which takes place nine years later in “real time,” they have less than 80 minutes before Jesse has to catch a plane. The car taking him to the airport is downstairs. Celine is making tea and Nina Simone is on the stereo when Celine begins talking about the time she saw the singer perform in person. Inspired by the memory, and perhaps by some womanly awareness that this move will settle the question of Jesse’s fate once and for all, she begins to do an impromptu and adorable (no other word will do) impersonation of Simone as a beaming, hopelessly enchanted Jesse looks on. Sashaying back and forth, the way the singer did at the concert she saw, she points her finger at the audience, playing to the crowd, jiving, doing Nina’s voice, “Oh yeah, baby, you’re cute,” and pinning a look on Jesse, still using the Nina Simone voice, she croons, “Baby, you are going to miss that plane.” Not taking his eyes off her, Jesse says, “I know.”