|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 32

|

|

Wednesday, August 8, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 32

|

|

Wednesday, August 8, 2007

|

|

|

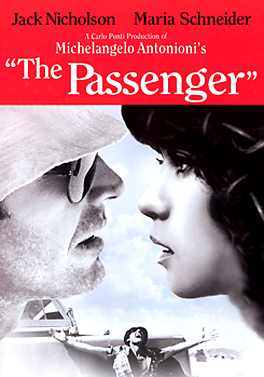

Ingmar Bergman and Michaelangelo Antonioni, who died within hours of one another a little over a week ago, made motion pictures that have the power to haunt your life. One day you think, “I’ve been here before,” and you realize, “Something like this happened in Bergman.” Or maybe you find yourself staying at a third-world hotel you’re sure you’ve seen somewhere, and then you remember the sinister North African flea bag where Jack Nicholson assumes a dead man’s identity in Antonioni’s The Passenger (1975). Pictures like Bergman’s Wild Strawberries (1957) and The Magician (1958) and Antonioni’s L’Avventura (1960) invaded the minds of a generation. College students whose heads were already swimming in Dostovesky and Kafka found themselves theorizing and arguing no less passionately about Bergman’s gothic metaphysics and Antonioni’s enigmatic aesthetics.

Audacity

As I remember, no one ever doubted Bergman’s prowess as a filmmaker, but, perhaps partly because L’Avventura had been booed at Cannes, much of the back and forth about Antonioni had to do with whether he was a genius or a talented charlatan filming glorified Shaggy Dog stories. Critics and audiences stereotyped him by stressing terms like “alienation” and “spiritual malaise.” For me, his most striking quality is his audacity. It’s a cliché to say that all the best directors make films about making films, but Antonioni takes sheer process to fabulous extremes. At once anarchist and architect, masterbuilder and deconstructionist, he lets you see him constructing his imaginary world, and then, at the expense of such things as plot and sequence and probability, he takes it all apart, abstracts it, or simply blows it to bits. Depending on your point of view, these violations of cinematic decorum may seem brilliantly daring or merely excessive. In his 1988 autobiography, The Magic Lantern, Bergman reckons that Antonioni ultimately “expired, suffocated by his own tediousness.” You can understand why Bergman would lose patience with Antonioni when he declares, on the same page, practically in the same breath, that “all forms of improvisation are alien to me” and that filmmaking is “an illusion planned in detail.”

In fact, Antonioni could be as meticulous a planner as Bergman, until he was moved to challenge himself. Think of the ten-plus minutes of pure wordless cinema that conclude L’Eclisse (1962) or the monumental stop-time explosion of the material world that ends Zabriskie Point (1969), or, probably the most memorable sequence he ever filmed, the last ten minutes of The Passenger. That film, one of his masterpieces, puts into play the idea of the audience not only willingly manipulated and taken in by the viewing experience, but followed, inhabited, and haunted by it. Like a movie-goer looking to escape into the vicarious excitement of a film, David Locke, the character played by Jack Nicholson, effectively assumes a role in someone else’s movie when he steals the identity of a dead gunrunner named Robertson. Even cynics or nonbelievers tempted to dismiss the concluding sequence as a species of directorial showing off would be lying if they said they weren’t impressed. It goes without saying that the Locke/Robertson character is alienated — he begins on the edge of the world and never looks back — but that’s only to be expected when this director conceives of the actor (according to Nicholson himself) as “a moving space.” The end of The Passenger, with Locke/Robertson waiting for death to claim him, is all about moving in space, as the camera defies the laws of reality, pushes through a building as if it were transparent, and slowly swings round to the “moving space” that is the character’s dead body. In the course of that sweeping sequence, all contained in a single incredible take, we hear the shot that kills him. The DVD of the film, available at the Princeton Public Library, offers a commentary by Jack Nicholson that is almost as good as sitting side by side with someone who was “there” and doesn’t mind confiding to you the secret of how that virtuoso ending was achieved. According to Nicholson, when Antonioni was asked to explain why so elaborate a piece of invention and engineering had been necessary, he replied, “I just didn’t want to film a death scene.”

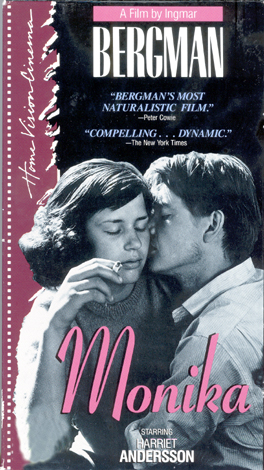

Amazing Monika

Back in the days when few people outside Sweden had heard of Ingmar Bergman, a callow midwestern youth walked into a West 42nd Street moviehouse called the Apollo to see a foreign film called Summer With Monika. The posters and lobby cards for the film, retitled Monika: The Story of a Bad Girl for the American market, promised a Nude Scene. Anyone lured into the Apollo by the prospect of seeing Harriet Andersson naked had a long wait and disappointment in store since all that was shown was a brief shot of her from behind.

The callow youth, however, was not disappointed; he was entranced, from the first atmospheric shots of Stockholm to the last moving close-up of the Swedish youth, played by Lars Ekborg, who loves, enjoys, fights for, suffers with, and marries the Bad Girl and is left at the end with a baby and not much else. Anyone who automatically associates Bergman with the austere works like Persona (1966) and The Silence (1963) should find Summer With Monika, which came out in 1952, a revelation. The funky working-class environment suggests a Swedish Mike Leigh. But the mood, photography, and cinematograpy are of a higher order and suggest that Bergman had been moved by Italian neo-realist films. Such issues as style and genre, however, are overwhelmed by the life-force voluptuously embodied by Harriet Andersson, who creates in her every move all the vicarious erotic excitement any susceptible young man could hope for. When she does her skinny-dip, she’s no less fascinating than she is when she’s smoking, drinking, flirting, dancing, crying at a movie love scene, stealing a roast, hammering a bully with a saucepan, or ducking her head from the blows dealt by her drunken father. To say that the impressionable midwestern youth was infatuated would be a gross understatement. Who cares if she’s wild and wilful and born to break hearts? There’s no resisting her. She has it all: a sensuality both womanly and girlish, extraordinarily strong features, a generous mouth, classic facial architecture, and a beautiful figure.

It’s no news that directors fall in love with their actresses. It happens with Antonioni and Monica Vitti in L’Avventura and it happens with Bergman and Harriet Anders-son, though some accounts say that their romance had moved from physical to professional by the time Monika was made. Still, Bergman offers one shot that stands as a directorial tribute, a close-up radiant with acclamation and love. Shown as she’s about to cheat on her sweet, dutiful, loving husband, it’s the first close-up that reveals just how richly, complexly attractive this actress is — in case maybe you’ve been distracted by her behavior in a role where she’s made to look grubby, silly, cheap, unkempt, almost ugly, sometimes nearly unrecognizable. Bergman’s lingering portrait acclaims the beauty and depth of her performance even as it depicts her character’s wretchedness. Writing in 1958, Jean Luc Godard called it “the saddest shot in the history of cinema.”

The Taormina Episode

My ultimate “I’ve been here before” moment came during an unusually cold early spring in Taormina, when the Danish countess who owned a pensione I was staying at invited me to a cocktail party at her villa. It began in the courtyard as I was somewhat nervously approaching the entrance (the youth was less callow, but still pretty wet behind the ears: it was my first cocktail party). A group of people had arrived just behind me. They were speaking a foreign language, but not Italian. As soon as I realized they were speaking Swedish I experienced my movie déjà vu, flashing back to Bergman’s The Magician and the moment when the coach carrying the title character and his weird party arrives at the house where they will amuse, seduce, and terrify the inhabitants. Inside the villa, I found myself talking to a Swedish fellow who looked vaguely familiar. When I told him of my flashback, he was greatly amused. “Believe it or not,” Lars Ekborg said, “I was the coachman in that scene!”

I spent the rest of the evening hearing what it was like to make movies with Ingmar Bergman. And after a drink, it didn’t even seem all that miraculous that I was at a party in Sicily with Swedish actors who had been in his films (I also met Stig Järrel, who played Satan in The Devil’s Eye ), or that I was having a long conversation about life and art with someone I’d seen making love to “Monika” on the screen at the Apollo on West 42nd Street.

Nothing like that ever happened again, though I did once sit a few rows behind Orson Welles during a performance of Turandot at the Baths of Caracalla in Rome.

This is more a video than a DVD review because both The Magician and Summer With Monika are unfortunately available only on VHS tapes; both can be found at Premier Video. Criterion DVDs of other works by both directors are available at the Princeton Public Library.