|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 33

|

|

Wednesday, August 13, 2008

|

|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 33

|

|

Wednesday, August 13, 2008

|

|

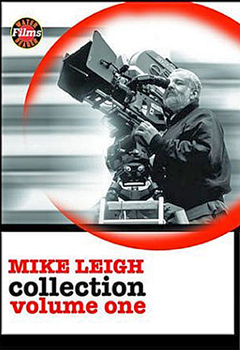

“Hitchcock famously said that the kind of woman who spends all day washing up and doing the housework does not want to go to the cinema to see a film about someone who spends all day washing up and doing the housework. And Hitchcock, on this thing and many others, was a million miles from the truth. He didn’t know what he was talking about.”—Mike Leigh, interviewed by Derek Malcolm

Of course it helps if the film about the woman doing housework is directed by Mike Leigh, who turned 65 in February. It also helps if you have some familiarity with the characters and situations his unscripted improvisations on English life illuminate. If you’ve ever lived in England, you know that it takes a form of creative chemistry as subtly nuanced and outrageously broad as Leigh’s to cover the extremes of a society that can inspire anglophobia even among anglophiles. After a year and a half of dotty bluehaired grannies, obsequious landlords out of Dickens, clueless shop clerks, and twistedly officious “public servants,” not to mention certain regional accents that seem charming early on and have you holding your ears by the time you board the plane home, you’re not sorry to be back in that other madhouse, the good old U.S.A.

The rub is that in the early films of Mike Leigh the same off-putting British reality comes across so well, is “lived” so convincingly, that you end up feeling irrational surges of affection for some of the very things that drove you nuts when you were living in old Blighty. Like for instance how cold it was one winter during the miner’s strike when the power was systematically interrupted and left you shivering for hours in a flat that was chilly enough even when the power was on, there being nothing for heat but one of those little electric hearths and something called Cozy Wrap that was supposed to pass for insulation.

Even if you’ve never lived in the land that gave us Cozy Wrap, even if what you know of England doesn’t go much beyond the Royal Family, Monty Python, Absolutely Fabulous, and the Kinks’ “Dead End Street” (“There’s a crack up in the ceiling/and the kitchen sink is leaking”), you should have no trouble relating to what Mike Leigh has accomplished in works like Hard Labour (1973), The Kiss of Death (1977), and Abigail’s Party (1977), all of which were originally made for the BBC’s Play for Today and are available at the Princeton Public Library. Be warned, though; the accents are so thick that you may occasionally long for subtitles.

Hard Labour is haunted by the bleak, stoic face of Mrs. Thornley (Liz Smith), a face you may immediately associate with the dreariest aspects of English life, even though it could just as easily be the face of a worn-down housewife in Appalachia. If there’s a story behind that rigid, unsmiling countenance, it’s not one you want to know. And yet of course you do because from the moment you enter the Thornley kitchen, the milieu has the pure, true-to-life ambience created by Mike Leigh’s preference for having his actors work without a script; everything is improvised according to a concept devised by Leigh, who has compared the filmmaking process to “a journey of discovery about what the film is” and who sees “all art” as “a synthesis of improvisation and order.”

Human Spirit

In a conversation with Mike Leigh on the Criterion DVD of Leigh’s 1993 masterpiece, Naked, novelist Will Self suggests that the director’s way of working constitutes something like an art form in itself. Self also suggests that Leigh is dealing with “fundamental episodes of the human spirit.” Hard Labour is one such episode. Mrs. Thornly earns a pittance as a maid, has a peevish husband, a lost, hapless, daughter, and somehow manages to keep the family fed, clothed, and functioning nonetheless. She never complains and never smiles, though she comes close to it when helping a sari-clad young woman figure out how to use a washing machine in a laundrette. The priest who hears her confession at the end of the film grimaces and sighs (so does the audience) because her only sin is that she doesn’t love her husband.

Discomfort

Mike Leigh’s films often make you squirm. He has a way of putting his characters into situations where ridicule sometimes violates humanity, as happens with Aubrey, the doomed amateur restauranteur played almost too effectively by Timothy Spall in Life is Sweet (1991), the first Leigh film I ever saw. You can’t help laughing at the spectacle of Aubrey lolling miserably about on the floor of his doomed French restaurant, Regret Rien, but it’s not comfortable laughter, and it touches on the problem Leigh may have in mind when he says that he sometimes finds it “quite surprising and shocking when people laugh at things [in the films] which I never thought were funny — sometimes people laugh uproariously at something which I think is rather sad and tragic.” In another online statement, he observes that “people laugh for a variety of reasons — with, or at, or out of embarrassment, or nervousness even. It’s not always a function of mirth.”

A mirthless, nervous laugh becomes a significant expression of emotional and social confusion in Kiss of Death, which contains scenes that are truly painful to watch. Trevor (played by David Threlfall) is a socially benighted teenager who seems to have no control over his foolish giggle and ghoulish grin. As his gum-chewing wouldbe girl friend waits to be kissed during an agonizingly protracted and yet brilliant scene, he cackles in her face, and when he finally kisses her well enough that she wants to take him upstairs, he grins his creepy grin and retreats. What redeems the do-I-laugh-or-groan aspect of Trevor’s awkwardness is the way he rises to the occasion after a neighbor’s ailing mother faints on the stairs. That Trevor handles the situation sensibly and humanely would seem wholly improbable were it not for the fact that we’ve seen him doing his job as an undertaker’s assistant where his duties involve washing dead bodies. Again, out of the most unlikely and uncomfortable material, Leigh and his actors create the chemistry Will Self had in mind when he spoke of “fundamental episodes of the human spirit.”

Absolutely Abigail

The human spirit has pretty much gone missing in Leigh’s thoroughly cringe-inducing Abigail’s Party, which the reviewer for Channel 4 in the U.K. termed “the most painful hundred minutes in British comedy-drama.” This nightmare of “wasted lives” and “vacuous life-styles” (as Leigh puts it in his DVD conversation with Self) definitely bears out the director’s claim that laughter isn’t always a function of mirth. While you may notice hints of the ruder and more literate nastiness of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, the strained civility of Abigail’s Party makes for a more excruciating experience, mostly thanks to Beverly, the hostess from hell. Alison Steadman’s larger than life performance — a drink in one hand a cigarette in the other — evokes the full-tilt comic flamboyance of Joanna Lumley’s Patsy and Jennifer Saunders’s Edwina in Absolutely Fabulous, which captivated TV audiences on both sides of the Atlantic in the 1990s. There’s reason to believe that Abigail’s Party influenced the concept behind Ab Fab or at least paved the way for the landmark series.

Saying the Unsayable

Nothing in Leigh’s early work quite prepares you for the sheer vehemence and savagery of Naked, which exposes the ravaged underbelly of civilization no less vividly now than it did when it came out 15 years ago. It’s hard to believe this movie was made before rather than after September 11. It’s also hard to believe that David Thewlis’s unforgettable performance as Johnny was shaped without benefit of a script. Nothing I know of in contemporary cinema can match the word-drunk genius exploding out of this crazed, driven, Orphic being’s virtuoso rave-ups that, as Will Self puts it in his conversation with Leigh, “say the unsayable about modern culture.” Like an inspired jazz musician or the most enlightened of rappers, Thewlis improvises whole cadenzas on the cosmic wretchedness of existence. His body English suggests a stylishly tortured cross between a bird of prey with broken wings and a werewolf with St. Vitus’ Dance (in fact, Thewlis goes on to play Remus Lupin in the Harry Potter movies). Naked’s concluding shot shows him limping and hopping down the middle of the street. Instead of walking into the sunset like Chaplin, he’s careening drunkenly toward the camera, which gradually leaves him behind — leaving him, in effect, to his fate.

Johnny’s adventures in London’s city of dreadful night make Naked one of the definitive films of its era. The sexual viciousness that roused the wrath of feminists is admittedly hard to take and I still wish Leigh could have done without the loathsome Jeremy (Greg Cruttwell), the well-heeled Dirk-Bogarde clone whose motiveless malignity makes Johnny’s cruelest actions seem at least humanly forgivable — which may be the main reason Leigh inflicts this sadistic predator on his film. Special Features on the Criterion DVD include The Short and Curlies (1982), a short film by Leigh starring Thewlis; the fascinating, extended conversation between the director and Will Self I’ve been quoting from; an appreciation by director Neil LaBute; and a revealing commentary by Leigh, Thewlis, and his co-star, the late Katrin Cartlidge. The commentary is of particular interest because of the insights it offers into Mike Leigh’s improvisational approach to filming.

Coming August 31

One of the greatest Hollywood films is finally coming to Turner Classic Movies. Frank Borzage’s rarely seen “Man’s Castle” will be shown on TCM (Channel 86) on August 31 at 11:30 p.m. as part of a day-long celebration of Spencer Tracy, who is at his very best in what is arguably the strongest performance of his career. As far as I know, this wonderful movie hasn’t been on television locally since 1991.